Introduction

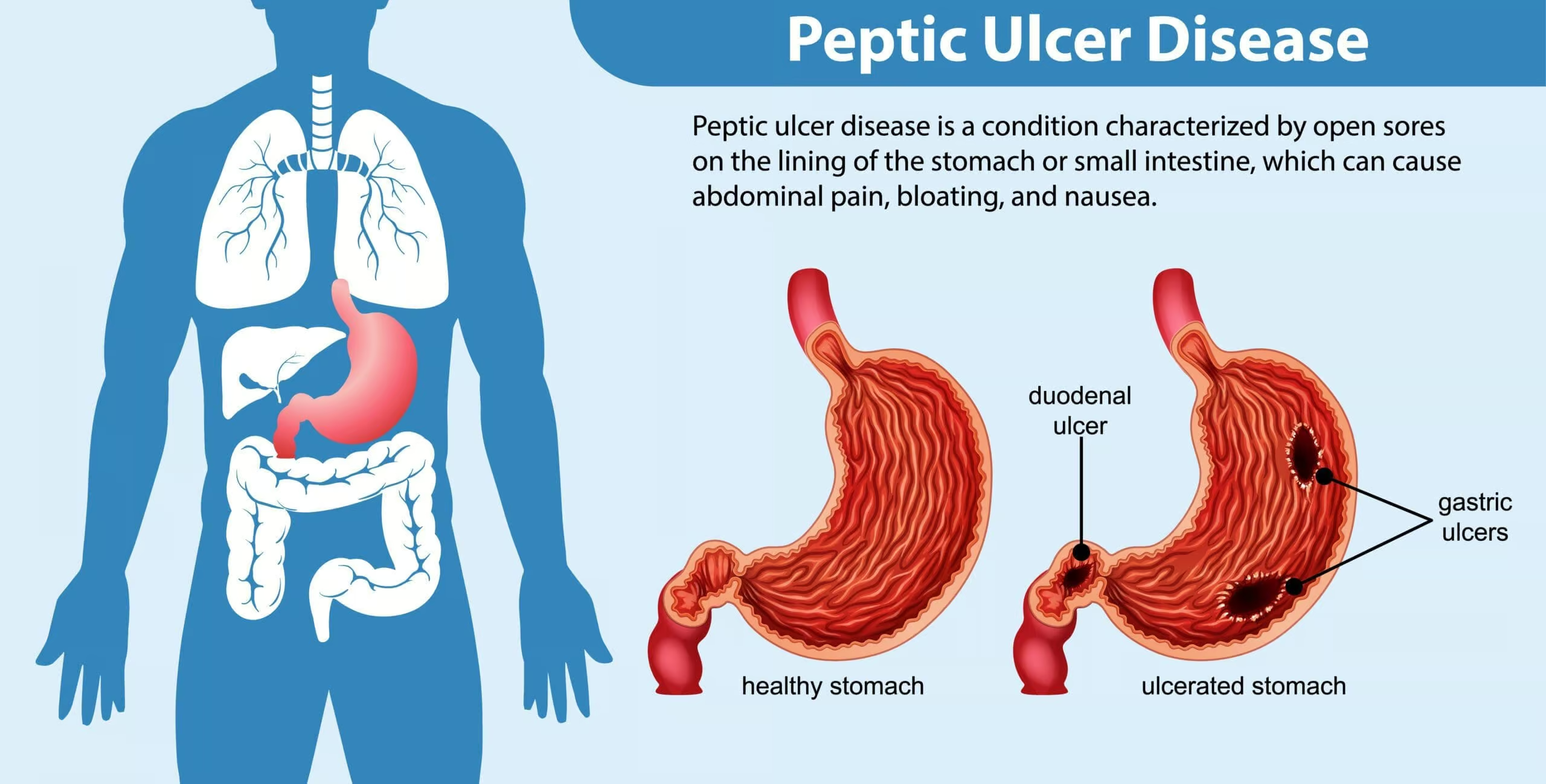

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) encompasses the formation of ulcers in the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (duodenal ulcer), primarily caused by gastric acid hypersecretion and/or compromised defense of the gastric and duodenal mucosa. While Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection remains a principal etiology for many cases, other contributing factors include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), stress-related mucosal injury, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma). Clinically, patients may present with epigastric pain, dyspepsia, bloating, and occasionally alarming symptoms such as upper GI bleeding (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

The management of peptic ulcer disease hinges on a combination of pharmacological therapies aimed at (1) eradicating H. pylori if present, (2) suppressing gastric acid secretion or neutralizing it, (3) protecting the gastric mucosal barrier, and (4) concurrently addressing any risk factors such as NSAID use. Over the past several decades, the advent of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and enhanced understanding of H. pylori have revolutionized peptic ulcer management, reducing morbidity, lowering recurrence rates, and often eliminating the need for surgery. This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern pharmacotherapy for peptic ulcers, highlighting the core drug classes, their mechanisms, and the clinical strategies for optimizing treatment outcomes (Katzung, 2020).

Pathophysiology of Peptic Ulcer Disease

An ulcer arises when the aggressive influences of gastric acid, pepsin, and potential toxins outweigh the defensive mechanisms of the mucosal barrier, bicarbonate production, epithelial cell renewal, and adequate blood supply. Key triggers or risk factors include:

- H. pylori: This gram-negative bacterium colonizes the gastric epithelium, disrupting the mucosal barrier, increasing acid secretion (especially in duodenal ulcers), and inciting chronic inflammation.

- NSAIDs: By inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis (via the COX-1 pathway), NSAIDs diminish mucosal defenses such as bicarbonate and mucus production and reduce mucosal blood flow, predisposing to ulceration.

- Hypersecretory States: Rare conditions like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma) induce markedly high levels of gastric acid, overwhelming mucosal defenses.

- Lifestyle: Smoking, high alcohol intake, and stress can exacerbate mucosal injury or impair healing (Rang & Dale, 2019).

In the modern era, diagnosing and addressing H. pylori infection are cornerstones of PUD management. Moreover, acid-suppressive treatments, such as H2 blockers and PPIs, have drastically improved healing rates. Understanding the interplay of acid secretion, mucosal repair, and potential bacterial involvement permits targeted and effective pharmacological interventions (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Diagnosis and Therapeutic Goals

Before initiating targeted therapy, diagnosing peptic ulcer disease often involves endoscopy or non-invasive tests (urea breath test, stool antigen test for H. pylori). Once an ulcer is confirmed, treatment pursuits include:

- Eradication of H. pylori: to prevent ulcer recurrence and reduce gastric cancer risk.

- Neutralization or reduction of acid secretion: to enhance symptom relief and facilitate ulcer healing.

- Protection of the gastric mucosa: to strengthen the defensive barrier and accelerate lesion repair.

- Elimination or reduction of modifiable risk factors (e.g., cessation of NSAIDs, smoking cessation) (Katzung, 2020).

Ultimately, successful therapy should yield symptom resolution, mucosal healing (as confirmed by endoscopy for complicated ulcers), prevention of rebleeding, and minimal adverse effects or treatment burdens for patients.

Eradication of H. pylori

Background on H. pylori

H. pylori invades gastric epithelium and thrives in the acidic milieu by producing urease, generating ammonia and buffering its microenvironment. Its presence incites robust local immune responses, perpetuating inflammation and damaging the mucosa. Eradication significantly reduces ulcer relapse, making it a treatment priority (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Triple Therapy

Historically, the first-line approach to H. pylori was triple therapy, commonly administered for 14 days:

- Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI): e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole

- Clarithromycin

- Amoxicillin (or metronidazole if penicillin-allergic)

While often successful, rising clarithromycin resistance has impacted efficacy in many regions (Katzung, 2020).

Quadruple Therapy

Because of increasing antibiotic resistance, quadruple therapy frequently replaces or follows triple therapy in areas with high clarithromycin resistance:

- PPI

- Bismuth Subsalicylate

- Metronidazole (or tinidazole)

- Tetracycline

This regimen, referred to as bismuth quadruple therapy, is typically given for 10–14 days and demonstrates robust eradication rates even amidst antibiotic resistance patterns (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Concomitant Therapy, Sequential Therapy, and Hybrid Regimens

Other regimens—concomitant therapy (PPI + clarithromycin + amoxicillin + metronidazole) or sequential therapy (sequential antibiotic changes across a 10-day course)—may be employed depending on local resistance data and patient tolerance. In general, compliance is pivotal; incomplete regimens or missed doses favor antibiotic resistance and eventual treatment failure (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Salvage or Rescue Treatments

Patients who fail conventional first-line or second-line eradication may require rescue therapies using different antibiotic choices—e.g., levofloxacin-based triple therapy, rifabutin, or high-dose dual therapy with PPI plus amoxicillin if multiple antibiotic resistances exist (Katzung, 2020).

Acid-Suppressive Therapies

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

Mechanism of Action

Proton pump inhibitors—including omeprazole, esomeprazole, rabeprazole, lansoprazole, and pantoprazole—irreversibly inhibit the H+/K+ ATPase enzyme (the proton pump) at the parietal cell’s secretory canaliculi. As a consequence, they effectively block the final common step in gastric acid secretion, producing a marked and prolonged reduction in acid output (Katzung, 2020).

Pharmacokinetics and Dosing

Because PPIs are prodrugs requiring activation within acidic compartments, they are best administered 30–60 minutes before a meal. Their elimination half-lives range from 0.5–2 hours, but the effect on acid secretion persists significantly longer, typically up to 24 hours, due to the irreversible nature of parietal cell pump binding (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Indications

- Peptic ulcer disease: PPIs accelerate ulcer healing, especially beneficial for NSAID-related ulcers.

- H. pylori eradication regimens (combined with antibiotics).

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma) (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Adverse Effects and Considerations

Long-term PPI use is generally safe, but potential issues include:

- Malabsorption: Reduced gastric acidity may impair vitamin B12, iron, or other micronutrients absorption.

- Osteoporosis Risk: Chronic high-dose therapy might predispose to decreased calcium absorption and bone density loss.

- Clostridium difficile Infection: Lowered gastric acid can allow certain pathogens to flourish.

- Drug Interactions: e.g., Omeprazole can affect clopidogrel conversion (particularly if a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer or a strong inhibitor is used).

Monitoring the duration of therapy and periodically reassessing the need for continued PPIs can mitigate such risks (Katzung, 2020).

Histamine-2 (H2) Receptor Antagonists

Mechanism of Action

H2 receptor antagonists—such as ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and (historically) cimetidine—work by blocking the H2 receptors on gastric parietal cells, reducing histamine-stimulated acid release. They typically produce less potent inhibition of acid secretion compared to PPIs, particularly for nocturnal acid production (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Clinical Uses

Before PPIs dominated, H2 antagonists were the main acid-suppressive agents for peptic ulcer disease. They remain viable in mild to moderate disease, prophylaxis of stress ulcers in hospitalized patients, or for patients who experience intolerance to PPIs. They can also be used in combination with other agents in H. pylori regimens, though less frequently so in modern practice (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Adverse Effects

- Tolerance: Tachyphylaxis can develop with H2 blockers if used for prolonged periods, reducing effectiveness.

- Drug Interactions: Cimetidine is a notorious inhibitor of CYP450 enzymes, raising levels of warfarin, theophylline, and other drugs. Newer agents (e.g., famotidine) present fewer interactions.

- Central Nervous System effects (e.g., confusion, dizziness) reported in the elderly, especially with IV administration of H2 blockers (Katzung, 2020).

Antacids

Mechanism and Types

Antacids—often contain aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide, calcium carbonate, or a combination—neutralize gastric acid, thereby reducing heartburn and symptomatic acidity. Although they do not directly heal ulcers or reduce acid secretion from parietal cells, they provide rapid, short-lived symptomatic relief (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Role in Peptic Ulcer Disease

Historically, high-dose antacid regimens were used to heal peptic ulcers, but with the advent of H2 antagonists and PPIs, their role is now primarily adjunctive for immediate symptom control. They may be beneficial between PPI doses or for on-demand relief in mild dyspepsia (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Adverse Effects

- Aluminum hydroxide: Tends to cause constipation.

- Magnesium hydroxide: Can lead to diarrhea.

- Calcium carbonate: Rebound acid secretion and hypercalcemia in very high doses.

- Sodium bicarbonate: Potential for metabolic alkalosis if used excessively.

Balancing combinations (e.g., aluminum plus magnesium) can mitigate stool disturbances (Katzung, 2020).

Mucosal Protective Agents

Sucralfate

Sucralfate forms a viscous, cross-linked polymer in acidic environments that adheres to ulcer craters, creating a physical barrier against acid, pepsin, and bile salts. This local protection promotes healing and reduces further tissue injury.

- Clinical Use: Primarily beneficial in hospitalized patients or those who cannot tolerate PPIs or H2 antagonists. Requires acidic pH to activate, so concurrent antacid or PPI usage can reduce its efficacy (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

- Adverse Effects: Minimal systemic absorption, but the aluminum base can contribute to constipation and, rarely, elevated aluminum levels in renal impairment.

Bismuth Compounds

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) or bismuth subcitrate potassium acts similarly by coating the ulcer base, enhancing prostaglandin and mucus secretion, and possessing some antimicrobial properties against H. pylori. Bismuth is featured in quadruple therapy for H. pylori eradication.

- Adverse Effects: Darkening of tongue or stool (harmless), possible salicylate toxicity if used excessively (Katzung, 2020).

Prostaglandin Analogues: Misoprostol

Misoprostol is a synthetic PGE1 analog that stimulates mucus and bicarbonate production while decreasing acid secretion. It is particularly beneficial in preventing NSAID-induced ulcers.

- Adverse Effects: Diarrhea, abdominal cramps, uterine contractions (contraindicated in pregnancy due to risk of miscarriage).

- Clinical Use: Typically restricted to high-risk NSAID users (e.g., older patients, history of ulcer complications). The side effect burden often limits widespread adoption (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

NSAID-Related Peptic Ulcers

Mechanistic Insights

NSAIDs can trigger ulcers by inhibiting COX-1–derived prostaglandins that normally protect the gastric mucosa. Chronic NSAID use thus erodes mucosal defenses, leading to superficial erosions or deeper ulcers (Katzung, 2020).

Strategies for Prevention

- Minimize or Discontinue NSAIDs: If feasible, switch to acetaminophen or COX-2 selective inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) that spare COX-1.

- Co-therapy with PPIs: For patients requiring chronic NSAIDs (e.g., rheumatic diseases), concurrent PPI can significantly reduce the risk of ulcers and GI bleeding.

- Misoprostol Adjunct: In high-ulcer–risk individuals, misoprostol plus an NSAID can mitigate gastric damage. However, GI side effects hamper routine use (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Treatment of Established NSAID Ulcers

• If NSAIDs can be discontinued, standard PPI therapy for 4–8 weeks suffices to heal most ulcers.

• If NSAIDs must continue, a PPI is the most effective acid suppression measure, combined with potential substitution of a lower GI-risk NSAID or a partially selective COX-2 inhibitor (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES)

Key Features

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome involves a gastrin-secreting tumor (gastrinoma) often found in the duodenum or pancreas, leading to excessive gastric acid production, refractory or multiple ulcers, and diarrhea. These patients require high-dose or continuous acid suppression, frequently with PPIs (Katzung, 2020).

Pharmacological Management

- High-Dose PPIs: e.g., omeprazole 60–120 mg/day in divided doses or intravenous pantoprazole for acute bleeding.

- Surgery or somatostatin analog (octreotide) in certain cases to control gastrin release or if the tumor is resectable.

- Lifelong therapy is often needed unless the gastrinoma can be surgically removed or cured (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Stress-Related Mucosal Damage

Pathogenesis

Critically ill patients (e.g., in the ICU) may develop stress ulcers from reduced splanchnic blood flow and compromised mucosal defenses. Risk escalates with mechanical ventilation, coagulopathy, shock, or severe trauma/burns (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Prophylaxis

Prophylactic PPIs or H2 blockers are often given to high-risk ICU patients to ward off stress-related erosions and possible GI bleeding. Surplus prophylaxis in low-risk patients, however, is being reconsidered due to infection concerns (particularly pneumonia and Clostridium difficile) (Katzung, 2020).

Management of Bleeding Stress Ulcers

For significant hemorrhage, endoscopic evaluation, intravenous PPI infusion, and supportive measures (transfusion, volume resuscitation) help stabilize patients, with prophylaxis continuing afterward as indicated (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Clinical Approach to Pharmacotherapy

Stepwise Management for Non-Complicated Ulcers

- Identify H. pylori: If positive, commence eradication therapy (triple or quadruple).

- Start Acid-Suppressive: Typically a PPI for 4–8 weeks accelerates healing.

- Assess NSAID Use: Discontinue or reduce if possible; otherwise, add prophylactic PPI.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Smoking cessation, limit alcohol, dietary adjustments for symptom relief.

Complicated Ulcers

- For bleeding peptic ulcers or suspected perforation, endoscopic intervention plus IV PPI infusion is often required.

- Prolonged maintenance acid suppression can be considered for patients with recurrent bleeding or severe comorbidities.

Follow-Up and Confirmation

- Test of Cure for H. pylori after eradication therapy (urea breath test or stool antigen test) ensures success; a repeated endoscopy for high-risk patients verifies complete ulcer healing (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Safety Profile and Monitoring

Long-Term PPI Monitoring

While PPIs remain indispensable for peptic ulcer control, vigilance regarding potential complications of prolonged therapy—osteoporosis, renal issues, C. difficile risk, micronutrient malabsorption (B12, magnesium)—is essential. Careful stepping down or attempting off-therapy once the ulcer is healed can curb unnecessary long-term use (Katzung, 2020).

Interactions and Adjustments

- CYP450 Interactions: Some PPIs (e.g., omeprazole) can alter metabolism of warfarin, phenytoin, diazepam, and clopidogrel.

- Kidney/Liver Dysfunction: Dose adjustments for H2 blockers (e.g., ranitidine, famotidine) may be needed in renal impairment to prevent overaccumulation.

- Allergic Reactions: Rare but notable, especially with antibiotic components of H. pylori regimens (penicillin or clarithromycin allergies, for instance) (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Future Directions and Investigational Agents

Novel Antibiotics for H. pylori

With antibiotic resistance on the rise, investigations into new agents (e.g., rifabutin combination rescue therapies, fluoroquinolone-based quadruple regimens) aim to preserve high eradication rates. Research into vaccines or immunomodulatory approaches to H. pylori remain ongoing but not yet clinically implemented (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers (P-CABs)

Vonoprazan belongs to a new class of potassium-competitive acid blockers that can rapidly and potently inhibit the parietal cell proton pump in a reversible manner. Potential advantages include faster onset compared to traditional PPIs and more consistent acid control, even with once-daily dosing. Already in use in some regions (e.g., Japan), P-CABs could expand worldwide if longer-term safety data is favorable (Katzung, 2020).

Regenerative and Protective Strategies

Studies examining growth factors, cytokine modulators, or agents that enhance mucosal repair could help treat complicated ulcers or patients struggling with healing on current regimens. Probiotics and dietary modifications might also complement standard therapy by reinforcing mucosal defenses (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Special Populations

Pediatrics

Peptic ulcers in children are less common but can occur with H. pylori, chronic NSAID use, or congenital anomalies. Pediatric dosing strategies rely on weight-based calculations for PPIs and antibiotic regimens. Confirmed compliance and shorter therapy durations help with tolerability, but close follow-up is crucial (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Elderly

Elderly patients are more likely to be on polypharmacy, including chronic NSAIDs for arthritis or cardiovascular prophylaxis with low-dose aspirin. Additional caution is warranted to avoid potential drug-drug interactions, to monitor for renal and hepatic function changes, and to guard against PPI overuse, which can elevate pneumonia or fracture risks (Katzung, 2020).

Pregnancy

For pregnancy-related GERD or peptic ulcer flares, PPIs such as lansoprazole or H2 blockers like ranitidine are generally considered relatively safe if indicated. Antibiotic choices for H. pylori are more restricted—e.g., tetracyclines are contraindicated—requiring individualized risk-benefit assessments (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Cost-Effectiveness and Adherence

Economic Considerations

The cost of PPI therapy and multi-drug H. pylori regimens can be significant for patients lacking comprehensive insurance. Generics for PPIs, H2 blockers, and certain antibiotics can mitigate expenses. Additionally, performing thorough local antibiotic resistance surveillance helps tailor regimens that are both cost-effective and likely to succeed (Rang & Dale, 2019).

Strategies to Improve Compliance

- Simplified dosing schedules (e.g., once- or twice-daily regimens).

- Patient education regarding the importance of completing antibiotic courses.

- Tools like medication calendars, phone reminders, or blister packaging.

Poor adherence can lead to partial H. pylori eradication or ulcer relapse, highlighting the critical role of counseling and follow-up (Katzung, 2020).

Integrative Measures and Lifestyle

Dietary Advice

Although no rigid diet is universally mandated, reducing irritants such as spicy foods, caffeine, and alcohol may alleviate symptoms. Adequate hydration, regular meal patterns, and avoiding bedtime meals can also help.

Smoking Cessation

Smoking impairs mucosal blood flow, slows ulcer healing, and aggravates acid secretion. Encouraging cessation can bolster medication effectiveness and reduce recurrence risk (Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Stress Management

Prolonged stress can modulate immune and inflammatory pathways, potentially influencing ulcer susceptibility. While not the primary cause, addressing stress may enhance overall well-being and benefit compliance.

Summary of Key Medications and Their Roles

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, for potent and sustained acid suppression; backbone of therapy.

- H2 Receptor Antagonists: e.g., ranitidine, less potent acid suppression but useful in mild cases or maintenance therapy.

- Antacids: e.g., magnesium hydroxide, aluminum hydroxide, quick symptomatic relief, do not directly promote healing.

- Mucosal Protectants: Sucralfate, bismuth compounds, misoprostol (for NSAID-induced prophylaxis).

- H. pylori Eradication: Combination regimens include clarithromycin, amoxicillin or metronidazole, tetracycline, bismuth, and PPIs.

- NSAID Management: Evaluate necessity, add PPI or misoprostol, or switch to partially selective COX-2 inhibitors if possible.

- Rescue/Advanced: For refractory H. pylori, salvage antibiotic regimens; for hypersecretory states, high-dose PPI or P-CAB therapy (Rang & Dale, 2019; Katzung, 2020; Goodman & Gilman, 2018).

Conclusion

Pharmacotherapy for peptic ulcer disease has evolved over the last few decades from broad attempts at acid neutralization and partial inhibition to a highly targeted, evidence-based approach. Key breakthroughs—most notably the discovery of H. pylori and the development of proton pump inhibitors—have drastically improved healing rates and lowered recurrence. Contemporary practice demands careful identification of H. pylori infection, strategic application of antibiotic combination therapies, potent acid suppression (with PPIs leading the field), and reinforcement of mucosal defenses via agents like bismuth or misoprostol when indicated (Katzung, 2020).

Addressing and, where possible, modifying risk factors such as NSAID use or smoking are integral to both cure and relapse prevention. For the significant minority with complicated ulcers—bleeding, perforation, or malignancies—optimal therapy merges endoscopic interventions, IV PPI infusion, and persistent follow-up. As antibiotic resistance patterns change, guidelines must adapt, introducing quadruple or rescue regimens to sustain high eradication success (Goodman & Gilman, 2018). Meanwhile, new categories of acid suppressors, like potassium-competitive acid blockers, offer promising alternatives to conventional PPIs.

Overall, successful peptic ulcer management hinges on a comprehensive strategy: accurate diagnosis, potent acid suppression, eradication of H. pylori, protective measures against mucosal insult, patient lifestyle modifications, and vigilant monitoring. This multi-pronged approach ensures that most individuals with PUD can achieve lasting healing, enhanced symptom relief, and minimized risk of recurrences and complications (Rang & Dale, 2019).

References (Book Citations)

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13th Edition.

- Katzung BG, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 14th Edition.

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology, 8th Edition.