Methanol (methyl alcohol, wood alcohol) is a simple aliphatic alcohol with significant toxicological importance. It is colorless, volatile, and commonly used as a solvent, antifreeze, fuel, and in industrial chemical processes. Accidental or intentional ingestion of methanol, as well as inhalation or dermal exposure, can result in severe toxicity and death. The cardinal feature of methanol poisoning is the rapid development of profound metabolic acidosis and significant end-organ damage, especially to the central nervous system and optic nerves, which are frequently associated with visual disturbances, including irreversible blindness (Goodman & Gilman, 14th ed.; Katzung, 16th ed.; Rang & Dale, 9th ed.).

Chemistry and Sources of Exposure

Methanol is found in a wide array of household and industrial products: windshield washer fluids, solvents, paint removers, antifreeze, carburetor cleaners, dyes, and fuel for camping stoves. Illicitly distilled alcohol (“moonshine” or “hooch”) may be contaminated with methanol, often leading to outbreaks of poisoning, especially in regions where ethanol is banned or difficult to obtain. Exposure can occur via ingestion, inhalation of large quantities, or (rarely) absorption through the skin (Goodman & Gilman).

Toxicokinetics and Metabolism

After ingestion, methanol is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, with peak blood concentrations typically reached within 30–60 minutes. The primary metabolism occurs in the liver via a two-step process:

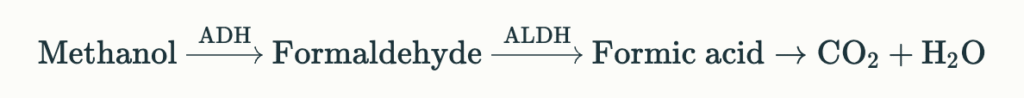

- Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) converts methanol to formaldehyde.

- Aldehyde dehydrogenase then oxidizes formaldehyde to formic acid (formate).

Formic acid is the major toxic metabolite responsible for metabolic acidosis and end-organ effects (Katzung, Table 58–4; Goodman & Gilman Ch. 49).

The sequential pathway can be summarized as:

The elimination half-life of methanol is increased in the presence of active metabolites and absent concurrent ethanol ingestion, as ethanol preferentially saturates ADH and is metabolized first, thereby delaying methanol toxicity (Rang & Dale).

Pathophysiology

Methanol itself is only weakly toxic; the primary mechanism of toxicity is the accumulation of formic acid, which induces:

- Profound, high anion gap metabolic acidosis

- Direct cytotoxicity to retinal, optic nerve, and basal ganglia cells

- Mitochondrial dysfunction due to inhibition of cytochrome oxidase, causing hypoxia at the cellular level

Optic toxicity is particularly notable, as the retina and optic nerve are highly susceptible to formic acid, leading to blurred vision, photophobia, and potentially permanent blindness (Katzung; Goodman & Gilman).

Clinical Features

Latent Period

Following exposure, there is usually a latent period (6–30 hours, longer if ethanol co-ingested) where symptoms are minimal or absent. This period reflects the time required for methanol conversion into toxic metabolites.

Early Symptoms

Symptoms after this latent interval are often nonspecific and may include:

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Mild central nervous system depression (unlike ethanol, methanol itself produces little inebriation)

Ocular Symptoms

Distinctive features are ocular toxicity, which may present as:

- Blurred vision (“looking through a snowstorm”)

- Photophobia

- Visual field defects

- Complete visual loss (central scotomata)

- Dilated, sluggish pupils with absent light reflex in severe cases

- Papilledema, as seen on fundoscopy

Severe and Late Manifestations

- Seizures

- Coma

- Respiratory depression or failure (secondary to profound acidosis)

- Renal failure

- Pancreatitis

- Death

Timeline

Symptoms can evolve rapidly, and untreated, methanol poisoning may cause death within 24–48 hours after ingestion. Even small amounts (~10 mL) may cause blindness, and 30 mL can be fatal (Rang & Dale; Goodman & Gilman).

Diagnosis

Laboratory Findings

The diagnosis of methanol poisoning is based on clinical presentation, a high index of suspicion (especially with possible access to methanol-containing products), and characteristic laboratory findings:

- Severe high anion gap metabolic acidosis

- Decreased serum bicarbonate

- Low pH (often <7.0)

- Large base deficit

- Elevated osmolal gap (early finding; may be normal late)

- Increased anion gap (from formic acid accumulation)

- Blood methanol level (if available; >20 mg/dL often treated)

- Visual abnormalities on examination

Differential diagnoses include poisoning by other toxic alcohols (ethylene glycol, isopropanol, diethylene glycol), salicylates, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, and renal failure (Goodman & Gilman).

Management

Principles

Management of methanol poisoning is based on:

- Inhibition of methanol metabolism to toxic metabolites

- Correction of metabolic acidosis

- Removal of methanol and its metabolites

- Supportive care and monitoring

Initial Stabilization

- ABCDE approach

- Airway protection, breathing, circulation support.

- Oxygen, IV fluids, correction of hypotension.

- Early recognition and triage to intensive care for patients with severe poisoning.

Antidotal Therapy

1. Fomepizole

- First-line antidote (unless unavailable).

- Competitively inhibits ADH, preventing methanol conversion to toxic metabolites.

- Acute dosing: 15 mg/kg IV loading, then 10 mg/kg IV every 12 hours. After 48 hours or 4th dose, increase to 15 mg/kg due to increased metabolism (Goodman & Gilman; StatPearls).

- Continue until methanol level is <20 mg/dL and acidosis is corrected.

2. Ethanol

- Alternative antidote, when fomepizole is not available.

- Ethanol is a competitive substrate for ADH, with a higher affinity than methanol.

- Requires careful dosing to maintain serum ethanol concentration ~100 mg/dL.

- Can induce inebriation and hypoglycemia, thus requiring close monitoring.

3. Folic (or folinic) acid

- 1–2 mg/kg IV every 4–6 hours.

- Enhances the conversion of formic acid to carbon dioxide and water. Evidence for clinical effectiveness is mainly theoretical, but recommended in most cases.

Correction of Acidosis

- Severe metabolic acidosis should be treated aggressively.

- Sodium bicarbonate is titrated to maintain pH >7.3; large quantities may be required.

- Correction of acidosis lessens tissue damage, especially to the eye and nervous system (Rang & Dale; Katzung).

Extracorporeal Removal: Hemodialysis

- Reserved for severe cases (coma, severe acidosis, high methanol/anion gap, visual disturbances).

- Both methanol and its toxic metabolites are dialyzable.

- Indications (any one may suffice):

- Severe acidosis (pH <7.25)

- Visual symptoms

- Renal failure

- Serum methanol level >50 mg/dL or rising levels despite therapy

- Hemodialysis should be continued until methanol and formate levels are nontoxic and acidosis is corrected.

Supportive Care

- Monitor vital signs, airway, fluid status, cardiac rhythm, glucose (especially if ethanol administered).

- Treat seizures with benzodiazepines.

- Prevent complications (aspiration, infections).

- Monitor for progression of visual symptoms; early treatment is associated with improved outcomes.

Monitoring and Prognosis

- Eye signs often improve with early and adequate treatment.

- Permanent visual loss and neurological damage may persist if therapy is delayed.

- Acidosis resolved with therapy confers better prognosis.

- Long-term sequelae may include optic atrophy, basal ganglia damage (especially putamen necrosis), parkinsonism, and neuropsychiatric impairment.

Prevention

Methanol poisoning is preventable. Preventative strategies include:

- Proper labeling and storage of methanol-containing products separately from beverages.

- Education regarding the hazards of methanol, particularly in regions with a history of outbreaks from adulterated alcohol.

- Strict regulation and enforcement against spurious liquor trade.

- Professional supervision in workplace settings involving methanol.

Summary Table: Methanol Poisoning at a Glance

| Aspect | Feature |

|---|---|

| Absorption | Rapid after ingestion; inhalation and dermal less common but possible |

| Metabolism | By alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to formaldehyde; then by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to formic acid |

| Toxic Mechanism | Formic acid—causes metabolic acidosis, optic nerve injury, CNS depression |

| Key Symptoms | Headache, nausea/vomiting, visual disturbance (“snowstorm”), abdominal pain, coma; late: blindness, seizures, death |

| Lab Findings | High anion gap metabolic acidosis, elevated osmolal gap (early), visual impairment, blood methanol >20 mg/dL |

| Antidote | Fomepizole (preferred); ethanol (alternative, if fomepizole unavailable); folic/folinic acid |

| Supportive Care | ABC stabilization, sodium bicarbonate for acidosis, correction of electrolyte imbalances, hemodialysis in severe cases |

| Prognosis | Good with prompt therapy; poor if therapy delayed, associated with severe acidosis or coma |

Key Points from Authoritative Pharmacology References

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (14th ed.)

- Comprehensive description of the metabolism, pathophysiology, and treatment of methanol poisoning.

- Emphasizes the competitive inhibition of ADH and clinical strategies for antidotal therapy.

- Katzung’s Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (16th ed.)

- Detailed clinical algorithms for acute poisoning, including supportive measures, hemodialysis, and visual sequelae.

- Supported role for folinic acid (leucovorin) in accelerating formic acid metabolism.

- Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology (9th ed.)

- Pathophysiological mechanism underlying visual toxicity and CNS damage.

- Emphasis on aggressive treatment of acidosis and early use of ADH inhibitors.

Guidelines from StatPearls (2025) and clinical protocols (MSF, Oslo) reinforce these principles and stress the critical importance of early diagnosis, rapid onset of therapy, and the use of hemodialysis in advanced poisoning.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is methanol poisoning?

Methanol poisoning refers to toxicity caused by ingestion (or less commonly, inhalation/dermal absorption) of methanol-containing products. The toxic effects stem from its hepatic metabolism to formaldehyde and formic acid, which can lead to severe metabolic acidosis and organ toxicity, especially to the eyes and CNS.

2. What amount is dangerous?

Ingestion of as little as 10 mL can cause permanent blindness; 30 mL may be fatal. However, any suspected exposure warrants medical evaluation.

3. What is the recommended antidote?

Fomepizole is the first-line antidote for methanol poisoning, with ethanol as an alternative if fomepizole is unavailable. Both inhibit methanol metabolism to toxic metabolites. Folate supplementation is also advised.

4. Is activated charcoal useful?

No. Methanol is rapidly absorbed and activated charcoal is not effective in preventing its absorption or toxicity.

5. Why does methanol cause blindness?

Formic acid accumulation specifically damages the optic nerve and retinal cells, leading to characteristic visual disturbances and, often, irreversible blindness if not promptly treated.

6. Should patients always get hemodialysis?

Hemodialysis is indicated for severe poisoning (especially with visual abnormalities, severe acidosis, elevated methanol levels, or end-organ damage) as it effectively clears both methanol and formic acid.

7. Can outcomes be improved?

Yes—early recognition, administration of antidote, correction of acidosis, and, if needed, hemodialysis greatly improve prognosis.

References

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 14th Edition

- Katzung BG, Trevor AJ. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 16th Edition

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G. Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology, 9th Edition

- StatPearls – Methanol Toxicity (2025)

- MSF/Oslo University Hospital: Methanol Poisoning Guidelines (2023)

Quiz on Methonol Poisoning

Quiz on Methonol Poisoning

Medical Disclaimer

The medical information on this post is for general educational purposes only and is provided by Pharmacology Mentor. While we strive to keep content current and accurate, Pharmacology Mentor makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the post, the website, or any information, products, services, or related graphics for any purpose. This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment; always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition and never disregard or delay seeking professional advice because of something you have read here. Reliance on any information provided is solely at your own risk.