I. Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic disorder characterized by the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, which leads to troublesome symptoms, mucosal injury, and, in some cases, serious complications such as strictures or Barrett’s esophagus. GERD is one of the most prevalent GI disorders globally, affecting up to 20% of adults in Western populations, with substantial impact on quality of life and healthcare systems.

Core principles in GERD management include accurate diagnosis, identification of risk factors and phenotypes, and highly individualized therapy—including both lifestyle and pharmacological interventions, the latter forming the foundation for moderate-to-severe or complicated disease.

II. Pathophysiology

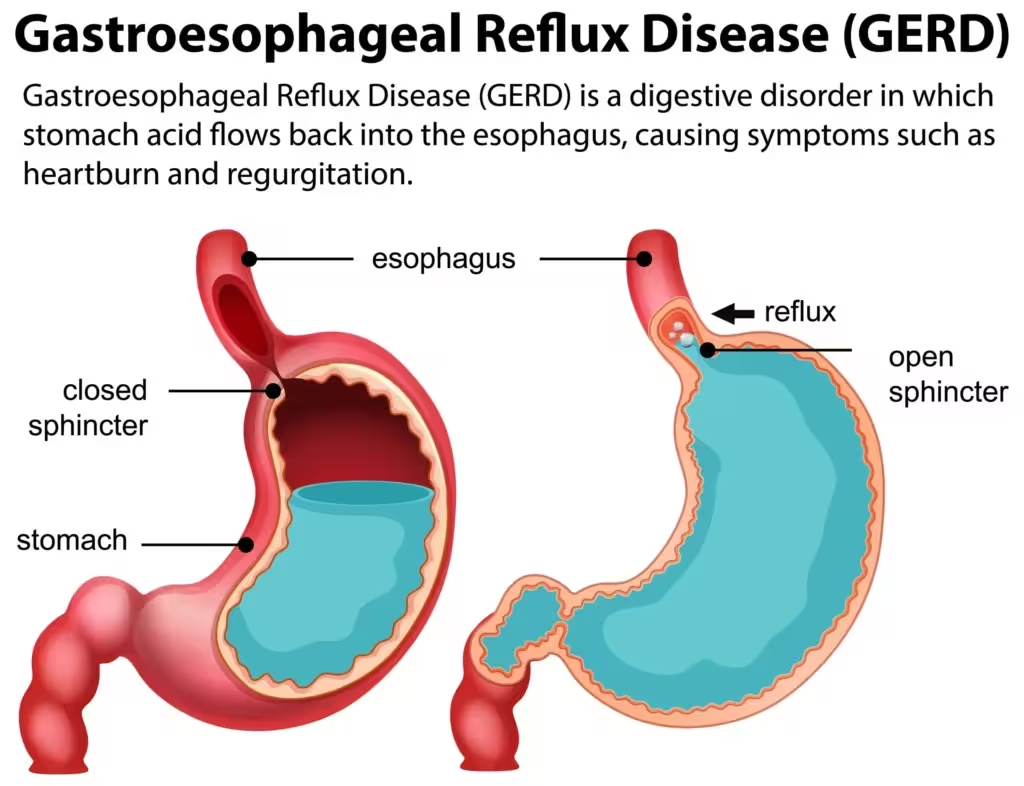

LES Dysfunction: The fundamental defect in GERD is failure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to prevent reflux. This can result from:

- Primary weakness of the LES muscle

- Transient LES relaxations (TLESRs)—often triggered by meals, certain foods, and supine posture

- Anatomical disruption (e.g., hiatal hernia)

- Factors increasing intra-abdominal pressure (obesity, pregnancy, chronic cough)

- Delayed gastric emptying and impaired esophageal clearance further potentiate symptoms and mucosal damage.

Gastric acidity: Even brief exposures of the esophageal mucosa to gastric acid (>pH 4) can trigger symptoms and, with chronicity, lead to inflammation (esophagitis), ulceration, strictures, or metaplastic changes (Barrett’s).

Symptoms:

- Typical: Heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain

- Atypical/Extra-esophageal: Chronic cough, laryngitis, asthma-like symptoms, dental erosion

- Alarm features: Dysphagia, odynophagia, significant weight loss, GI bleeding—necessitating early endoscopic evaluation

III. Therapeutic Goals

- Rapid symptom control (heartburn, regurgitation)

- Mucosal healing (particularly in erosive or complicated esophagitis)

- Prevention of recurrence, complications, and malignant transformation

- Patient education and long-term safety

IV. Pharmacologic Therapies for GERD

1. Antacids

Description: Antacids are over-the-counter agents containing aluminum, magnesium, calcium, or sodium bicarbonate salts. They offer rapid, short-lived relief via neutralization of gastric acid.

- Mechanism: Base + HCl → salt + H₂O (raising gastric pH)

- Clinical use: On-demand relief for mild, intermittent GERD or breakthrough symptoms while on maintenance drugs.

- Key agents: Calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide, aluminum hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate

- Adverse effects: Magnesium—diarrhea; Aluminum/calcium—constipation; risk of acid rebound, metabolic alkalosis (sodium bicarbonate)

- Limitation: Do not heal esophagitis; need frequent dosing.

2. H2 Receptor Antagonists (H2RAs)

Agents: Ranitidine (withdrawn in many countries), famotidine, cimetidine, nizatidine

- Mechanism: Competitively inhibit H₂ receptors on parietal cells → reduced histamine-stimulated and basal acid secretion

- Onset/duration: Slower onset than antacids; effect lasts 6–12 hours

- Dosing: Often once/twice daily; evening dosing key for nocturnal symptoms

- Clinical role:

- Mild-to-moderate, non-erosive GERD

- Step-down from PPIs for maintenance

- Adjunct for breakthrough symptoms

- Adverse effects: Headache, diarrhea, rare CNS effects (elderly), cimetidine—gynecomastia, drug interactions (CYP inhibition)

- Limitations: Tolerance (tachyphylaxis) with continuous use; less effective in severe GERD/erosive esophagitis

3. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

Cornerstone of therapy, especially for moderate/severe GERD or erosive disease.

- Agents: Omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, rabeprazole, dexlansoprazole

- Mechanism: Irreversibly block H⁺/K⁺-ATPase (the final pathway of gastric acid secretion) in parietal cells → potent, long-acting acid suppression

- Pharmacokinetics:

- Pro-drugs, best absorbed on empty stomach

- Peak effect: 1–4 days for maximal inhibition

- Once daily dosing suffices for most, but severe or nocturnal GERD may need BID dosing

- Clinical indications:

- Erosive esophagitis

- Symptomatic GERD not controlled on H₂RAs/antacids

- Barrett’s esophagus

- Maintenance after healing severe disease

- Adverse effects:

- Short-term: Headache, GI upset

- Long-term: Possible increased risk of fractures (osteoporosis), hypomagnesemia, C. difficile infection, renal dysfunction, vitamin B12 deficiency (prolonged use), possible drug interactions (clopidogrel, warfarin)

- Pearls:

- Take 30–60 min before meal, preferably breakfast

- Nearly all PPIs are interchangeable at equivalent doses

4. Prokinetic Agents

Role: Reserved for patients with motility disorders (impaired LES tone, gastroparesis) or when acid suppression alone is insufficient

- Agents: Metoclopramide (CNS-permeant D2 antagonist), domperidone (less CNS effect), rarely erythromycin

- Mechanisms:

- Enhance LES pressure

- Accelerate gastric emptying

- Improve esophageal peristalsis

- Indications: Adjunct in refractory GERD with documented motility disorder

- Limitations: Risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (metoclopramide: dystonia, tardive dyskinesia), especially in elderly; domperidone—arrhythmia risk (QT prolongation); rarely first-line

5. Mucosal Protective Agents

- Sucralfate: Forms a protective barrier over erosions/ulcers, adsorbing acid and pepsin; limited efficacy as monotherapy in GERD but may be adjunctive in esophagitis

- Alginic acid/Alginates: Form a viscous “raft” to prevent acid contact with the esophageal lining; symptomatic relief for mild/postprandial GERD

- Role: Adjunct for select patients (e.g., pregnancy, mild disease) or those intolerant of acid suppression

V. Individualizing Therapy

Patient & Disease-tailored Approaches

- Mild/intermittent GERD: Begin with lifestyle modifications + antacids or on-demand H2RAs.

- Persistent or severe symptoms, erosive esophagitis, or “alarm” features: Initiate PPI; assess after 4–8 weeks for healing or symptom improvement; titrate dose or switch if suboptimal response.

- Long-term maintenance: Taper to lowest effective regimen; intermittent (“on-demand”) or step-down to H2RA if possible.

- Special populations:

- Pregnancy: Antacids (calcium-containing), sucralfate generally safe; H2RAs or PPIs for severe/refractory cases

- Children: Weight-based dosing; careful use of prokinetics

- Elderly: Monitor for drug interactions, side effects (especially CNS)

VI. Non-Pharmacologic (Lifestyle) Measures

Essential for all patients:

- Elevate head of bed for nocturnal symptoms (6–8 inches)

- Avoid lying down after meals (wait ≥2 hours)

- Diet: Minimize trigger foods (fatty/spicy foods, caffeine, chocolate, alcohol, peppermint, citrus)

- Weight loss for overweight/obese patients (often dramatically reduces symptoms)

- Smoking cessation (impairs LES)

- Smaller meal volumes, avoid late-night eating, wear loose clothing

VII. Monitoring, Complications, and Follow-up

- Assess response after 2–8 weeks of therapy

- Endoscopy: Indicated for alarm symptoms, therapy failure, or surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus/complications

- Monitor for adverse effects of long-term therapy, especially with PPIs

- Barrett’s esophagus/strictures: May require indefinite PPI, consideration for endoscopic or surgical intervention

VIII. Future Directions in GERD Pharmacotherapy

- Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers (P-CABs): e.g., vonoprazan—faster, more potent acid suppression

- Improved prokinetic agents (selective serotonin, motilin agonists) with fewer adverse effects

- Endoscopic interventions: Stretta, transoral fundoplication for refractory GERD

- Microbiome modulation and biologics (experimental)

IX. Case Studies and Clinical Pearls

| Scenario | Recommended Approach | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Occasional heartburn | Antacids/H2RAs as needed | Lifestyle counseling crucial |

| Persistent, erosive esophagitis | Daily PPI for 8 weeks, then re-evaluate | Consider step-down after healing |

| Elderly with confusion on H2RAs | Switch to PPI, consider drug interactions | Monitor for B12, Mg, renal function |

| Nighttime symptoms | H2RA bedtime, PPI in AM, elevate bed | Split dosing may help |

| PPI failure | Confirm adherence/timing, add prokinetic (if gastroparesis), consider EGD | Rule out other conditions |

X. References

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13th Edition

- Katzung BG, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 15th Edition

- Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21st Edition

- American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Guideline: Management of GERD (2022)

- NICE Clinical Guideline: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults (2023)

This chapter delivers a comprehensive, evidence-based, and practical roadmap to GERD pharmacotherapy, suitable for high-level education, exam preparation, and clinical reference.

📚 AI Pharma Quiz Generator

🎉 Quiz Results

Medical Disclaimer

The medical information on this post is for general educational purposes only and is provided by Pharmacology Mentor. While we strive to keep content current and accurate, Pharmacology Mentor makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the post, the website, or any information, products, services, or related graphics for any purpose. This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment; always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition and never disregard or delay seeking professional advice because of something you have read here. Reliance on any information provided is solely at your own risk.