Steady state is a cornerstone concept in clinical pharmacokinetics. It connects dose, dosing interval, and patient-specific clearance to the drug concentrations that drive therapeutic and adverse effects. Yet, “steady state” is often misunderstood or oversimplified. This chapter explains what steady state is (and is not), how it arises under different dosing schemes, how to calculate and predict steady-state concentrations, and how to apply these ideas to individualized dosing and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). We highlight linear versus nonlinear behavior, infusion versus intermittent dosing, accumulation, fluctuation, loading doses, and special scenarios such as long-acting formulations, critical illness, and altered protein binding.

Key takeaways

Definition

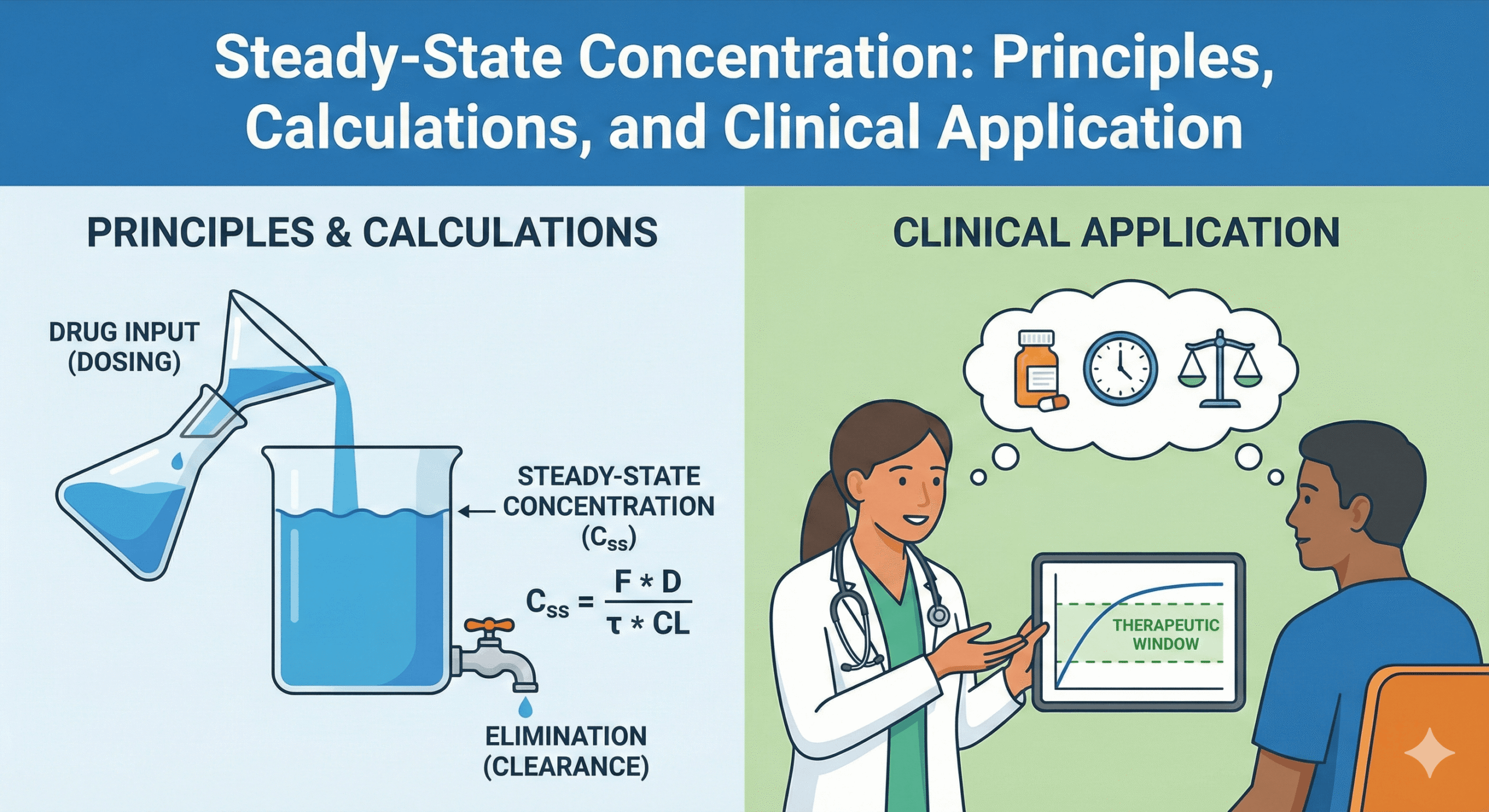

Steady state exists when, under time-invariant conditions, the concentration–time profile repeats identically during each dosing interval. Fundamentally, this means drug input equals drug elimination over each cycle [1–3].

Mathematical Formulas (Linear Kinetics)

For linear kinetics, the average steady-state concentration (Css,avg) depends only on the dose rate and clearance (CL).

Css,avg = (F × Dose) / (τ × CL) Continuous Infusion:

Css = R0 / CL

Key Kinetic Principles

- Time to Steady State: This is determined solely by the elimination half-life (t1/2), not the dose. It takes approximately 4–5 half-lives to approach >90–97% of steady state [1–3].

- Accumulation and Fluctuation: These are governed by the relationship between the dosing interval (τ) and the half-life. A longer τ typically increases peak–trough variation [1,3,4].

- Nonlinear Kinetics: Factors such as saturation or autoinduction (time-varying kinetics) will shift the steady state, invalidating simple linear predictions [1,2].

Clinical Application

- Sampling: When using concentration targets, samples should be drawn at or near steady state.

- Protein Binding: Consider unbound drug concentrations if protein binding is altered (e.g., hypoalbuminemia) [3,5].