Routes of drug administration are critical in determining a medication’s therapeutic effectiveness, safety profile, and patient adherence. Different routes allow clinicians to optimize how quickly and extensively an active compound reaches its intended site of action, while also accommodating specific disease conditions and patient factors. While numerous administration routes exist—ranging from oral ingestion to specialized parenteral injections—each route offers distinct advantages and disadvantages depending on factors such as drug chemistry, the urgency of treatment, and patient compliance. In this comprehensive guide, we will extensively discuss enteral (oral, sublingual, buccal, and rectal) and parenteral (intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intradermal) routes, as well as provide an overview of other important routes (transdermal, inhalational, topical, intranasal, ocular, otic, and vaginal) for completeness.

Introduction to Drug Administration Routes

Drug administration routes have evolved in tandem with advances in pharmacology, formulation science, and patient-centered care. The route chosen can determine the onset of action, the bioavailability of the drug, and the extent of any first-pass metabolism. For instance, drugs given orally must survive the acidic environment in the stomach as well as liver metabolism before entering systemic circulation, whereas those administered intravenously bypass these barriers.1 Additionally, patient convenience is a critical consideration, as routes such as oral, sublingual, or buccal can be more comfortable for prolonged therapy, while intramuscular or subcutaneous may be necessary for drugs that cannot be effectively absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Before delving deeply into the specifics of each route, it is valuable to recall some basic principles:• Bioavailability: The fraction of the administered dose that reaches the systemic circulation unchanged.

• Onset of action: The duration from drug administration to observable pharmacological effect.

• First-pass metabolism: The hepatic (liver) metabolism that a drug undergoes before reaching systemic circulation for the first time, which can significantly reduce its bioavailability when given orally.

• Patient compliance: The ease or difficulty with which a patient can adhere to the prescribed therapy, often influenced by the route of administration. with these foundational concepts, we move first to the enteral routes, which include oral, sublingual, buccal, and rectal drug delivery methods. Afterwards, we address the parenteral routes, which encompass intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intradermal injections.

Enteral Routes of Drug Administration

Enteral routes involve delivering medication through the gastrointestinal tract, typically starting with the mouth (oral) or mucous membranes (sublingual/buccal), or even through the rectum (rectal route). These methods generally rely on GI absorption to transport the medication into systemic circulation—except for sublingual and buccal, which can bypass first-pass metabolism to varying degrees. Below, we detail each enteral route and explore its key advantages and disadvantages.

Oral Route

The oral route is the most frequently used form of drug administration worldwide because of its simplicity, convenience, and cost-effectiveness. Patients generally find it straightforward to swallow tablets, capsules, or liquids, making oral therapy suitable for long-term treatment strategies such as managing hypertension or diabetes.

Common forms for oral administration include:

• Tablets (including extended-release variants)

• Capsules

• Solutions

• Suspensions

• Powders (sometimes dissolved in water)

Advantages of the Oral Route:

- High Patient Comfort and Compliance: Most patients accept this route without difficulty due to its non-invasive nature.

- Cost-Effective: Oral formulations are typically cheaper to manufacture and store compared to specialized parenteral formulations.

- Easy Self-Administration: Patients can take medications in outpatient settings without specialized training or equipment.

- Variability in Dosage Forms: Extended-release coatings and protective formulations can be used to modify drug release patterns or shield sensitive drugs from stomach acid.

Disadvantages of the Oral Route:

- First-Pass Metabolism: Some drugs are extensively metabolized in the liver before reaching systemic circulation, reducing bioavailability and necessitating larger doses.

- Variable Absorption: Food intake, GI pH, and motility can influence the degree and speed of absorption, leading to unpredictable plasma drug levels.

- Contraindications in Certain Conditions: Unconscious, vomiting, or dysphagic patients (those who have difficulty swallowing) may not be able to take oral medications.

- Irritation of the GI Tract: Some drugs can irritate the gastrointestinal lining, causing nausea, ulcers, or other adverse effects.

Sublingual Route

Sublingual drug administration involves placing a medication (often a tablet or strip) under the tongue for rapid dissolution and absorption through the highly vascularized mucosal lining. By bypassing the stomach and, to a large extent, the liver, sublingual administration avoids extensive first-pass metabolism, resulting in a faster onset of action and higher bioavailability relative to oral dosing of the same drug.

Advantages of the Sublingual Route:

- Rapid Absorption and Onset: The dense capillary network beneath the tongue allows for near-immediate entry of the drug into systemic circulation, which is especially beneficial in emergency situations such as angina.

- Bypasses First-Pass Metabolism: Higher and more consistent plasma levels can be achieved for certain drugs like nitroglycerin.

- Ease of Administration: Patients can place the medication under the tongue without specialized equipment or significant training.

Disadvantages of the Sublingual Route:

- Unpleasant Taste: Some drugs have a bitter or unpleasant flavor that may lead to poor adherence.

- Limited Drug Suitability: Only drugs that are potent in small doses and stable in salivary conditions are suitable for sublingual administration.

- Patient Cooperation Required: Patients must keep the drug under the tongue without swallowing until it dissolves fully, which may be challenging for some.

Buccal Route

The buccal route places medication against the cheek’s mucous membrane, allowing absorption directly into systemic circulation through the oral mucosa. Similar to sublingual administration, the buccal method bypasses the first-pass effect, although drug absorption can be slower than sublingual due to slightly less vascularization in the buccal region compared to the sublingual region.

Advantages of the Buccal Route:

- Avoids Liver Metabolism: Like the sublingual route, the buccal route can spare drugs from hepatic first-pass metabolism to a large extent.

- Sustained Release Potential: Buccal tablets or films can be formulated to release the drug more gradually, maintaining a relatively steady plasma concentration.

- Non-Invasive and Convenient: Simple to administer and does not require needles or advanced medical training.

Disadvantages of the Buccal Route:

- Possible Mucosal Irritation: Individuals with sensitive oral tissues may experience discomfort.

- Holding the Drug in Place: Patients may need to keep the dosage form between the cheek and gum for prolonged periods.

- Drug Suitability Limitations: Similar to sublingual administration, not all medications can be formulated for buccal administration.

Rectal Route

Rectal administration can be accomplished via solutions, suppositories, or enemas. In many cases, it is utilized for local effects (such as treating hemorrhoids or inflammatory bowel diseases), but it can also serve systemic purposes, particularly when an individual cannot take medications by mouth.

Advantages of the Rectal Route:

- Partial Avoidance of First-Pass Effect: Approximately 50% of the drug absorbed from the rectum bypasses hepatic metabolism, potentially improving bioavailability.

- Useful for Patients Unable to Take Oral Medications: It is often preferred when oral administration is not feasible—e.g., unconscious patients or those with severe nausea or vomiting.

- Local Effects: Rectal route can target certain conditions in the rectum or distal colon effectively, requiring smaller doses.

Disadvantages of the Rectal Route:

- Patient Discomfort or Embarrassment: Cultural and personal preferences often make rectal administration less acceptable.

- Variable Absorption: The presence of fecal matter and irregular blood flow can lead to erratic absorption.

- Limited Drug Forms: Fewer medications are available in rectal dosage forms compared to oral formulations.

Parenteral Routes of Drug Administration

The term “parenteral” refers to routes of drug administration that do not utilize the gastrointestinal tract. Instead, these methods involve injections or infusions, allowing medication to be delivered directly into or near systemic circulation. Parenteral routes are typically chosen when rapid onset of action is required, when a drug is poorly absorbed or inactivated by the GI tract, or when a patient cannot take drugs orally.

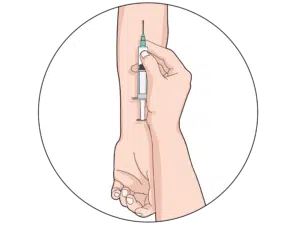

Intravenous Route (IV)

Intravenous administration is the direct infusion or injection of a drug into a vein, providing 100% bioavailability. IV delivery is often used in hospital settings for acute conditions, critical care, and for administering large volumes of fluid or irritating drugs that require precise control over plasma concentration.

Advantages of the IV Route:

- Immediate Onset: The drug enters systemic circulation almost instantly, which is crucial in emergencies (e.g., cardiac arrest, severe allergic reactions).

- Controlled Administration: Dosage, rate of infusion, and therapeutic level in the bloodstream can be tightly monitored and adjusted.

- Suitable for Irritating Drugs: Substances that might irritate other tissues can be well-tolerated intravenously with proper dilution.

- Complete Bioavailability: Because there is no absorption phase, the entire administered dose enters the bloodstream.

Disadvantages of the IV Route:

- Invasive Technique: Requires trained medical personnel and sterile equipment, increasing procedure costs and risk.

- Risk of Complications: Potential for phlebitis, infection at the injection site, and infiltration if the drug leaks into surrounding tissues.

- Less Reversibility: Once administered, it is difficult to reverse or retrieve the drug if adverse reactions occur.

- Patient Discomfort: Frequent IV insertions can cause pain and anxiety.

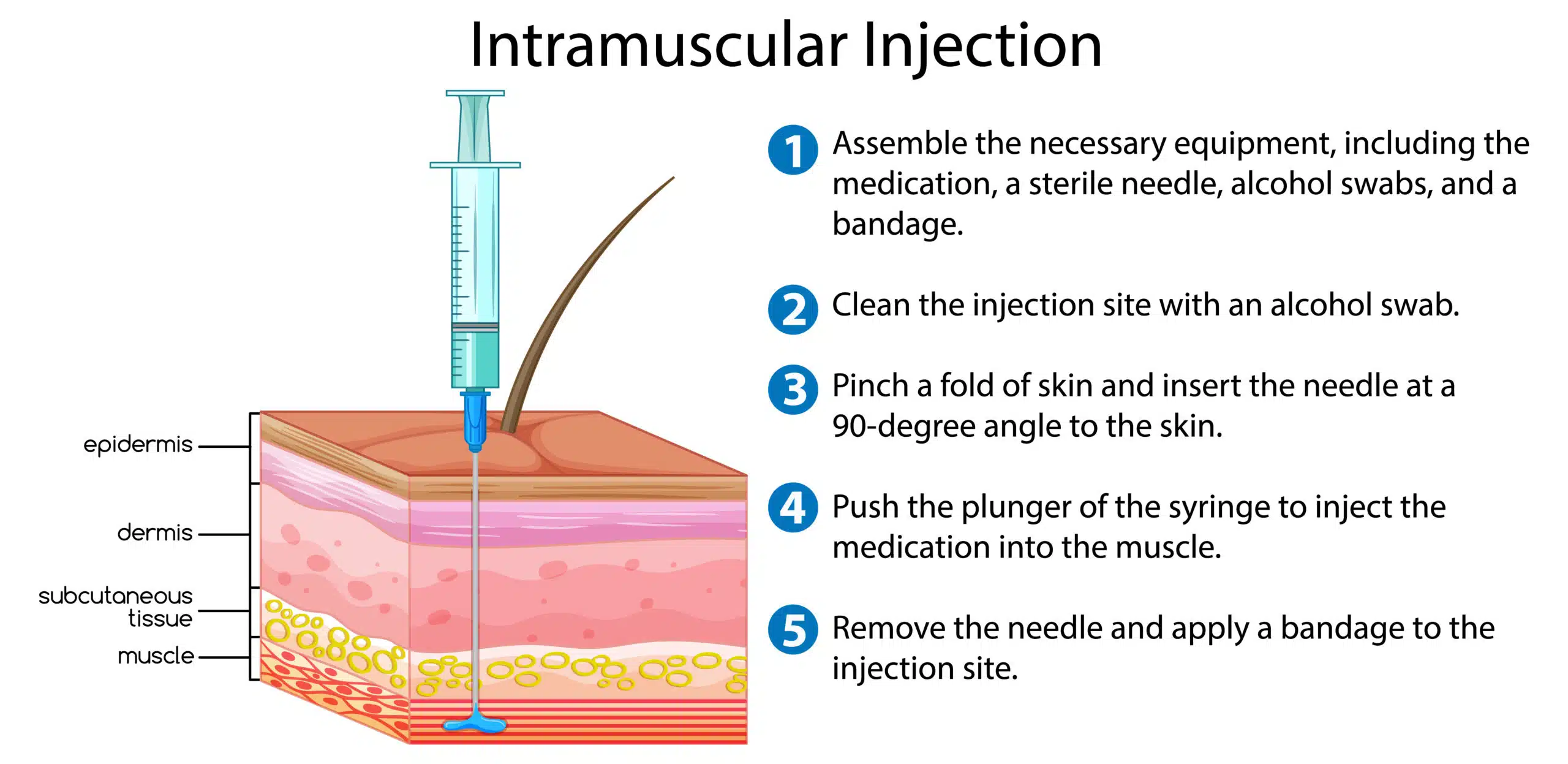

Intramuscular Route (IM)

In the intramuscular route, medications are injected into skeletal muscles such as the deltoid, vastus lateralis (thigh), or gluteal muscles. Muscle tissue is highly vascularized, enabling faster absorption compared to subcutaneous injections. IM injections are commonly used for vaccines, analgesics, and certain antibiotics.

Advantages of the IM Route:

- Relatively Quick Absorption: Faster than subcutaneous due to better blood supply, typically taking 10–30 minutes for onset.

- Depot Preparations: Oily or crystalline suspensions can offer sustained drug release over weeks or months (e.g., certain antipsychotics).

- Suitable for Moderate Volumes: Usually allows for 1–5 mL of fluid depending on the muscle group. of the IM Route:

- Invasive and Uncomfortable: Injections can be painful, may cause muscle soreness or hematoma.

- Risk of Nerve or Vascular Damage: Poor technique can injure nerves or blood vessels.

- Absorption Variability: Blood flow variations, exercise, and local temperature can influence absorption rates.

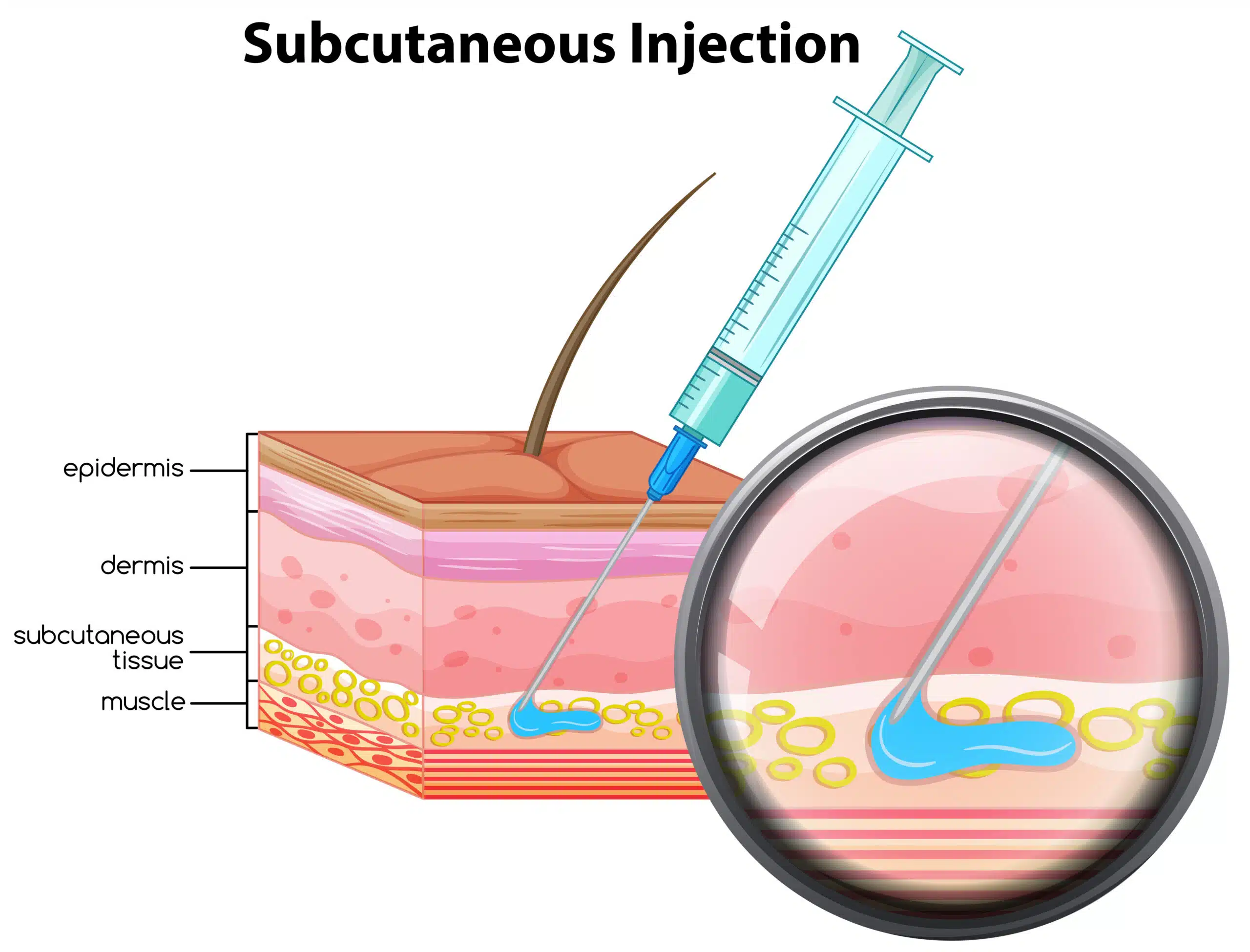

Subcutaneous Route (SC or Subcut)

Subcutaneous injections place drugs into the layer of fatty tissue beneath the skin but above the muscle layer. Common sites include the upper outer arm, the abdomen, and the anterior thigh. Insulin and certain anticoagulants (e.g., heparin) are frequently administered this way.

Advantages of the Subcutaneous Route:

- Easy Self-Administration: Many patients with chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes) learn to self-inject, boosting compliance.

- Sustained Absorption: The generally lower vascularity of subcutaneous tissue provides a slower, more prolonged release into systemic circulation.

- Less Painful than IM for Some Individuals: Thinner needles and shallower injection depth can be more tolerable for routine injections.

Disadvantages of the Subcutaneous Route:

- Limited Volume: Typically restricted to small volumes (1–2 mL), making it unsuitable for large-dose administration.

- Slower Onset: Although beneficial in cases needing slow release, it can be a disadvantage when rapid effect is required.

- Tissue Irritation: Certain formulations can cause local irritation, bruising, or necrosis if improperly injected.

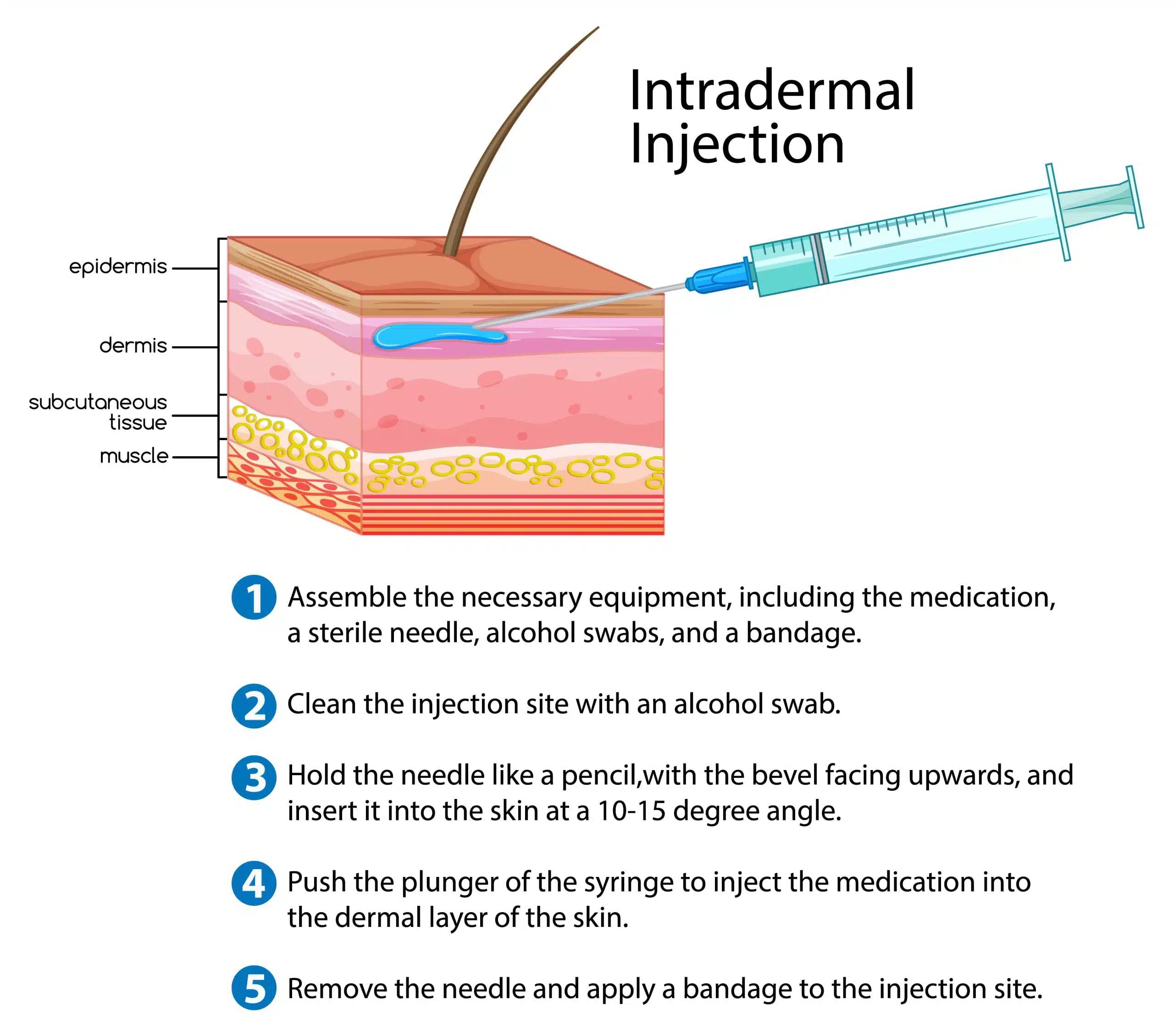

Intradermal Route (ID)

Intradermal injections are administered into the dermis layer of the skin, just below the epidermis. They are commonly used for diagnostic purposes (e.g., tuberculin skin testing) and for certain vaccines.

Advantages of the Intradermal Route:

- Diagnostic Utility: Allows for controlled evaluation of immune response, as with allergy tests and tuberculosis screening.

- Minimal Systemic Absorption: The medication remains localized, aiding in diagnostic observation.

- Reduced Risk of Systemic Side Effects: Because the dose is typically small, systemic adverse effects are minimal.

Disadvantages of the Intradermal Route:

- Limited Use Cases: Primarily diagnostic or immunologic testing; rarely used for standard drug therapy.

- Technical Challenge: Requires skill to ensure the injection is properly placed in the dermis.

- Small Volume Only: Minimal volumes (0.1–0.5 mL) can be injected, limiting the types of drugs that can be administered by this route.

Other Significant Routes of Drug Administration

In addition to the core enteral and parenteral routes described above, several other routes exist for specialized or alternative delivery of medications. While these may not always be the first choice, they are essential under specific clinical circumstances.

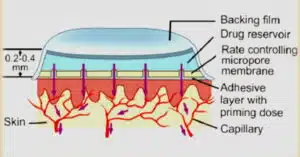

Transdermal Route

Transdermal administration delivers medication through the skin via patches or gels (e.g., nicotine patches for smoking cessation, fentanyl patches for pain control). The drug slowly migrates through the layers of the skin into systemic circulation.

Advantages:

• Steady, Prolonged Release: Can maintain consistent plasma concentrations over extended periods.

• Improved Compliance: Once a patch is applied, it can work for hours or days.

• Reduced GI and Hepatic Interference: Bypasses the digestive system and first-pass metabolism.

Disadvantages:

• Limited to Lipophilic Drugs: Only molecules able to penetrate the lipid-rich stratum corneum are appropriate for transdermal delivery.

• Skin Irritation: Prolonged contact with patches can lead to local irritation or allergic reactions.

• Slow Onset: It can take hours for sufficient drug to accumulate in systemic circulation.

Inhalation Route

The inhalation route targets the respiratory tract primarily, introducing drugs in the form of aerosols, gases, or fine powders through inhalers or nebulizers. This route is common for bronchodilators (e.g., albuterol) and anesthetic gases.

Advantages:

• Rapid Onset for Respiratory Conditions: Delivers the drug directly to the site of action in the lungs, reducing systemic side effects.

• High Local Concentrations: Ideal for asthma or COPD management, as it maximizes drug deposition in disease-affected tissues.

• Lower Systemic Exposure: Potentially fewer systemic hazards.

Disadvantages:

• Device Dependence: Correct technique with inhalers or nebulizers is crucial for efficacy.

• Irritation of Airways: Sensitive patients may experience coughing, bronchospasm, or discomfort.

• Variable Absorption: Factors such as breathing patterns and disease state can alter how much drug reaches the alveoli.

Topical Route

Topical applications involve placing drugs on the skin or mucous membranes for localized or, occasionally, systemic effects. Examples include creams, ointments, lotions, and gels.

Advantages:

• Localized Delivery: Ideal for dermatological conditions, offering high drug concentrations directly at the site of action.

• Minimizes Systemic Effects: Usually keeps the active ingredient confined to the site of application, reducing systemic toxicity.

• Ease of Use: Generally painless and straightforward.

Disadvantages:

• Unsuitable for Large Doses: Limited ability to deliver significant systemic levels (unless formulated specifically as a transdermal patch).

• Skin Barrier Function: The stratum corneum can impede drug penetration, requiring specific formulation strategies.

• Potential for Messiness: Ointments and creams may transfer onto clothing or surfaces.

Intranasal Route

Nasal administration can deliver both local treatments (e.g., decongestants) and systemic drugs (certain peptides or hormone therapies). The nasal mucosa is vascular and offers relatively fast absorption with partial bypass of first-pass metabolism.

Advantages:

• Rapid Absorption: Vascular nasal mucosa can facilitate fast drug uptake.

• Bypasses Hepatic Metabolism: Can lead to higher bioavailability for specific peptides or hormones (e.g., desmopressin).

• Easy Access: Self-administration of sprays or drops is simple.

Disadvantages:

• Nasal Irritation: Chronic use can damage nasal mucosa.

• Limited Formulations: Mildly lipophilic or specialized formulations are necessary.

• Short Residence Time: The nasal cavity’s clearance mechanisms quickly remove foreign substances.

Ocular (Eye) Route

Ophthalmic preparations (e.g., eye drops, ointments, gels) deliver drugs directly to the eye. They are primarily used to manage local conditions, such as glaucoma, infections, or inflammation.

Advantages:

• Targeted Therapy: High local concentration in ocular tissues.

• Minimizes Systemic Absorption: Less risk of systemic side effects if dose remains localized in the eye.

• Direct Access to the Affected Site: Avoids the complexities of systemic routes.

Disadvantages:

• Limited Penetration: The corneal barrier is restrictive, necessitating special formulations.

• Frequent Dosing: Tear drainage and blinking often remove eye medications rapidly, leading to short-lasting effects.

• Patient Technique: Incorrect instillation can reduce therapeutic benefits.

Otic (Ear) Route

Otic or auricular administration is specific to treating conditions of the ear canal, such as infections, inflammation, or cerumen (earwax) buildup. Preparations include antibiotic or antifungal ear drops.

Advantages:

• Direct Local Treatment: Targets the external and middle ear canal with minimal systemic exposure.

• Reduced Systemic Side Effects: Lower risk of adverse events.

Disadvantages:

• Limited Systemic Value: Otic route is generally unsuitable for systemic therapy.

• Possible Discomfort: Some solutions may cause temporary pain or irritation.

• Patient Positioning: Proper application can be cumbersome, especially for individuals with disabilities or children.

Vaginal Route

Vaginal administration is used for local treatments like antifungals, contraceptives, or hormone replacement therapy. Suppositories, creams, and rings can be placed in the vaginal canal.

Advantages:

• High Local Concentration: Beneficial for treating infections, dryness, or hormonal deficiencies in the vaginal area.

• Lower Systemic Absorption: Minimizes systemic exposure and side effects.

• Bypass of GI Tract: Avoids degradation by stomach acid or intestinal enzymes.

Disadvantages:

• Cultural Sensitivity: Some patients may be uncomfortable with this route.

• Variable Absorption: Vaginal secretions, pH changes, and cyclic variations can affect drug efficacy.

• Limited Systemic Use: Primarily for conditions involving the reproductive tract.

Intra-articular and intrathecal routes

Specialized methods of drug delivery are used to treat specific conditions.

Intra-articular

#Illustration of Intra-articular injection

Intra-articular drug delivery involves the injection of medication directly into the joint space. It is commonly used to treat inflammatory conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout.

Advantages:

- Provides targeted drug delivery to the affected joint.

- Rapid onset of action.

- High drug concentration is achieved in the joint fluid.

- Minimizes systemic side effects.

Disadvantages:

- Requires invasive procedures and specialized equipment.

- Risk of joint infection, bleeding, or damage.

- Limited duration of effect.

- May not be suitable for all patients.

Intrathecal

Intrathecal drug delivery involves the injection of medication directly into the spinal canal, which allows for drug delivery to the spinal cord and brain. It is commonly used to treat chronic pain, spasticity, and movement disorders.

Advantages:

- Provides targeted drug delivery to the central nervous system.

- Lower doses of medication are required compared to systemic administration.

- Can provide long-lasting pain relief or symptom control.

- Minimizes systemic side effects.

Disadvantages:

- Requires invasive procedures and specialized equipment.

- Risk of infection, bleeding, or damage to the spinal cord.

- Limited duration of effect.

- May not be suitable for all patients.

Intra-articular and intrathecal routes of drug administration are important methods of drug delivery used to treat specific conditions. While they provide targeted drug delivery with minimal systemic side effects, they also carry risks and require specialized equipment and expertise to ensure safe and effective treatment.

Factors Influencing the Choice of Administration Route

Selecting the optimal route of drug administration requires clinicians to weigh several intersecting factors:

• Drug Chemistry: The molecule’s stability, lipophilicity, solubility, and susceptibility to enzymatic degradation heavily guide whether the GI route is feasible or if parenteral administration is warranted.

• Onset and Duration Requirements: Acute pain relief or urgent conditions (e.g., cardiac arrest) often necessitate IV or sublingual routes. Longer-term therapy might favor oral or transdermal routes that offer sustained release.

• Patient-Specific Considerations: Age, cognitive ability, acceptance of certain routes, medical conditions complicating swallowing, and lifestyle factors all shape the appropriate choice.

• Safety Profile and Side Effects: Some highly potent or irritating compounds must be delivered intravenously with dilution. Others, like large peptide molecules (insulin), are destroyed in the GI tract, prompting subcutaneous administration.

• First-Pass Metabolism Implications: Oral drugs that have high hepatic extraction might be more effectively delivered sublingually, rectally, or parenterally to maximize bioavailability. Advantages and

Disadvantages Across Routes: A Summary

Every route presents a unique profile of benefits and drawbacks. To encapsulate:

Enteral Routes

• Oral: Comfortable, cost-effective, but subject to first-pass metabolism and GI unpredictability.

• Sublingual/Buccal: Rapid onset, bypasses extensive hepatic metabolism, but limited to small, highly potent molecules, and demands patient cooperation.

• Rectal: Suitable when oral administration is not possible; partially avoids first-pass metabolism, yet can be uncomfortable with variable absorption. Routes

• IV: Immediate effect, 100% bioavailability, but requires skill, equipment, and poses higher risks for complications.

• IM: Moderate onset, larger volumes possible, can use depot formulations, yet can be painful and has absorption variability.

• Subcutaneous: Easy to self-administer, slower more controlled absorption, but limited to small volumes and somewhat delayed onset.

• Intradermal: Useful for testing or very localized introduction, but largely restricted to small volumes under specialized circumstances.Other Routes

• Transdermal: Sustained release, convenient, but suitable for only specific drugs and potential for skin irritation.

• Inhalation: Rapid localized effect, minimal systemic side effects, reliant on proper technique, risk of airway irritation.

• Topical: Great for local conditions, limited systemic use, risk of local irritation.

• Intranasal: Fast absorption, partial bypass of first-pass, potential nasal irritation or limited formulations.

• Ocular/Otic: Useful for local problems, minimal systemic impact, technique-sensitive, shorter drug retention times.

• Vaginal: High local concentration for reproductive issues, but variable absorption and patient acceptability challenges.

Strategies to Optimize Therapy

To optimize therapy, clinicians often complement route selection with dosing schedules, formulation modifications (e.g., controlled-release capsules, multi-layer tablets, advanced transdermal patch technologies), and patient education:

• Selecting the Right Dosage Form: Some drugs benefit from microencapsulation or nanoparticle formulations to improve solubility, stability, or targeted release.

• Patient Training: Whether it is proper inhaler technique or subcutaneous injection instructions, education reduces errors and adverse effects.

• Monitoring and Follow-Up: Blood level checks or clinical endpoints guide dose adjustments, ensuring that the chosen administration route and dose remain effective and safe.

• Switching Routes if Needed: Patients may start on an IV infusion in a hospital setting and transition to oral medication once stabilized. This step often reduces cost and improves quality of life.

Clinical Scenarios Illustrating Route Selection

Below are several examples that illustrate why certain routes may be chosen based on patient-specific factors and urgency of delivery.

• Acute Myocardial Infarction: Rapid administration of nitroglycerin sublingually allows immediate vasodilation and symptom relief, bypassing the slow GI absorption and first-pass metabolism.

• Chronic Pain: Transdermal fentanyl patches provide steady plasma levels for extended pain relief, improving adherence and comfort compared to repeated oral doses.

• Diabetic Management: Insulin is administered subcutaneously due to its protein nature; oral intake would degrade it in the GI tract. Patient education on injection sites and rotation is critical.

• Seizure Control: Rectal diazepam can be lifesaving for acute seizure episodes in pediatric or cognitively impaired patients who cannot swallow oral medication.

• Severe Infection: IV antibiotics deliver high plasma levels quickly, crucial in septic patients where timing is critical. The route also bypasses potential GI irritation and absorption unpredictability.

Conclusion: Importance of Tailored Approach

The selection of a drug administration route is a nuanced process, hinging on molecular properties, clinical urgency, patient characteristics, and pharmaceutical formulations. Enteral routes—encompassing oral, sublingual, buccal, and rectal—are typically first-line in many non-emergency settings due to accessibility, cost benefits, and convenience. However, parenteral routes—intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intradermal—are essential in emergency settings, when the drug is not orally bioavailable, or to deliver precise dosages with immediate or sustained release as needed.

Every route has its own set of advantages and potential pitfalls that must be balanced against therapeutic goals, risk tolerance, and patient preferences. Oral administration may be favored for chronic conditions but is suboptimal for drugs with high first-pass metabolism. Sublingual and buccal provide rapid absorption but require specific drug properties and patient cooperation. Rectal administration can fill a niche role in patients unable to use the oral route, albeit with some discomfort and variability in absorption. Intravenous injections guarantee complete bioavailability and swift action but present invasiveness and require professional administration. Intramuscular and subcutaneous injections can solve absorption issues, though each introduces practical challenges like discomfort or volume limitations. Intradermal injection is specialized almost exclusively for diagnostic or immunologic evaluations. modalities, such as transdermal patches and inhalational, topical, intranasal, ocular, otic, and vaginal routes broaden the spectrum of options to suit specific clinical contexts. These routes can provide localized effects, steady-state drug levels, or bypass first-pass metabolism.

Ultimately, a successful therapeutic intervention often rests on selecting the most appropriate route and formulation for each patient’s distinct physiological needs and treatment demands. considering all factors—urgency, patient comfort, drug properties, cost, onset and duration needed, and risk of side effects—healthcare professionals must employ a comprehensive, individualized methodology in choosing a drug route. By doing so, medications are more likely to be delivered effectively, safely, and in a manner that promotes adherence, fulfilling the primary objective of maximizing therapeutic benefit while minimizing harm. sum, the escape from a one-size-fits-all perspective on drug administration is vital. Clinicians and pharmacists play a pivotal role in explaining to patients why certain routes are chosen, providing education on proper usage, and adjusting therapy as patient status evolves. Through these collaborative efforts, the intricacies of pharmacokinetics and route of administration become potent tools to enhance patient outcomes, paving the way for optimized medication therapy in today’s multifaceted healthcare landscape.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Always consult with a healthcare professional before making any decisions related to medication or treatment.

[…] Routes of Drug Administration […]