Introduction

Among the modern arsenal of antibiotics, linezolid occupies a key position in the management of drug-resistant Gram-positive infections. Approved by the U.S. FDA in 2000, linezolid heralded the first-in-class oxazolidinone family of antibacterials, providing clinicians with a vital alternative to treat resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), and certain resistant strains of Streptococcus. Over the past two decades, its unique mode of action, favorable pharmacokinetic profile, and oral bioavailability have rendered it a mainstay in combating severe hospital and community-acquired infections that have eluded more conventional therapies.

Nevertheless, the widespread integration of linezolid has not been without concerns: the emergence of linezolid-resistant organisms, the potential for serious hematological or neurologic toxicities, and the need for judicious prescription to prolong its clinical utility. In this comprehensive, SEO-optimized overview, we will examine every aspect of linezolid’s pharmacology—its discovery and chemical structure, mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, therapeutic indications, adverse effect profile, drug interactions, resistance mechanisms, clinical pearls, and future directions. References will include “Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics” (13th Edition), “Katzung BG, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology” (15th Edition), and “Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology” (8th Edition).

Historical Background and Chemical Classification

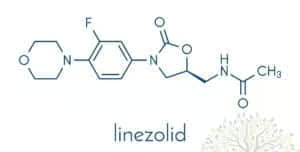

Linezolid represents the prototypical agent of the oxazolidinone class, which emerged from research efforts seeking novel chemical scaffolds that targeted bacterial protein synthesis. Unlike older antibiotic families such as beta-lactams, macrolides, or aminoglycosides, the oxazolidinones introduced a novel synthetic ring system—a 2-oxazolidinone moiety essential for antibacterial action. Early synthesis attempts in the 1980s and 1990s led to multiple derivatives, with linezolid eventually achieving clinical success due to a wide spectrum against Gram-positive cocci, negligible cross-resistance with older drug classes, and activity even against certain Gram-positive organisms harboring advanced resistance mechanisms.

Chemically, linezolid is characterized by an aryl ring attached to the 2-oxazolidinone nucleus. This structure is critical both for binding to the bacterial ribosome and for achieving an adequate pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profile. Variants of oxazolidinones continue to be investigated for expanded coverage or improved safety, affirming linezolid’s role as a blueprint for subsequent analogs (e.g., tedizolid, an advanced successor).

Mechanism of Action

Binding to the 50S Ribosomal Subunit

Linezolid exerts a bacteriostatic effect primarily against Gram-positive organisms by inhibiting the initiation phase of protein synthesis. It achieves this by:

- Targeting the Peptidyl Transferase Center (PTC)

- Linezolid binds near the 50S subunit’s P site of the bacterial ribosome.

- This binding blocks formation of the 70S initiation complex, essential for translation elongation.

- Prevention of fMet-tRNA Positioning

- Specifically, linezolid hinders the correct positioning of the fMet-tRNA complex at the P site, thereby aborting nascent peptide chain formation.

- This is unlike macrolides or lincosamides, which typically interfere with elongation or translocation steps.

Bacteriostatic vs. Bactericidal Activity

While linezolid is primarily bacteriostatic against most Gram-positive cocci, in some circumstances—particularly in certain Streptococcal species—it may exhibit mild bactericidal activity. However, in life-threatening infections (e.g., S. aureus pneumonia or complicated MRSA bacteremia), it is often used in combination or after weighing alternatives that offer more potent bactericidal action. Nonetheless, linezolid’s unique binding site and minimal cross-resistance with other protein synthesis inhibitors make it indispensable for difficult Gram-positive pathogens.

Spectrum of Activity

Linezolid is predominantly active against Gram-positive bacteria, including:

- Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA (methicillin-resistant) and some strains with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin (VISA/hVISA).

- Staphylococcus epidermidis and other coagulase-negative staphylococci, especially those resistant to multiple drug classes.

- Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium, including vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE).

- Streptococcus pneumoniae, including penicillin-resistant strains, and various viridans streptococci.

- Certain Corynebacterium species and Listeria monocytogenes.

However, linezolid generally lacks robust coverage against Gram-negative bacteria, as efflux pumps or intrinsic permeability barriers hamper its accumulation. Consequently, it is not indicated for Gram-negative infections. In addition, atypical or anaerobic coverage is modest compared to other classes. Clinicians thus harness linezolid’s potent Gram-positive spectrum in synergy with other agents when broader coverage is required.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

An important advantage of linezolid is its high oral bioavailability, exceeding 90%. Oral and IV doses are essentially interchangeable on a 1:1 mg basis, simplifying transitions from hospital to outpatient settings. Peak plasma concentrations are generally reached within 1–2 hours post-ingestion. Food may slightly delay absorption but does not significantly reduce the overall bioavailability, permitting flexible dosing relative to meal times.

Distribution

Linezolid demonstrates extensive tissue penetration, traveling widely in well-perfused organs, alveolar lining fluid, and intracellular compartments. It crosses into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) effectively, making it a valuable alternative for CNS infections caused by resistant Gram-positive cocci (e.g., meningitis due to VRE). Plasma protein binding is moderate (roughly 30%), ensuring a substantial free fraction available to exert antimicrobial activity in peripheral compartments.

Metabolism and Elimination

Metabolism occurs largely via oxidation of the morpholine ring, yielding two primary inactive metabolites excreted renally. Approximately 30% of an administered dose is excreted unchanged in the urine. The half-life of linezolid averages 5–7 hours, supporting a twice-daily (BID) regimen for most indications. Dose adjustments are typically unnecessary in mild-to-moderate renal or hepatic impairment. In severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, clinical judgment is essential, with potential monitoring of drug levels or usage of alternative therapies.

Pharmacodynamics

Time-Dependent Killing

Like numerous other bacteriostatic agents, linezolid demonstrates time-dependent killing. The efficacy correlates with the duration that plasma concentrations remain above the organism’s minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Prolonging the fT>MIC (fraction of time above MIC) is more predictive of clinical success than achieving high peak concentrations.

AUC/MIC Considerations

Nevertheless, AUC/MIC (area under the concentration-time curve over MIC) also serves as a significant predictive parameter. Adequate daily linezolid exposure ensures inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis. Loading doses are generally unnecessary, but consistent dosing intervals maintain therapeutic levels.

Post-Antibiotic Effect

While some agents display a post-antibiotic effect (PAE) that sustains bacterial suppression after subtherapeutic levels, linezolid’s PAE is moderate. Clinically, the standard BID regimen is effective, but certain pathogens or complicated infections might benefit from continuous or extended infusion strategies, though these are not standard.

Clinical Indications

Nosocomial and Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Linezolid is indicated for pneumonia caused by MRSA or penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae. Notably, in hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) with MRSA involvement, linezolid competes with vancomycin as a first-line agent. Some evidence suggests improved lung penetration relative to vancomycin, possibly giving it an advantage in severe pneumonia, though definitive consensus varies among guidelines.

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections (SSTIs)

Clinical trials reveal robust efficacy against complicated and uncomplicated SSTIs, including those caused by MRSA. Because linezolid can be administered orally with excellent bioavailability, it is an attractive choice for outpatient management of resistant staphylococcal cellulitis or abscesses once patients are hemodynamically stable.

Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Infections

In patients with VRE (especially E. faecium) bacteremia, endocarditis, or urinary tract infections, linezolid provides a potent oral and IV option. It is often used when alternatives like daptomycin or tigecycline are either unsuitable or have failed. Though synergy with aminoglycosides is less commonly pursued in VRE scenarios, combination therapy may be considered in endocarditis or complicated infections.

Other Potential Uses

- MDR-TB (Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis): While not first-line, linezolid is sometimes enlisted in salvage regimens for highly resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Nocardia or certain Mycobacteria (non-tuberculous species) may also respond to linezolid.

- Off-Label usage in select bone/joint infections or CNS infections by Gram-positive pathogens resistant to standard therapy.

Adverse Effects

Hematologic Toxicities

Bone marrow suppression stands out as a principal concern, with thrombocytopenia being the most frequent manifestation. Anemia and neutropenia can also occur. Risk factors include:

- Longer Duration of Therapy (usually beyond two weeks).

- Preexisting Bone Marrow Dysfunction.

- Renal Impairment, as reduced clearance of metabolites might intensify toxicity.

Periodic complete blood counts (CBC) are advised, especially for courses extending beyond 10–14 days.

Mitochondrial Toxicity

Prolonged linezolid use has been linked with lactic acidosis and peripheral neuropathy or optic neuropathy, pointing to possible inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis. The risk is heightened with exposures longer than four weeks. These neuropathies can be irreversible if not recognized early.

Serotonin Syndrome

Given that linezolid partially inhibits monoamine oxidase A and B, concurrent use with serotonergic agents (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs, MAO inhibitors) can precipitate serotonin syndrome—a potentially life-threatening condition characterized by hyperthermia, autonomic instability, and neuromuscular abnormalities. Clinicians must exercise caution:

- Monitoring for signs of confusion, agitation, tachycardia, hyperreflexia.

- Avoid or temporarily discontinue serotonergic medications if feasible.

Gastrointestinal and Other Effects

- Diarrhea, nausea, headache, and taste alterations are relatively common but typically mild.

- Rash or allergic reactions can occur but are less prevalent than with some beta-lactams or sulfonamides.

- Elevation in Liver Enzymes is occasionally noted, warranting hepatic monitoring if clinically indicated.

Drug Interactions

Serotonergic Agents and MAO Inhibition

As noted, the partial MAO inhibition by linezolid makes it hazardous to combine with:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) like paroxetine or sertraline.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants, sympathomimetics, or any agent with serotonergic or adrenergic effects.

- MAO Inhibitors: The combination is typically contraindicated to avoid hypertensive crises or severe serotonin syndrome.

Pseudoephedrine, Phenylpropanolamine

Sympathomimetics or vasopressors may combine with linezolid’s mild MAO inhibition to raise blood pressure or produce hypertensive episodes, so dose caution or avoidance is recommended.

Rifampin

Rifampin induces hepatic enzymes that can accelerate linezolid metabolism, though the clinical significance remains uncertain. Some data indicate decreased linezolid exposure in co-administration, urging close therapeutic drug monitoring (if available) or alternative choices to ensure efficacy.

Resistance Mechanisms

Over time, certain organisms have developed or acquired resistance to linezolid:

- Mutation in 23S rRNA

- The most common mechanism involves point mutations in domain V of the 23S rRNA within the 50S subunit, reducing linezolid binding affinity.

- Pathogens can harbor multiple rRNA copies, with progressive accumulation of mutated copies conferring higher resistance levels.

- Cfr Methyltransferase

- This gene, discovered initially in staphylococci, methylates an adenine in 23S rRNA, preventing linezolid from binding effectively.

- The cfr gene also impacts the binding of other classes like phenicols and lincosamides, signifying multi-drug resistance.

- Overuse and Prolonged Therapy

- Inappropriate prescribing fosters selective pressure for resistant mutants.

- Poor infection control in hospitals accelerates spread of linezolid-resistant staphylococci or enterococci.

To mitigate resistance development, conservative usage—limited to confirmed resistant Gram-positive pathogens—and robust antimicrobial stewardship programs remain critical.

Clinical Efficacy: Studies and Comparative Data

Multiple randomized trials and meta-analyses have assessed linezolid efficacy:

- MRSA Pneumonia: Some studies suggest linezolid may yield higher clinical cure rates and better lung penetration than vancomycin, though results have been mixed, prompting debate among guidelines.

- Complicated Skin Infections: Trials indicate non-inferiority or mild superiority over comparators like vancomycin or teicoplanin, particularly for outpatient therapy.

- VRE: Clinical outcomes in VRE bacteremia or complicated UTIs generally favor linezolid with decent cure rates, establishing it as a mainstay second-line or salvage agent if daptomycin is contraindicated.

However, cost and toxicity considerations often necessitate thorough benefit-risk assessments before choosing linezolid over older, more established therapies.

Dosage and Administration

Standard Regimen

For adults with complicated SSTIs or pneumonia, the recommended dose of linezolid is typically:

- 600 mg IV or orally every 12 hours.

- Duration ranges from 10–14 days in pneumonia or complicated SSTIs.

- Extended courses (up to 28 days) may be used in osteomyelitis, endocarditis, or persistent infections, with close adverse effect monitoring.

Special Populations

- Pediatrics: Dosing is weight-based (e.g., 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for children up to 12, adjusting for age/weight). Monitoring for bone marrow suppression is crucial.

- Renal/Hepatic Impairment: No absolute dose adjustment is mandated, though caution is warranted, especially in advanced disease.

- Elderly: Same adult dosing typically applies, mindful of heightened risk for myelosuppression.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

While not universally available, TDM for linezolid can be performed in specialized centers, particularly in managing severe or persistent infections, or in patients at high risk for toxicity (e.g., end-stage renal disease). Maintaining trough concentrations below certain thresholds (e.g., < 10 mg/L) may reduce the likelihood of adverse hematologic or neurologic events.

Practical Clinical Pearls

- Oral to IV Transition: Seamless switch at the same dose fosters continuity of care and cost savings.

- Baseline Labs: CBC, including platelets, recommended prior to therapy.

- Weekly CBC Monitoring: If therapy extends beyond 14 days, watch for dropping platelets or WBC, adjusting therapy accordingly.

- Evaluate Neurologic Complaints: Consider linezolid cessation if peripheral or optic neuropathy manifest.

- Assess Concomitant Drugs: Especially SSRIs or MAOIs, to prevent severe serotonin toxicity.

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages

- Excellent Oral Bioavailability: Simplifies outpatient regimens.

- Rigid Gram-Positive Coverage: Targets resistant staphylococci and enterococci.

- Penetration: Good distribution in lung tissue, bone, and CNS.

- Low Cross-Resistance: Novel binding site spares cross-resistance with most older classes.

Limitations

- Cost: Historically quite expensive, though generics have improved affordability somewhat.

- Toxicity: Myelosuppression and neuropathy with extended use.

- MAO Inhibition: Risk of serotonin syndrome or drug interactions.

- Mostly Bacteriostatic: Not always ideal for serious endovascular or immunocompromised infections requiring strong bactericidal therapy.

Emerging Alternatives and Future Directions

Next-Generation Oxazolidinones

Tedizolid, another oxazolidinone, has garnered attention for possibly less myelotoxicity, a once-daily regimen, and some inherent activity against certain linezolid-resistant strains. Additional research explores novel modifications to bypass cfr-mediated or rRNA mutation-based resistance.

Combination Strategies

In cases of complex MRSA pneumonia or severe bloodstream infections, synergy with rifampin, daptomycin, or beta-lactams has been investigated, aiming to heighten bactericidal effects or mitigate resistance. However, robust clinical data remain limited, necessitating individualized decisions.

Minimizing Toxicities

Research into therapeutic drug monitoring, shortened therapy durations (e.g., 5-day regimens for certain skin infections), or co-administration of protective agents (like antioxidant supplements to reduce mitochondrial stress) remains ongoing. The overarching goal is retaining linezolid’s efficacy while lessening side effects that hamper its long-term usage.

Conclusion

Linezolid stands as a pivotal solution to modern antibiotic resistance challenges in Gram-positive infections. By hindering the formation of the bacterial 70S initiation complex, it effectively addresses MRSA, VRE, and multi-resistant staphylococcal or streptococcal pathogens. Its high oral bioavailability, consistent tissue penetration (including lung and CNS compartments), and minimal cross-resistance with older agents have made it indispensable for severe or complicated infections.

Accompanying these benefits, however, are major caveats: linezolid’s potential to induce myelosuppression, neuropathy, and serotonin syndrome underscores the importance of vigilant patient monitoring, especially in extended courses. Careful selection, short durations when feasible, and integration into comprehensive antimicrobial stewardship programs help preserve linezolid’s valuable activity.

While emergent therapies (e.g., tedizolid) promise incremental improvements in safety and coverage, linezolid remains integral for bridging the gap against recalcitrant Gram-positive infections in both inpatient and outpatient scenarios. Its unique place within the antibiotic armamentarium—and the lessons learned from its introduction and subsequent usage—extend a vital roadmap for addressing antibiotic resistance in the 21st century.

Book Citations

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13th Edition.

- Katzung BG, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 15th Edition.

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology, 8th Edition.