Introduction

Migraine is a debilitating primary headache disorder characterized by episodic attacks of throbbing or pulsating head pain, often accompanied by photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and in some cases, aura phenomena. Although once perceived purely as a vascular headache, recent advances in neuroscience underscore the neurovascular and inflammatory underpinnings of migraine. The complexity of its pathogenesis, which involves cortical spreading depression, trigeminal nerve activation, and the release of vasoactive neuropeptides, accounts for the multifaceted symptomatic profile.

The pharmacotherapy of migraine can be divided into two broad categories: acute (abortive) therapy aimed at terminating or reducing the severity of an ongoing attack, and prophylactic (preventive) therapy employed to reduce the frequency and intensity of recurrent episodes. Selecting the right medication, dose adjustment, and patient education constitute an essential, individualized strategy. This article provides a comprehensive overview of migraine pharmacotherapy, drawing upon the principles from Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (13th Edition), Katzung’s Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (15th Edition), and Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology (8th Edition).

Pathophysiology of Migraine

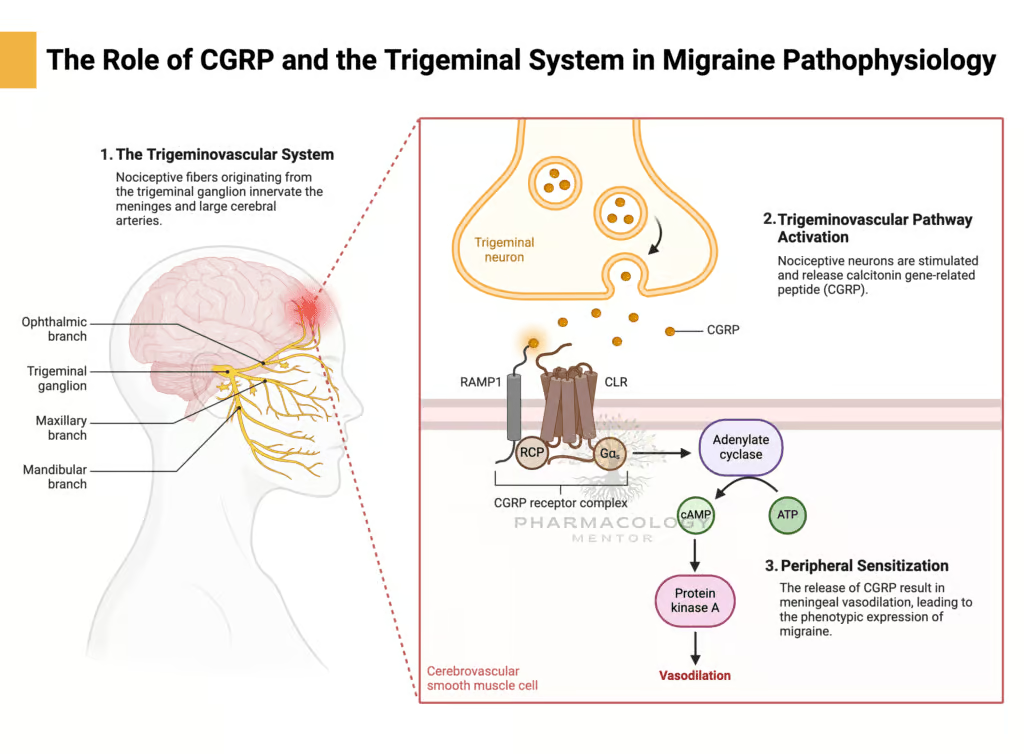

Trigeminovascular System

Central to migraine pathology is the activation of the trigeminovascular system, where trigeminal sensory fibers project to the meningeal blood vessels and the perivascular space. Pain arises when these fibers release pro-inflammatory neuropeptides—such as Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP), substance P, and neurokinin A—leading to vasodilation and neurogenic inflammation in meningeal arteries.

Cortical Spreading Depression

An additional mechanism, cortical spreading depression, refers to a wave of depolarization moving across the cortex, associated with aura and subsequent activation of meningeal nociceptors. This event can upregulate trigeminal responses, reinforcing inflammatory processes within the cranial vasculature.

Role of Serotonin (5-HT)

Migraine pathogenesis also highlights dysfunction in serotonergic pathways. Fluctuations in serotonin (5-HT) levels, particularly within the brainstem raphe nuclei, can facilitate or inhibit trigeminal activation. Medications targeting 5-HT₁B/₁D receptors (e.g., Triptans) underscore the critical inhibitory role of 5-HT on trigeminal nerve excitability and cranial vasculature vasodilation.

Importance of Genetics and Hormones

Migraines display a genetic predisposition, frequently running in families. Additionally, hormonal fluctuations, such as estrogen withdrawal during menses, can trigger migraine episodes. Recognizing and managing triggers (stress, certain foods, sleep disturbances) remain important non-pharmacological elements in overall migraine management.

Classification of Migraine and Treatment Goals

Migraine Types

- Migraine without aura: The most common form, characterized by unilateral, pulsatile pain progressing over 4–72 hours, accompanied by nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia.

- Migraine with aura: Includes transient visual, sensory, or language symptoms preceding or accompanying the headache.

- Chronic migraine: Headache (often migraine-like) on at least 15 days per month for more than three months, with a migrainous pattern on at least 8 days per month.

Treatment Objectives

- Acute (Abortive) Therapy: Rapidly relieve or moderate the pain and associated symptoms, restoring functional capacity.

- Prophylactic (Preventive) Therapy: Reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks, improving quality of life and minimizing medication overuse headaches.

Selecting a route of administration (oral, subcutaneous, nasal spray) can be influenced by the patient’s symptom pattern (e.g., severe nausea/vomiting may limit oral intake).

Acute (Abortive) Pharmacotherapy of Migraine

Simple Analgesics and NSAIDs

First-line for mild to moderate migraine attacks often involves NSAIDs or combination analgesics. Examples include:

- Ibuprofen (200–400 mg)

- Naproxen (500–750 mg)

- Diclofenac (50–100 mg)

- Aspirin (650–1000 mg)

- Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) in combination (e.g., with aspirin and caffeine)

These agents act by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, reducing meningeal inflammation. However, overuse (>15 days/month) may precipitate medication overuse headaches.

Combination Analgesics with Caffeine

Caffeine can enhance the absorption and analgesic efficacy of NSAIDs and acetaminophen by promoting mild vasoconstriction and augmenting central pain-relief pathways. Commercial analgesics often incorporate Caffeine at moderate doses with Aspirin or Acetaminophen.

Triptans (5-HT₁B/₁D Receptor Agonists)

A cornerstone in moderate-to-severe acute migraine management is the Triptan class. By selectively agonizing 5-HT₁B and 5-HT₁D receptors on intracranial blood vessels and trigeminal nerve endings, Triptans induce cranial vasoconstriction and inhibit neuropeptide release, curtailing inflammatory mediator release in the meninges.Common Triptans:

- Sumatriptan: The prototypical agent, available orally, subcutaneously, and intranasally. Dose ranges from 25–100 mg orally.

- Rizatriptan: Quick onset, orally disintegrating tablet form is convenient. Usual dose is 5–10 mg.

- Zolmitriptan: Oral, nasal spray forms. Typical dose of 2.5–5 mg.

- Almotriptan, Eletriptan, Frovatriptan, Naratriptan: Differ in half-lives/onset, but share a similar mechanism.

Clinical Pearls:

- Contraindications: Uncontrolled hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke/TIA, peripheral vascular disease.

- Adverse Reactions: Chest pressure, flushing, paresthesias. Rare but serious complications include coronary vasospasm.

- Drug Interactions: Avoid combining with Ergot derivatives or other vasoconstrictors within 24 hours. Serotonin Syndrome risk with SSRIs or MAO inhibitors.

Ergot Alkaloids

Historically central in migraine management, Ergot derivatives (e.g., Ergotamine, Dihydroergotamine) act non-selectively on 5-HT₁ receptors, alpha-adrenergic receptors, and dopamine receptors, causing prolonged vasoconstriction. Despite efficacy, their side effect profile and potential for ergotism (vasospastic complications, numbness, gangrene) have caused them to be largely supplanted by Triptans.

- Ergotamine: Oral, sublingual, rectal forms, often combined with caffeine.

- Dihydroergotamine (DHE): Nasal or parenteral routes. Less vasoconstrictive than ergotamine and better tolerated.

Clinical Pearls:

- Black Box Warning: Risk of severe peripheral ischemia when combined with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors.

- Co-administration with Triptans is discouraged (24-hour gap recommended).

- Contraindicated in significant cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, pregnancy.

Antiemetics/Dopamine Antagonists

Many migraine attacks involve prominent nausea and vomiting. Metoclopramide, Prochlorperazine, or Chlorpromazine can alleviate GI distress and enhance gastric emptying, improving absorption of oral medications. Intravenous or intramuscular formulations can be used in severe attacks or emergency department settings for rescue.

- Metoclopramide (10 mg IV/PO): Also has prokinetic properties.

- Prochlorperazine (5–10 mg IV/IM): Can reduce headache intensity.

- Potential side effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms, sedation.

CGRP Antagonists (Gepants) for Acute Migraine

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) plays a key role in migraine pathophysiology by promoting trigeminal vasodilation and nociceptive transmission. Gepants (small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists) constitute a new class of acute migraine therapy, offering an alternative to Triptans:

- Ubrogepant: Approved for acute migraine with or without aura.

- Rimegepant: Used both in the acute and prophylactic setting (low-dose version for prophylaxis).

- Benefit: No vasoconstrictive potential, suitable for those with cardiovascular risks.

- Drawback: Potential cost and relatively new market presence, so long-term data are limited.

Lasmiditan (5-HT₁F Agonist)

Another novel option is Lasmiditan, a 5-HT₁F receptor agonist that blocks trigeminal nociceptive signaling without causing vasoconstriction. This “neurally acting” anti-migraine agent is beneficial for individuals contraindicated to receive triptans. Commonly reported side effects include sedation and dizziness, requiring caution in activities requiring alertness.

Preventive (Prophylactic) Pharmacotherapy of Migraine

Indications for Preventive Therapy

Patients may benefit if they experience:

- Frequent (≥4 monthly) or severe migraine attacks.

- Significant functional impairment despite acute treatment.

- Contraindications or inadequate response to acute medications.

- Risk of medication overuse headache (excess analgesic/triptan consumption).

Prophylaxis aims to reduce the incidence and severity of attacks by stabilizing neuronal hyperexcitability, modulating inflammatory pathways, and minimizing triggers.

Non-Pharmacological Approaches

Lifestyle interventions (sleep hygiene, regular exercise, stress management), avoiding triggers (certain foods, odors, bright lights), and psychological therapies (biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy) complement prophylactic drugs.

Beta-Adrenergic Blockers

Beta-blockers are among the most commonly prescribed first-line prophylactic agents. The exact antimigraine mechanism remains unclear but may involve modulation of central catecholaminergic activity and reduced vasomotor reactivity.

- Propranolol: A non-selective agent, typically 80–240 mg/day.

- Metoprolol: A β₁-selective antagonist, 50–200 mg/day.

- Timolol: Another option.

Side effects: Fatigue, exercise intolerance, depression, sexual dysfunction. Contraindicated in asthma, certain conduction blocks.

Anticonvulsants

Valproic Acid (Valproate)

Valproic Acid (and its derivative Divalproex Sodium) effectively reduce neuronal excitability in migraine. Typical doses range from 500–1500 mg/day. Adverse effects include GI distress, tremor, weight gain, alopecia, and teratogenic risks (contraindicated in pregnancy). Regular monitoring of liver function and ammonia levels is advisable.

Topiramate

Topiramate modulates glutamate/GABA neurotransmission and stabilizes neuronal membranes. Common prophylactic dose: 50–100 mg/day. Potential side effects: cognitive slowing (“brain fog”), paresthesias, weight loss, and risk of nephrolithiasis. Women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception (associated with risk of fetal malformations).

Antidepressants

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) such as Amitriptyline are widely used off-label for migraine prophylaxis. They increase the synaptic levels of norepinephrine and serotonin, potentially downregulating pain pathways in the trigeminal system. A typical dose is 10–75 mg at bedtime. Side effects: sedation, weight gain, anticholinergic effects.

Other antidepressants (e.g., Venlafaxine) may offer prophylactic benefits, though data is not as robust as with TCAs.

Calcium Channel Blockers

Verapamil, a non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, can be used in migraine and cluster headache prophylaxis, though evidence is moderate. Doses (240–480 mg/day) can help stabilize vascular reactivity. Watch for bradycardia, constipation, and hypotension.

CGRP Pathway-Targeted Therapies for Prophylaxis

Monoclonal Antibodies

In recent years, monoclonal antibodies directed against CGRP or its receptor have transformed the prophylactic landscape. By binding either CGRP (ligand) or its receptor, these agents diminish migraine frequency.

- Erenumab (targets CGRP receptor)

- Fremanezumab, Galcanezumab, Eptinezumab (target CGRP ligand)

Typically administered subcutaneously (monthly or quarterly), they demonstrate a favorable safety profile and no vasoconstrictive properties. However, potential limitations include high cost and long-term data that remain under ongoing investigation.

Rimegepant (Oral CGRP Antagonist) for Prophylaxis

In addition to acute usage, a low-dose regimen of Rimegepant 75 mg every other day has been approved in some regions for migraine prophylaxis, offering an oral CGRP blockade approach for both acute and preventive management.

Botulinum Toxin Type A

Botulinum Toxin A (onabotulinumtoxinA) received approval for chronic migraine prophylaxis (≥15 headache days/month, with at least 8 being migrainous). Repeated injections in specific head/neck muscle sites every 12 weeks can reduce headache days. Mechanistically, it may inhibit the release of pain mediators from trigeminal nerve fibers. Treatment is relatively well tolerated, though potential side effects include neck pain, muscle weakness, and injection-site discomfort.

Other Agents and Emerging Strategies

ACE Inhibitors / ARBs

Small studies suggest that Lisinopril or Candesartan might offer prophylactic benefit, potentially via vascular or neurohumoral modulation. They remain off-label but can be considered when standard therapies are not tolerated.

Nutraceuticals and Supplements

Although data remains less robust than for prescription medications, certain supplements—like Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) (400 mg/day), Magnesium, and Coenzyme Q10—have some evidence for migraine prophylaxis. These are generally safe options for mild migraines or as adjunct therapy.

Non-Invasive Neuromodulation

Devices delivering transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcutaneous supraorbital neurostimulation, or non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation have garnered interest as prophylactic or acute interventions. While not strictly pharmacological, they represent an expanding portion of migraine management, especially for patients with medication contraindications.

Management of Special Populations

Pediatric Migraine

Pediatric migraine often responds to conservative measures and cautious analgesic use. Topiramate or Propranolol can be considered prophylactically. Triptans are approved in older children/adolescents for acute attacks, although dosing and formulations may vary.

Pregnancy and Lactation

Migraine can improve during pregnancy due to stable estrogen levels or worsen postpartum. Triptans (especially sumatriptan) are generally avoided unless benefits greatly outweigh risks, given the limited data. Propranolol or limited use of Amitriptyline can be prophylactic options if necessary. Non-pharmacological measures remain primary.

Geriatric Considerations

Comorbid conditions require caution (e.g., beta-blockers in COPD or peripheral arterial disease). Polypharmacy raises the risk of interactions. Triptans demand thorough cardiovascular evaluation in elderly patients.

Patients with Comorbidities

Selecting prophylactic medication based on comorbid diseases can be advantageous: for instance, Propranolol in patients with hypertension or anxiety, Topiramate in obese patients needing weight management, Amitriptyline in depressed or insomnia-prone individuals, etc.

Medication Overuse Headache (MOH)

Definition and Triggers

Excessive use of acute headache medications—like NSAIDs, opioids, or triptans (>10–15 days/month)—can lead to exacerbation of headache frequency, called medication overuse headache. Identifying and reversing overuse patterns are crucial to restoring the effectiveness of prophylactic therapy.

Management Approach

- Gradual or abrupt withdrawal of overused agents in a controlled manner.

- Initiate prophylaxis to reduce the need for rescue medication.

- Patient education on risk of daily analgesic use.

Practical Clinical Approaches

Stepwise Management

- Assess Attack Severity: Evaluate whether mild analgesics, NSAIDs, or combination therapy might suffice for mild-attacks.

- Moderate to Severe Attacks: Triptans are typically first-line unless contraindicated.

- Settings of Refractory Pain: Consider rescue with IV antiemetics, Dihydroergotamine, or short-term Steroids (e.g., dexamethasone) in an emergency department context.

- Prophylactic Selection: Match patient profiles (cardiac status, comorbidities, frequency of attacks) to the best agent (e.g., Beta-blocker, Anticonvulsant, or CGRP-targeted therapy).

Monitoring and Dose Titration

- Prophylactic agents often require 4–8 weeks to demonstrate full effect.

- Start with low doses, increment gradually to minimize side effects.

- Encourage headache diaries to track frequency, severity, and medication consumption.

Patient Education and Shared Decision-Making

Open discussion of side effects, realistic expectations (e.g., prophylaxis aiming for at least 50% reduction in attack frequency), and the need for consistent follow-up fosters adherence and better outcomes. Lifestyle modifications, routine sleep schedules, and stress management complement pharmacotherapy.

Current Trends and Future Developments

Pharmacogenetics

Exploration into pharmacogenomic signatures that predict an individual’s response to specific prophylactic agents (like certain gene variants impacting beta-blocker or topiramate effectiveness) holds promise for personalized migraine care.

Novel CGRP Agents and Beyond

The recent success of monoclonal antibodies and small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists suggests further expansions of targeted biological therapies. Agents acting on PACAP (pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide) pathways also generate significant interest.

Neuromodulation Synergies

Combining mild prophylactic pharmacotherapy with advanced neuromodulation devices—like single-pulse TMS or transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation—may reduce the overall drug burden and side effects for certain patients.

Safety, Adherence, and Cost Issues

Balancing Efficacy with Tolerability

A recognized challenge in migraine treatment is finding a regimen that effectively prevents or aborts attacks without intolerable adverse effects. For instance, Topiramate is effective but can cause cognitive slowing, while Beta-blockers might worsen fatigue or depression.

Adherence Barriers

- Side effects (weight gain with valproate, sedation with TCAs) often cause early discontinuation.

- Cost and insurance coverage restrictions hamper the accessibility of newer agents such as CGRP monoclonal antibodies.

- Reassurance and robust follow-up can ameliorate adherence issues.

Long-Term Monitoring

Periodic reassessment of prophylactic therapy is vital. Some individuals may be able to taper off prophylaxis if migraine frequency decreases significantly over time. Alternatively, prophylaxis might require escalation or switching if efficacy proves suboptimal or if side effects accumulate.

Summary of Major Agent Classes

- Abortive

- NSAIDs/Analgesics: Mild to moderate attacks.

- Triptans: Moderate to severe attacks, first-line for many patients.

- Ergot Alkaloids: Reserved for refractory or specific cases.

- CGRP Antagonists (Gepants): Alternative to triptans, used in acute rescue.

- 5-HT₁F Agonists (e.g., Lasmiditan): For those with contraindications to triptans.

- Antiemetics: Address nausea and vomiting, can provide rescue analgesic benefits.

- Prophylactic

- Beta-Blockers (e.g., Propranolol, Timolol, Metoprolol): First-line, especially with comorbid hypertension.

- Anticonvulsants (e.g., Valproate, Topiramate): Effective in reducing attack frequency, watch for side effects.

- Antidepressants (e.g., Amitriptyline): Useful when mood/anxiety components coexist.

- CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies (e.g., Erenumab, Fremanezumab): Targeting CGRP for moderate to severe frequent migraines.

- Botulinum Toxin A: Chronic migraine prophylaxis, especially if medication-based prophylaxis fails.

- Others: Verapamil, Candesartan, Riboflavin, Magnesium, etc.

Conclusion

Migraine pharmacotherapy demands a personalized, stepwise approach integrating both acute and prophylactic strategies. Substantial progress in understanding migraine pathophysiology—from trigeminal nerve activation and cortical spreading depression, through the role of CGRP—has propelled the development of more targeted, efficacious, and better-tolerated interventions.

For acute migraine attacks, the mainstay remains Triptans, combined with adjunctive antiemetics, NSAIDs, or newer classes like Gepants. Prophylaxis can be guided by factors such as comorbid conditions, side-effect profiles, and patient preferences. Common prophylactic agents include Beta-blockers, Topiramate, Valproate, and Amitriptyline, though the advent of CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibodies has opened a new therapeutic era for refractory or frequent migraineurs.

Key for success is patient education, addressing medication overuse, and ensuring adequate follow-up to adjust therapy as clinical and lifestyle factors evolve. Innovations such as Rimegepant for dual acute and prophylactic use, plus cutting-edge research on non-invasive neuromodulation, signal even more refined approaches in the future. By aligning treatment selection with individualized needs, clinicians can significantly lessen the burden of migraine and enhance patients’ day-to-day functioning and quality of life.

References

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13th Edition

- Katzung BG, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 15th Edition

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology, 8th Edition