Executive Summary

The nomenclature of pharmaceutical agents is not merely a bureaucratic exercise in labeling; it is the foundational linguistic infrastructure of modern medicine. It serves as the critical interface between chemical innovation, regulatory oversight, clinical practice, and patient safety. From the precise molecular definitions required by synthetic chemists to the memorable brand names crafted for consumer recall, drug naming involves a complex, often contentious, interplay of hard science, international law, and psycholinguistics. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of drug nomenclature, tracing its evolution from the disorganized taxonomy of herbalism to the algorithmic complexities of naming monoclonal antibodies and gene therapies. It examines the pivotal roles of global bodies like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council, analyzes the geopolitical divergence regarding biosimilar suffixes, and details the cognitive safety mechanisms—such as Tall Man lettering—implemented to prevent catastrophic medication errors. By integrating data from foundational texts such as Goodman & Gilman’s, Katzung’s Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, and Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology, alongside contemporary regulatory guidance, this document offers a definitive reference for the professional understanding of how drugs are named, tracked, and regulated in a globalized economy.

1. Introduction: The Linguistic Architecture of Therapeutics

The history of pharmacology is, in many respects, a history of language. As humanity transitioned from the empiricism of herbalism to the precision of synthetic chemistry, the need to distinctively identify therapeutic agents became paramount. In the pre-scientific era, nomenclature was descriptive, mythological, or rooted in the physical appearance of a plant—names like “Foxglove” or “Nightshade” conveyed botanical origin but little about physiological action. Today, drug nomenclature is a highly regulated, scientifically rigorous process designed to ensure global harmonization and patient safety.

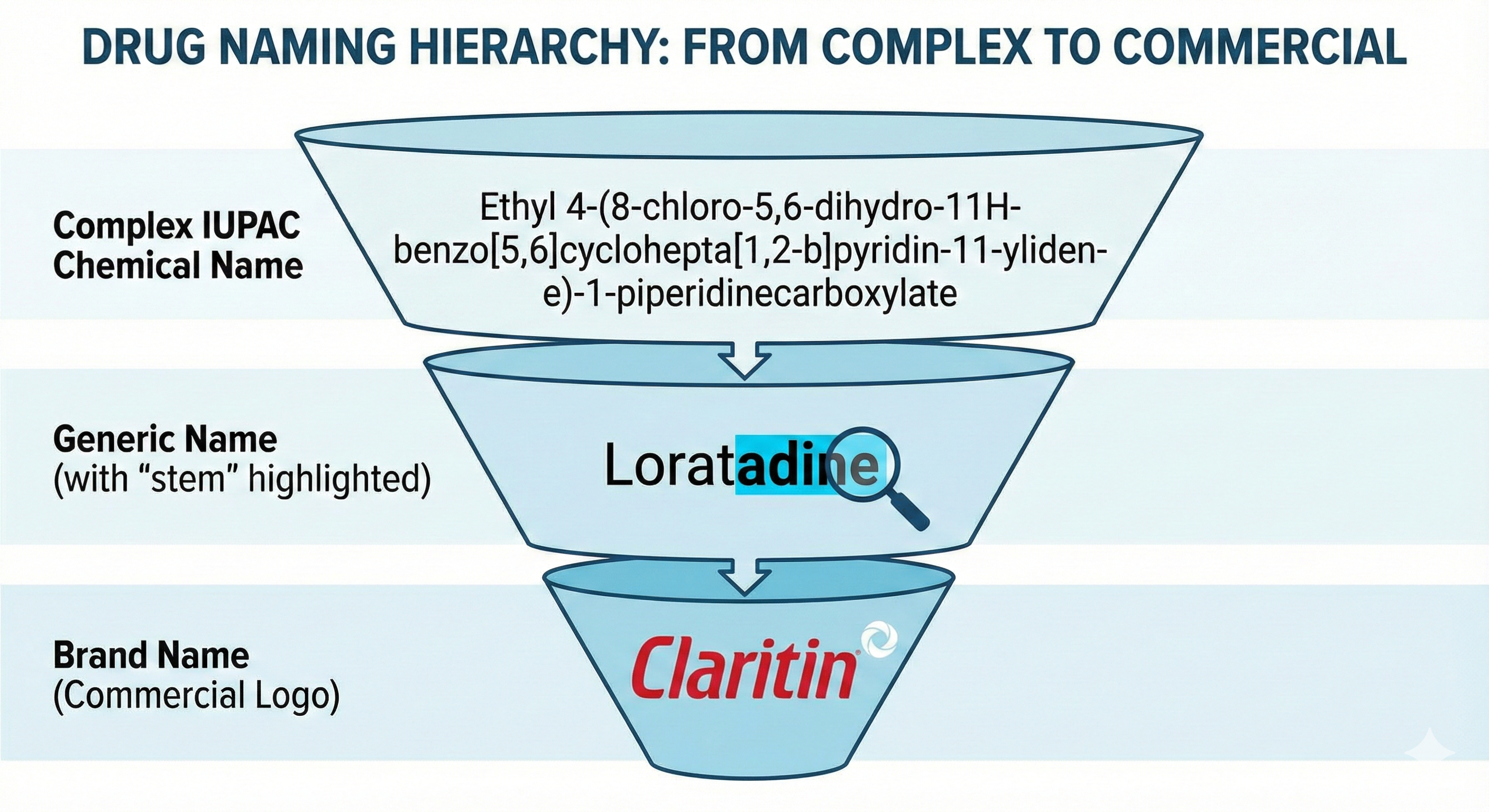

Modern drug nomenclature operates on three distinct, yet interconnected levels, each serving a specific audience and purpose:

- The Chemical Name: A rigorous description of the atomic structure, serving the needs of chemists and patent attorneys.

- The Generic (Nonproprietary) Name: The official identifier of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), serving the needs of regulators, researchers, and healthcare professionals.

- The Brand (Proprietary) Name: The commercial trademark, serving the needs of marketing, intellectual property protection, and consumer recognition.

1.1 The Imperative of Standardization

In a globalized pharmaceutical market, a single molecule may be synthesized in India, formulated in Germany, packaged in Brazil, and prescribed in Canada. Without a unified naming convention, the risk of duplicate therapies or missed drug interactions would be unmanageable. The World Health Organization (WHO) established the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) system in 1950 to address this very need, mandating that names be distinctive, sound-proof against confusion, and free from promotional claims. This move towards standardization was not merely administrative but a public health necessity, ensuring that a physician in Tokyo and a pharmacist in Toronto could communicate unambiguously about the same life-saving agent, regardless of the trade name printed on the box.

1.2 The Evolution of Drug Discovery and Naming

As outlined in Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, the paradigm of drug discovery has shifted from the isolation of natural products to the “invention” of new compounds through synthetic organic chemistry. This shift necessitated a nomenclature system capable of handling thousands of new molecular entities (NMEs). The early 20th century saw the rise of dye-based therapeutics—Paul Ehrlich’s “Salvarsan” (arsphenamine) famously signaled the hope of salvation from syphilis—but names were often ad-hoc. Today, naming is a pre-clinical milestone, occurring long before a drug reaches human trials, integrated into the very fabric of the drug development lifecycle to ensure that by the time a drug reaches the market, its identity is established, protected, and harmonized.

2. The Anatomy of a Drug Name: Chemical, Generic, and Proprietary

To understand the complexity of pharmaceutical nomenclature, one must dissect the three distinct identities assigned to every approved medication. These identities function like a funnel, moving from extreme specificity and complexity to simplified utility and finally to commercial distinctiveness.

2.1 The Chemical Name: The Scientist’s Blueprint

The chemical name is the first identity a drug possesses. It is a rigorous scientific description of the drug’s atomic and molecular structure, adhering to the rules established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

- Structure and Function: Chemical names provide a complete map of the molecule. For example, the chemical name for the common analgesic paracetamol (acetaminophen) is N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acetamide. For more complex molecules, these names can become paragraph-long strings of alphanumeric descriptors that are impossible to use in clinical conversation.

- Stereochemistry and Precision: Chemical naming must account for stereoisomerism—the spatial arrangement of atoms. Prefixes such as (R)- or (S)-, and cis- or trans-, are critical. For instance, the chemical name for ibuprofen includes the designation (RS)-2-(4-(2-methylpropyl)phenyl)propanoic acid, indicating it is a racemic mixture. This precision is vital because enantiomers can have vastly different pharmacological effects (e.g., the tragedy of thalidomide, where one enantiomer was teratogenic).

- Utility and Limitations: While essential for chemists to synthesize the compound and for patent attorneys to define the novelty of a claim, chemical names are discarded in clinical practice due to their unwieldiness. They serve as the “source code” of the drug, while the generic name serves as the “user interface.”

- Complexity Trends: As drug discovery moves towards larger molecules and macrocycles, chemical names are becoming increasingly complex. This trend underscores the necessity of the simplified generic nomenclature systems.

2.2 The Generic Name: The Global Standard

The generic, or nonproprietary, name is the official identifier of the drug substance. It is “public property,” meaning it is not subject to trademark rights and can be used by any manufacturer once patent protection expires.

- Construction: Generic names are built using a system of stems (prefixes, infixes, and suffixes) that categorize the drug into a pharmacological family. For instance, the suffix -statin immediately identifies a drug as an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor used to lower cholesterol (e.g., atorvastatin, simvastatin).

- The “Public Good” Aspect: The assignment of a generic name is a collaborative effort involving national bodies like the USAN Council and international bodies like the WHO INN Programme. This ensures that the name is usable in multiple languages and does not convey promotional claims. For example, names cannot imply efficacy (e.g., “cancer-cure”) or target specific organs (e.g., “liver-fix”) to avoid limiting the drug’s off-label or future indications.

- Regional Variations and Harmonization: Historically, different countries maintained their own generic naming systems. The UK had British Approved Names (BAN), and Japan had Japanese Accepted Names (JAN). However, significant efforts have been made to harmonize these with the WHO INN to prevent confusion. A classic example of this harmonization was the shift in the US from “albuterol” (USAN) to “salbutamol” (INN) in international contexts, or the transition of “adrenaline” to “epinephrine” in certain jurisdictions. The USAN Council now works in close concert with the WHO to ensure new names are identical globally.

- Salt Policy Changes: In 2013, the FDA and USP changed their policy regarding salt nomenclature. Previously, the generic name often included the salt form (e.g., pseudoephedrine hydrochloride). The new policy prefers naming the active moiety alone on the label of the finished dosage form to prevent medication errors where patients might confuse different salts of the same active ingredient, although the salt is still specified in the ingredient list.

2.3 The Brand Name: The Marketing Identity

The brand name, or proprietary name, is a trademark owned by the pharmaceutical company holding the patent. It is designed to be catchy, memorable, and evocative of the drug’s benefit, standing in stark contrast to the sterile scientific utility of the generic name.

- Psychology of Naming: Brand names often utilize “power letters” like X, Z, and Q (e.g., Xanax, Prozac, Zithromax) to appear high-tech and potent. They are linguistically engineered to be distinct and euphonious. The name Viagra, for example, suggests vigor and vitality.

- Regulatory Constraints: While companies have creative license, regulators like the FDA and EMA strictly vet brand names. The FDA’s Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (DMEPA) conducts simulation studies to ensure a proposed brand name does not look or sound like an existing product when handwritten or spoken. A name like “Amocillin” would be rejected for being too close to “Amoxicillin”. Furthermore, names cannot be “false or misleading.” A drug cannot be named “Bestplatin” as it implies superiority over other platinum-based chemotherapies.

- The Patent Cliff: When a drug’s patent expires, the brand name remains the property of the innovator, but the drug can be marketed by competitors under the generic name or new branded-generic names. This transition is a critical economic event in the pharmaceutical lifecycle, often leading to a proliferation of names for the same molecule.

Table 1: Comparative Anatomy of Drug Names

| Feature | Chemical Name | Generic Name (Nonproprietary) | Brand Name (Proprietary) |

| Origin | IUPAC Rules | USAN Council / WHO INN | Pharmaceutical Manufacturer |

| Purpose | Scientific description of molecular structure | Global identification & classification | Marketing & Brand Loyalty |

| Ownership | Public Domain | Public Domain | Private Trademark |

| Examples | N-acetyl-p-aminophenol | Acetaminophen / Paracetamol | Tylenol |

| 7-chloro-1,3-dihydro-1-methyl-5-phenyl… | Diazepam | Valium | |

| (RS)-2-(4-(2-methylpropyl)phenyl)propanoic acid | Ibuprofen | Motrin | |

| ethyl 4-(8-chloro-5,6-dihydro-11H-benzo… | Loratadine | Claritin |

3. Global Regulatory Frameworks and Harmonization

The governance of drug nomenclature is a diplomatic and scientific feat, requiring coordination across borders, languages, and legal systems. It is not enough for a name to be chemically accurate; it must be culturally neutral, phonetically distinct in dozens of languages, and legally available.

3.1 The WHO International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Programme

Established in 1950, the WHO INN Programme is the supreme authority on global drug nomenclature. Its mandate is to select a single name of worldwide acceptability for each active substance.

- Principles of Selection: The WHO mandates that INNs be distinctive in sound and spelling, not inconveniently long, and free from anatomical or physiological references that could limit future uses. For example, naming a drug “lung-cure” would be rejected as it implies a specific therapeutic outcome that might not be its only use, and it suggests efficacy that might not be universal.

- Protection of Stems: The WHO rigorously protects “stems” (common syllables used to denote pharmacological groups). Companies are prohibited from using these stems in their brand names to avoid confusing the generic classification system. For example, a brand name cannot end in “-olol” if it is not a beta-blocker. This protection helps maintain the integrity of the taxonomic system.

- Language Independence: INNs are designed to be easily pronounced and spelled across major languages (English, French, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Arabic). This requirement drives specific orthographic rules:

- “ph” is replaced by “f” (e.g., sulfur instead of sulphur).

- “th” is replaced by “t”.

- “ae” or “oe” is replaced by “e”.

- “y” is replaced by “i”.

- These rules ensure that amoxicillin looks and sounds roughly the same whether prescribed in Paris, Cairo, or Beijing.

3.2 The United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council

In the United States, the USAN Council is the designated body for assigning generic names. It is a tri-partite organization sponsored by the American Medical Association (AMA), the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA), with FDA liaison.

- The USAN Process: A pharmaceutical company typically applies for a USAN during the Investigational New Drug (IND) phase of development. The Council reviews the chemical structure and pharmacological action to assign the appropriate stem.

- Timing: The application usually occurs when the drug is in Phase I or Phase II clinical trials. Waiting too long can delay marketing approval, as the FDA requires a USAN for labeling.

- Cost and Administration: The process involves a fee and a negotiation period. The manufacturer proposes names, but the Council has the final say, often rejecting proposals that are too promotional or similar to existing names.

- Relationship with WHO: The USAN Council works closely with the WHO INN Expert Committee. In most cases, the USAN and INN are identical. However, historical divergences exist (e.g., acetaminophen in the US vs. paracetamol internationally; meperidine vs. pethidine). Current policies strive for 100% harmonization to support the global pharmaceutical supply chain. If a USAN differs from an INN, the USAN Council will often petition the WHO or vice-versa to align them, though entrenched names are rarely changed due to safety risks.

3.3 The Role of Pharmacopoeias

Once a name is established, it is enshrined in pharmacopoeias (such as the USP, BP, or EP). These compendia set the legal quality standards for the drug. The generic name becomes the legal title under which the drug’s purity, strength, and quality are measured. If a product is labeled with a USP name, it must meet USP standards.

4. The Taxonomy of Therapeutics: Decoding Drug Stems

The genius of the modern nomenclature system lies in the use of stems. These linguistic keys unlock the pharmacological identity of a drug, allowing healthcare professionals to deduce a drug’s class, mechanism of action, and potential side effects simply by reading its name. Stems essentially create a “Periodic Table” of drugs.

4.1 Common Stems and Their Meanings

Stems can appear as prefixes, infixes, or suffixes. The rigorous application of these stems prevents chaos in the pharmacy and aids in the rapid identification of new agents.

- -caine: Indicates local anesthetics (e.g., lidocaine, procaine). This stem warns of potential sodium channel blocking activity. Historically derived from cocaine, the first local anesthetic.

- -olol: A hallmark of beta-adrenergic blockers (e.g., propranolol, atenolol). A physician seeing this suffix immediately knows the drug is likely used for hypertension or arrhythmias and contra-indicated in asthma.

- -statin: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (e.g., lovastatin, rosuvastatin). This is perhaps one of the most recognized stems due to the prevalence of cholesterol management.

- -pril: ACE inhibitors (e.g., lisinopril, enalapril). This stem signals a mechanism involving the renin-angiotensin system and potential side effects like dry cough.

- -vir: Antiviral substances. This stem is often combined with substems to indicate the specific target:

- -navir: HIV protease inhibitors (e.g., ritonavir).

- -osivir: Influenza neuraminidase inhibitors (e.g., oseltamivir).

- -prazole: Proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole). Used for gastric acid suppression.

- -sartan: Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (e.g., losartan). An alternative to ACE inhibitors.

4.2 The Evolution of Monoclonal Antibody Nomenclature

No class of drugs illustrates the complexity of nomenclature better than monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). As these biological agents moved from mouse-derived to human-derived proteins, their names evolved to reflect their “humanity” and immunogenicity potential.

- The -mab Suffix: All monoclonal antibodies end in -mab.

- Source Sub-stems (Infixes): Until recently, the syllable preceding -mab indicated the source of the antibody, which was a proxy for the risk of allergic reaction:

- -o-: Mouse (murine) (e.g., muromonab – high immunogenicity risk).

- -xi-: Chimeric (mouse/human) (e.g., infliximab – moderate risk).

- -zu-: Humanized (e.g., trastuzumab – low risk).

- -u-: Fully human (e.g., adalimumab – lowest risk).

- Recent Changes (2017/2021): As technology advanced, the distinction between “humanized” and “fully human” became blurred and scientifically ambiguous. In 2017, the WHO revised the system to remove source substems for general use, anticipating that most new mAbs would be human or humanized. The focus shifted to the target infix (e.g., -li- for immunomodulators). This change simplifies names but removes the immediate “source” information that clinicians had grown used to.

Table 2: Key Drug Stems and Pharmacological Classes

| Stem | Position | Drug Class / Mechanism | Examples |

| -vir | Suffix | Antivirals | Acyclovir, Remdesivir |

| -mab | Suffix | Monoclonal Antibodies | Rituximab, Infliximab |

| -cillin | Suffix | Penicillins (Antibiotics) | Amoxicillin, Methicillin |

| -azole | Suffix | Antifungals (Azole derivatives) | Fluconazole, Ketoconazole |

| -sartan | Suffix | Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) | Losartan, Valsartan |

| -prazole | Suffix | Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) | Omeprazole, Pantoprazole |

| -tinib | Suffix | Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors | Imatinib, Gefitinib |

| gli- | Prefix | Sulfonylurea Hypoglycemics | Glipizide, Glyburide |

| -grel- | Infix/Suffix | Platelet aggregation inhibitors | Clopidogrel, Ticagrelor |

5. Biologics and Biosimilars: The Nomenclature of Complexity

The biotechnology revolution introduced large, complex molecules that defied the simple characterization of small-molecule drugs. This necessitated a new, controversial chapter in drug nomenclature: the naming of biosimilars. Unlike aspirin (a small molecule with a fixed structure), biologics are large proteins produced in living cells. Their exact structure can vary slightly depending on the manufacturing process (glycosylation patterns, folding). Therefore, a “generic” biologic (biosimilar) is highly similar but not identical to the reference product.

5.1 The FDA’s 4-Letter Suffix Rule

To ensure pharmacovigilance—the ability to trace an adverse event to a specific manufacturer’s product—the FDA implemented a unique naming convention for biosimilars that differs significantly from the standard generic system.

- The Rule: The nonproprietary name of a biological product must consist of a core name (e.g., infliximab) attached by a hyphen to a four-letter suffix that is devoid of meaning.

- The “Devoid of Meaning” Controversy: The FDA explicitly requires these suffixes to be random. They cannot spell words or abbreviations (e.g., -pfzr for Pfizer would be rejected).

- Rationale: This randomness is intended to prevent any implication that one biosimilar is superior to another based on its manufacturer’s reputation, while still ensuring unique identification. It levels the playing field but makes the names harder to remember.

- Examples:

- Reference Product: Infliximab (Remicade).

- Biosimilars: Infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra), Infliximab-abda (Renflexis), Infliximab-qbtx (Ixifi).

5.2 The Divergence: US vs. EU Approaches

A significant geopolitical rift exists in biosimilar naming, creating complexity for global manufacturers.

- United States: Adheres to the suffix rule (Core name + random suffix).

- European Union: Does not use suffixes. The EU relies on the combination of the INN and the Brand Name (or company name) to distinguish products. They argue that the suffix system is confusing and unnecessary if batch numbers and brand names are properly recorded in adverse event reporting.

- Implications: This divergence creates a headache for global supply chains. A vial of adalimumab manufactured in the same facility might need to be labeled adalimumab-atto for the US market and simply adalimumab (with a trade name) for the European market.

5.3 The WHO Biological Qualifier (BQ) Proposal

The WHO attempted to solve this global divergence with the “Biological Qualifier” (BQ) proposal—a four-letter alphabetic code assigned to all biological active substances. However, this system faced resistance and has not been universally adopted, leaving the world with a fragmented system: the US uses suffixes, the EU does not, and other regions mix approaches.

5.4 Interchangeability and Naming

The naming debate is closely tied to the concept of interchangeability. In the US, an “interchangeable” biosimilar is one that can be substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist without the intervention of the prescribing doctor (similar to standard generics). The naming convention (using distinct suffixes) reinforces the idea that these products are distinct entities until proven interchangeable—a regulatory hurdle that is higher in the US than in Europe, where interchangeability is increasingly assumed upon approval.

Table 3: Recent FDA-Approved Biosimilars and Their Suffixes (2024)

| Biosimilar Name | Core Name + Suffix | Reference Product | Approval Date |

| Pavblu | aflibercept-ayyh | Eylea | Aug 2024 |

| Enzeevu | aflibercept-abzv | Eylea | Aug 2024 |

| Epysqli | eculizumab-aagh | Soliris | July 2024 |

| Ahzantive | aflibercept-mrbb | Eylea | June 2024 |

| Nypozi | filgrastim-txid | Neupogen | June 2024 |

| Pyzchiva | ustekinumab-ttwe | Stelara | June 2024 |

| Yesafili | aflibercept-jbvf | Eylea | May 2024 |

6. Commercial Linguistics: The Art and Science of Brand Naming

While the generic name is a creature of science and regulation, the brand name is a creature of commerce. It is the only part of the nomenclature controlled by the manufacturer, and it is a multimillion-dollar asset.

6.1 The Branding Strategy

Pharmaceutical branding is a high-stakes game. A name must be distinctive, pronounceable, and carry positive connotations without making illegal claims.

- Phonosemantics: Marketers often use “plosive” consonants (P, T, K, B, D, G) to make names sound strong and effective, or “fricatives” (F, V, S, Z) to sound fast or soothing. The heavy use of X, Z, and Q (e.g., Xeljanz, Zyprexa, Qulipta) is a deliberate strategy to create a “sci-fi” or high-tech aura and to ensure the name is unique for trademark purposes.

- Subliminal Associations: Names are often derived from root words that suggest the drug’s benefit. Lasix (furosemide) implies “LAst SIx hours” (duration of action). Premarin comes from “PREgnant MARes’ urINe” (the source of the estrogen). Ambien suggests “Ambient” or “Good Morning” (AM + Bien).

6.2 Regulatory Review: The DMEPA Gauntlet

The FDA’s Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (DMEPA) holds veto power over brand names. Their primary concern is safety, not marketing.

- Simulation Studies: DMEPA conducts studies where they ask healthcare professionals to write out and interpret the proposed name. If a significant percentage confuses the new name with an existing one, it is rejected.

- Rejection Rates: It is estimated that up to 40% of proposed brand names are rejected. Companies often submit 2-3 backup names during the NDA process to ensure one survives scrutiny.

- Misleading Claims: A name cannot overstate efficacy. Rogaine (for hair loss) was originally going to be named Regain, but the FDA rejected it because it implied a guaranteed full restoration of hair, which the drug could not promise.

7. Pharmacovigilance and Safety: Naming as a Defense Against Error

Drug nomenclature is a critical component of patient safety. Confusing drug names are a leading cause of medication errors, resulting in patient harm and death. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) and the FDA have developed specific strategies to mitigate these risks through nomenclature modifications.

7.1 Look-Alike Sound-Alike (LASA) Errors

The sheer volume of drug names (over 20,000 approved products) makes phonetic or orthographic overlap inevitable.

- The Problem: Pairs like Celexa (antidepressant) and Celebrex (anti-inflammatory), or Vinblastine and Vincristine (both chemotherapy agents but with vastly different dosing regimens), are notorious for causing dispensing errors.

- Consequences: A pharmacist misreading a handwritten prescription or a nurse selecting the wrong vial from an automated cabinet can lead to fatal outcomes. For example, confusing acetoHEXAMIDE (for diabetes) with acetaZOLAMIDE (for glaucoma/altitude sickness) could cause severe hypoglycemia in a patient who needs neither.

7.2 Tall Man Lettering

To combat LASA errors, the FDA and ISMP introduced “Tall Man” lettering. This convention uses mixed-case letters to highlight the distinguishing sections of similar drug names.

- Mechanism: By capitalizing the unique parts of the name, the visual distinctiveness is enhanced, forcing the clinician’s brain to pause and process the difference. Eye-tracking studies have confirmed that this alteration draws attention to the differentiating syllables.

- Implementation:

- predniSONE vs. prednisoLONE

- hydrOXYzine vs. hydrALAZINE

- DOBUTamine vs. DOPamine

- vinCRIStine vs. vinBLAStine.

- Adoption: This system is now standard in electronic health records (EHRs), pharmacy dispensing software, and on physical drug labels.

7.3 The “Drug Facts” Label

For Over-the-Counter (OTC) medications, the “Drug Facts” label is the primary tool for communicating nomenclature to the lay public.

- Standardization: Mandated by the FDA, this label clearly lists the “Active Ingredient” (Generic Name) at the top, separate from the “Uses” and “Warnings.”

- Consumer Safety: This transparency is crucial for preventing double-dosing. A patient taking “Tylenol” for pain and “NyQuil” for a cold might not realize both contain acetaminophen without checking the Drug Facts label. Overdose of acetaminophen is a leading cause of acute liver failure, making this nomenclature clarity a life-or-death issue.

Visual Suggestion: A “Before and After” comparison of a drug label. The “Before” shows standard lowercase text where names look identical (chlorpropamide vs chlorpromazine). The “After” demonstrates Tall Man lettering (chlorproPAMIDE vs chlorproMAZINE) and clear blocking of the Drug Facts panel.

8. The Drug Development Lifecycle: A Naming Timeline

The journey of a drug name parallels the journey of the molecule itself, from a lab code to a household brand. This process can take years and involves multiple stakeholders.

8.1 Phase 1: The Code Name (Pre-Clinical)

In the early discovery phase, a compound is known only by an alphanumeric code assigned by the company.

- Examples: UK-92,480 became Sildenafil (Viagra); RU-486 became Mifepristone.

- Purpose: These codes allow internal tracking and intellectual property protection before a patent is fully public. They are often used in early scientific publications.

8.2 Phase 2: The Generic Name Application (Phase I/II)

As the drug enters clinical trials (Investigational New Drug status), the company applies to the USAN Council.

- Negotiation: The company proposes a name based on the chemical structure and appropriate stem. The Council reviews it for conflict with existing names and scientific accuracy. This process can take several months.

- International Clearance: Once the USAN is approved, it is submitted to the WHO INN Programme to ensure global alignment. This is the moment the drug officially joins the global pharmacopoeia.

8.3 Phase 3: The Brand Name Strategy (Phase III/NDA)

While clinical trials progress to Phase III, marketing teams brainstorm brand names.

- Safety Review: As part of the New Drug Application (NDA), the proposed brand name is submitted to the FDA. The DMEPA performs its safety review.

- Final Approval: The brand name is officially approved only when the NDA is approved for marketing. Until that moment, the name is tentative and can be pulled if safety concerns arise.

9. Digital Dimensions: Drug Nomenclature in the SEO Era

In the digital age, drug nomenclature has taken on a new dimension: Search Engine Optimization (SEO). Patients and healthcare providers increasingly rely on search engines to find drug information, creating a distinct digital ecosystem for drug names.

9.1 Search Behavior: Generic vs. Brand

- Patient Intent: Patients typically search for symptoms (“flu shot near me,” “pain relief”) or Brand Names they see in advertisements (Ozempic, Viagra). High volume keywords include “24-hour pharmacy” and “generic drugs”.

- Professional Intent: Healthcare professionals and researchers are more likely to search for Generic Names or specific mechanisms of action (semaglutide, sildenafil citrate).

- The Cost Factor: The high search volume for “generic drugs” (135,000+ monthly searches) indicates that cost is a primary driver for users, who are often looking for the cheaper generic equivalent of a brand they were prescribed.

9.2 Pharmaceutical SEO Strategies

- YMYL (Your Money Your Life): Google classifies pharmaceutical content as YMYL, requiring the highest standards of Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness (E-E-A-T). Websites must use correct nomenclature to signal authority.

- The Biosimilar SEO Challenge: With the complex suffixes of biosimilars (e.g., infliximab-dyyb), manufacturers face a unique challenge. Users are unlikely to type the random suffix. Therefore, SEO strategies must focus on the core generic name (infliximab) while educating users about the specific branded biosimilar (Inflectra) to capture traffic.

10. Future Horizons: Gene Therapies and Advanced Medicinal Products

As science advances, nomenclature must adapt. The current systems, designed for small molecules and simple proteins, are being stretched by the arrival of gene therapies, cell therapies, and personalized vaccines.

10.1 Gene and Cell Therapy Naming

The USAN Council and WHO are currently developing frameworks for naming cellular therapies.

- Stems for Cells: Suffixes like -gen (gene therapy vectors) or -cel (cellular therapies) are emerging. For example, tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) uses the -leucel suffix to denote autologous T-cells modified with a lentiviral vector.

- Complexity: These names are often incredibly long and difficult to pronounce (e.g., talimogene laherparepvec), leading to calls for a simplified naming convention that retains scientific meaning without being tongue-twisters.

10.2 AI and Automated Naming

With the explosion of drug candidates discovered by Artificial Intelligence (AI), the volume of names required will skyrocket. We may see the integration of AI into the naming process itself—algorithms that generate USAN/INN candidates that automatically check for phonetic conflicts and trademark availability in real-time, streamlining the years-long process into weeks.

11. Conclusion

Drug nomenclature is a discipline of profound responsibility. It is the invisible thread that connects the molecular geometry of a compound to the bedside of a patient. From the rigid IUPAC chemical descriptions to the carefully negotiated stems of the INN system, and finally to the evocative marketing of brand names, every syllable serves a purpose.

The evolution of this field reflects the evolution of medicine itself. We have moved from simple salts to complex biologics, and our language has evolved from “Iron Tonic” to “Infliximab-dyyb.” As we enter the era of gene editing and personalized medicine, the challenges of naming will only grow. The controversies over biosimilar suffixes and the constant battle against LASA errors highlight that nomenclature is not static; it is a dynamic safety system that must be continuously maintained.

For the researcher, the regulator, and the clinician, understanding the rules of this lexicon is not optional—it is a prerequisite for safe and effective practice. In the high-stakes world of pharmacology, a name is never just a name; it is a code for safety, identity, and hope.

References & Bibliography

The following reputed texts and sources were utilized in the compilation of this report:

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 14th Edition. Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, editors. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 15th Edition. Katzung BG, Vanderah TW, editors. McGraw Hill; 2021.

- Rang and Dale’s Pharmacology, 9th Edition. Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G, Loke YK, MacEwan D, Rang HP. Elsevier; 2020.

- WHO INN Programme Guidelines. World Health Organization. “General principles for guidance in devising International Nonproprietary Names for pharmaceutical substances.”

- USAN Council Guidelines. American Medical Association. “United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council naming guidelines and stems.”

- FDA Guidance for Industry. “Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ISMP Medication Safety Alerts. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. “List of Confused Drug Names” and “Tall Man Letters.”

- IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry.

📚 AI Pharma Quiz Generator

🎉 Quiz Results

Medical Disclaimer

The medical information on this post is for general educational purposes only and is provided by Pharmacology Mentor. While we strive to keep content current and accurate, Pharmacology Mentor makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the post, the website, or any information, products, services, or related graphics for any purpose. This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment; always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition and never disregard or delay seeking professional advice because of something you have read here. Reliance on any information provided is solely at your own risk.