Introduction

Nausea and vomiting are defensive reflexes that protect the body from ingested toxins and noxious substances, but they can also emerge from various benign or pathological stimuli. From motion sickness and morning sickness to chemotherapy-induced and postoperative nausea and vomiting, these symptoms can significantly impact quality of life. Consequently, the search for effective antiemetic drugs has long been a priority in pharmacology and clinical medicine.

This extensive overview delves into the pharmacology of antiemetic medications, addressing the physiology of the vomiting reflex, classification of antiemetic agents, mechanisms of action, clinical applications, side effects, and ongoing developments in the field. We integrate examples of key antiemetic drug classes—such as 5-HT₃ receptor antagonists, D₂ receptor antagonists, NK₁ receptor antagonists, and more—and explore how their therapeutic benefits must be weighed against potential adverse effects. References and insights are derived from “Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics” (13th Edition), “Katzung BG, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology” (15th Edition), and “Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology” (8th Edition).

Physiology of Nausea and Vomiting

The Vomiting Center

A central “vomiting center” located in the medulla oblongata orchestrates the complex act of vomiting. This center receives and integrates signals from multiple sources:

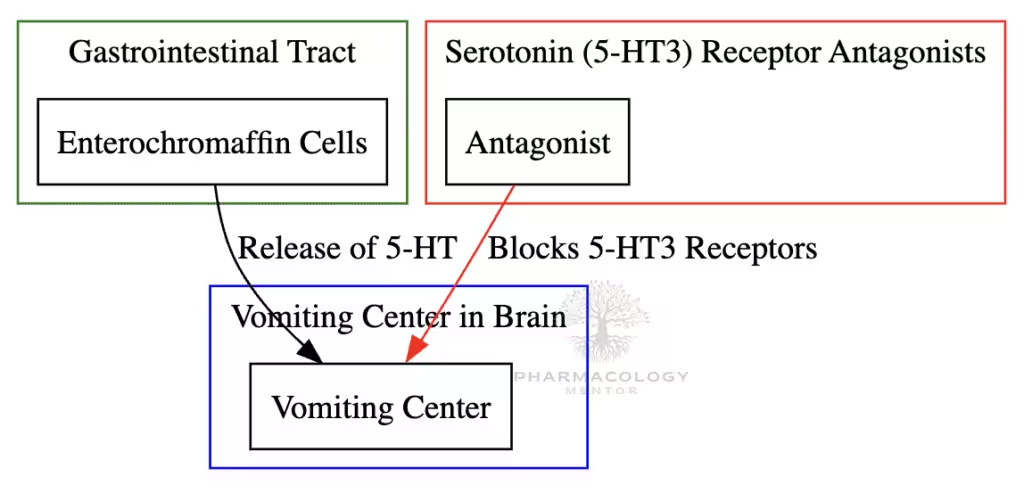

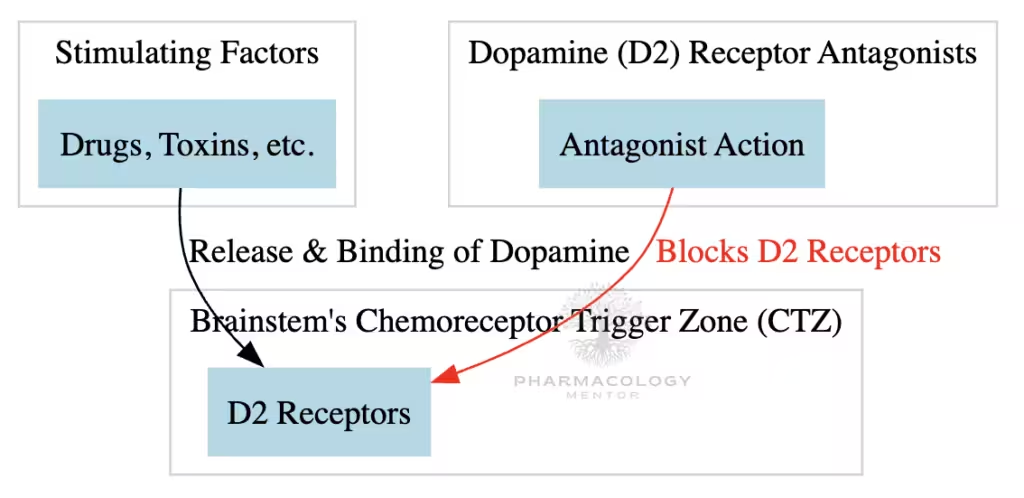

- Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone (CTZ): Situated in the area postrema, it lies outside the blood–brain barrier and is stimulated by blood-borne drugs or toxins. The CTZ is packed with dopamine D₂, 5-HT₃, and neurokinin-1 (NK₁) receptors, among others.

- Vestibular System: Communicates via cranial nerve VIII. Histamine (H₁) and acetylcholine (muscarinic) receptors here can trigger vomiting associated with motion sickness.

- Visceral Afferents: Mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors in the GI tract send signals via the vagus and sympathetic nerves to the nucleus tractus solitarius, which relays impulses to the vomiting center. Irritation of the GI lining or distension commonly initiates this pathway.

- Higher Brain Centers: Emotional stimuli, pain, or disagreeable sights and smells can activate cortical and limbic circuits that influence vomiting.

When sufficiently stimulated, the vomiting center coordinates the somatic and autonomic outflow the leads to the emetic response—forceful contraction of abdominal muscles, retrograde propulsion, and expulsion of gastric contents.

Mediators and Key Receptors

Multiple neurotransmitters and receptors mediate the sensation of nausea and the act of vomiting:

- Dopamine (D₂) Receptors: Abundant in the CTZ.

- Serotonin (5-HT₃) Receptors: Common in the vagal afferents and CTZ.

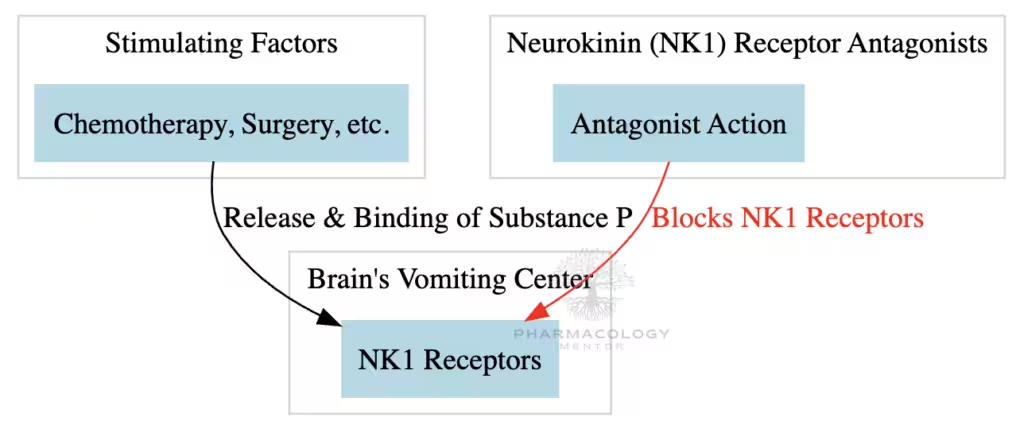

- Neurokinin-1 (NK₁) Receptors: Activated by substance P in both the CTZ and vomiting center.

- Muscarinic (M1) and Histamine (H1) Receptors: Predominantly in the vestibular system and vomiting center.

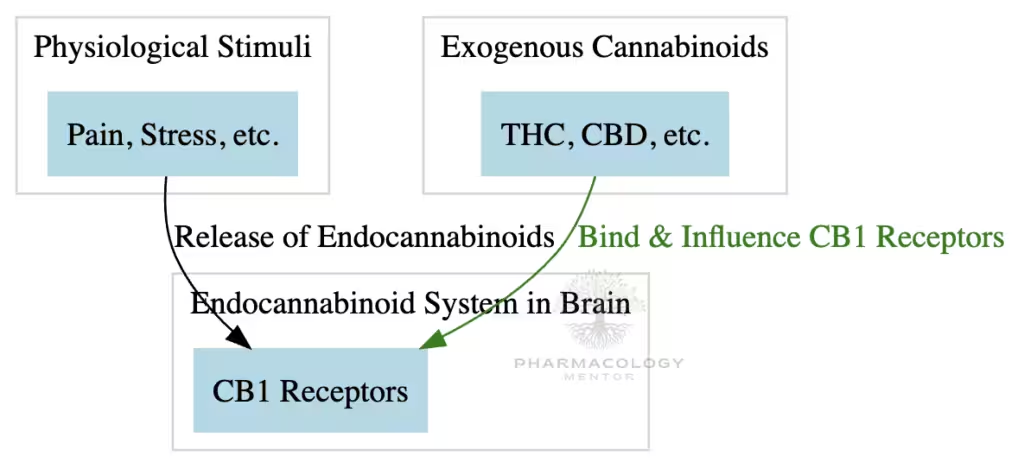

- Cannabinoid (CB1) Receptors: In the central nervous system, relevant for certain antiemetic interventions.

Therapeutic strategies frequently target these receptor systems to mitigate or preempt vomiting.

Classification of Antiemetic Drugs

Broadly, antiemetics may be categorized by their primary receptor targets or clinical indications. Common classes include:

- 5-HT₃ Receptor Antagonists: Ondansetron, Granisetron, Palonosetron

- D₂ Receptor Antagonists: Metoclopramide, Prochlorperazine, Haloperidol

- NK₁ Receptor Antagonists: Aprepitant, Fosaprepitant

- Antihistamines (H1) and Anticholinergics (M1): Dimenhydrinate, Meclizine, Scopolamine

- Benzodiazepines: Lorazepam, Diazepam (adjunct therapy)

- Glucocorticoids: Dexamethasone, Methylprednisolone (often combined in chemotherapy regimens)

- Cannabinoids: Dronabinol, Nabilone

- Others: Ginger Extract, certain antidepressants, or GABA modulators (under study)

Clinicians commonly select one or more agents based on the etiology of the nausea—chemotherapy-induced, postoperative, radiation-induced, or motion sickness, among others.

5-HT₃ Receptor Antagonists

Mechanism of Action

Serotonin (5-HT) released by enterochromaffin cells in the gut during chemotherapy or irritation activates 5-HT₃ receptors on vagal afferents, sending intense signals to the vomiting center. 5-HT₃ receptor antagonists impede this reflex arc both peripherally (on vagal terminals) and centrally (in the CTZ).

Key Agents

- Ondansetron: The prototype. Highly effective in chemotherapy-induced nausea and postoperative cases.

- Granisetron: Similar to ondansetron but with a longer half-life.

- Dolasetron: Similar efficacy; caution with potential QT prolongation.

- Palonosetron: Notable for a prolonged half-life (~40 hours), making it ideal for preventing delayed chemotherapy-induced vomiting.

Clinical Uses

Primarily indicated for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) (acute phase), radiation-induced nausea, and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Some also use them off-label for severe gastroenteritis or other refractory vomiting.

Adverse Effects

- Headache, constipation, dizziness are common.

- QT Interval Prolongation: The class (especially older generation) can prolong the QT interval. Caution is required in patients with cardiac risk.

- Generally safe with few drug interactions (metabolized via CYP450).

Neurokinin-1 (NK₁) Receptor Antagonists

Mechanism of Action

Substance P, an important neuropeptide in the vomiting pathway, binds to NK₁ receptors in both peripheral afferents and centrally in the area postrema. NK₁ receptor antagonists (e.g., Aprepitant) block these receptors, significantly preventing both acute and delayed phases of chemotherapy-induced vomiting.

Key Agents

- Aprepitant (oral) and Fosaprepitant (IV): Often combined with 5-HT₃ antagonists and dexamethasone to manage highly emetogenic chemotherapy protocols (e.g., cisplatin).

- Rolapitant, Netupitant: Also NK₁ inhibitors, with varying half-lives and usage indications.

Clinical Uses

Most effective in delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea (beyond the first 24 hours post-chemotherapy). Used frequently in combination with other antiemetic classes for synergistic protection.

Adverse Effects

- Hiccups and fatigue are relatively common.

- Drug Interactions: Metabolized by CYP3A4, so caution with co-administered drugs (e.g., certain chemotherapeutics, warfarin).

Dopamine (D₂) Receptor Antagonists

Mechanism of Action

D₂ receptors in the CTZ can be stimulated by toxins, leading to activation of the vomiting reflex. By blocking D₂, these agents reduce emetic signaling to the vomiting center.

Subclasses

- Phenothiazines: Prochlorperazine, Chlorpromazine

- Butyrophenones: Haloperidol, Droperidol

- Benzamides: Metoclopramide, Domperidone

Phenothiazines

- Broad receptor blockade: D₂, muscarinic, histamine.

- Prochlorperazine is commonly used for general nausea and mild to moderate CINV.

- Adverse effects: Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

Butyrophenones

- Haloperidol, Droperidol: Primarily block D₂ in the CTZ, though also some alpha-blocking properties.

- Indicated for acute or refractory nausea in various contexts.

- Adverse effects: QT prolongation (especially droperidol), EPS, sedation.

Benzamides

- Metoclopramide: Central D₂ blockade plus peripheral prokinetic effect (enhancing GI motility via 5-HT₄ agonism). Useful in gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying.

- Domperidone: Similar to metoclopramide but primarily acts outside the BBB; less EPS risk, not widely available in some countries.

- Adverse effects: EPS (particularly metoclopramide), diarrhea, restlessness.

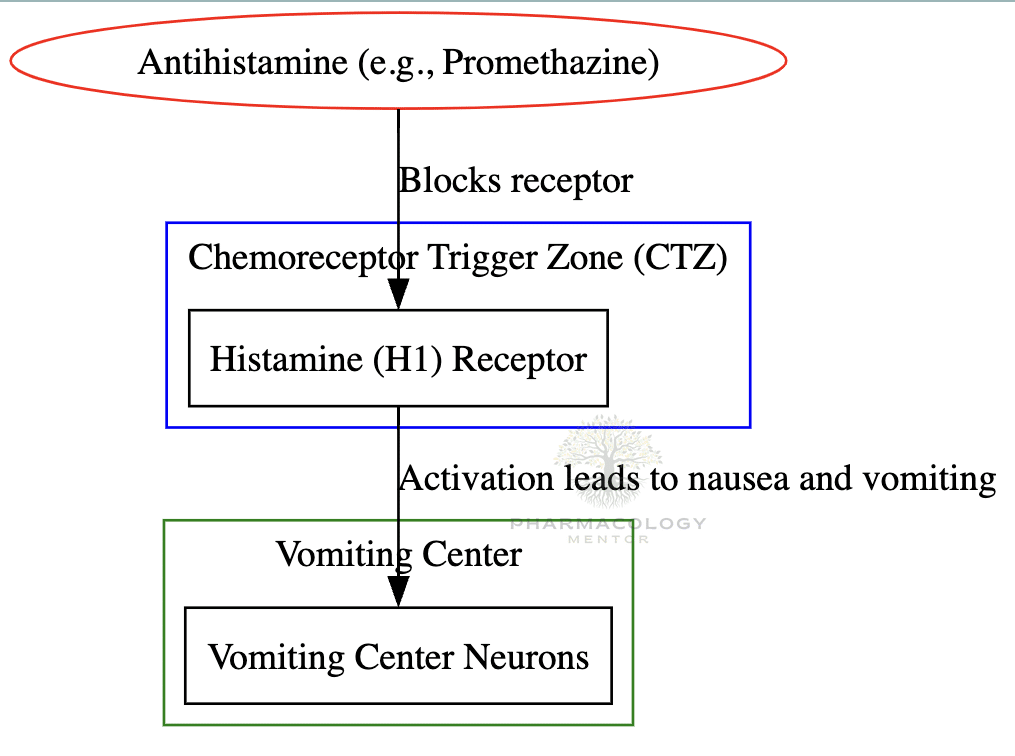

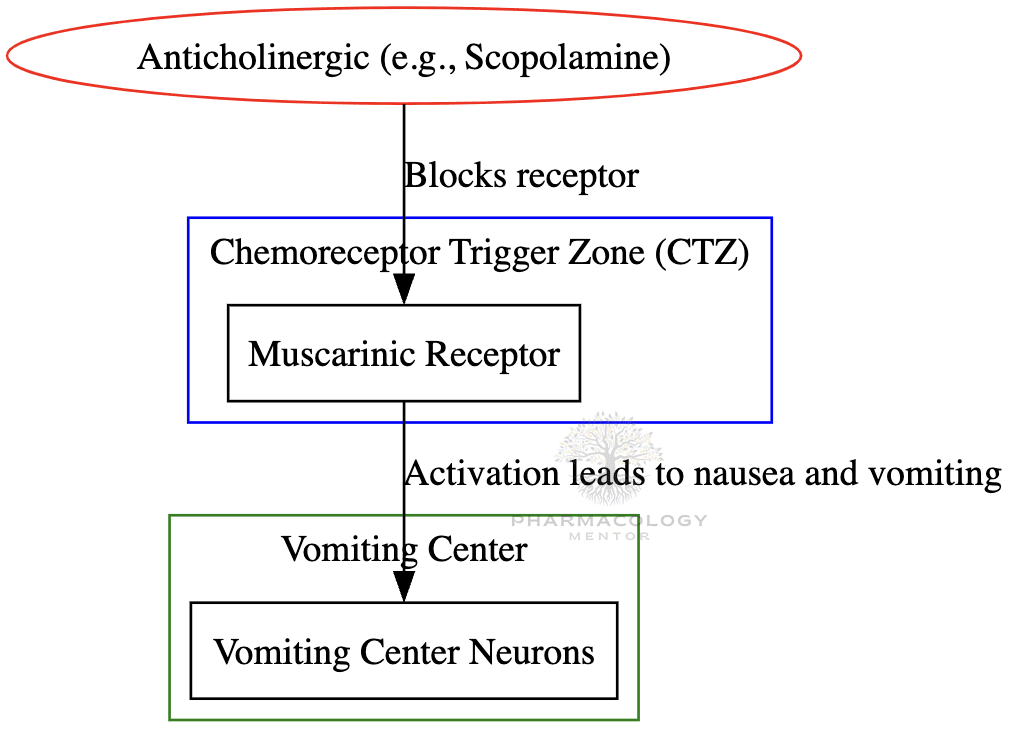

Histamine (H1) Antagonists and Anticholinergics (M1)

Mechanism of Action

These agents reduce stimulation from the vestibular apparatus and certain visceral afferents. They block H1 or muscarinic receptors that lead to signals converging on the vomiting center, especially in motion sickness.

Common Agents

- Dimenhydrinate: An H1 antihistamine; used prophylactically for motion sickness.

- Meclizine: Also an antihistamine with milder sedation; indicated for vertigo and motion sickness.

- Promethazine: A phenothiazine derivative that also blocks D2; widely used for various nausea situations but can sedate.

- Scopolamine (Hyoscine): A muscarinic antagonist; often used as a transdermal patch for motion sickness prophylaxis.

Indications

- Motion sickness: The main domain of antihistaminic/anticholinergic antiemetics.

- Vertigo or Meniere’s disease: Symptomatic relief via H1 blockade in the vestibular system.

- Postoperative or general nausea: Adjunct therapy.

Adverse Effects

- Sedation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, confusion (especially in the elderly).

- Scopolamine patches can cause memory issues or delirium in susceptible individuals.

Benzodiazepines

Mechanism of Action

Although not direct antiemetics, benzodiazepines (e.g., Lorazepam, Alprazolam, Diazepam) can reduce anxiety and anticipatory nausea and vomiting, particularly in chemotherapy settings. They potentiate GABA-A receptor activity, diminishing the stress and fear that can trigger vomiting.

Uses

- Adjunctive in highly emetogenic chemotherapy.

- Anticipatory nausea prophylaxis, reducing CNS anxiety loops.

- Preoperative sedation with mild antiemetic benefit.

Adverse Effects

- Sedation, drowsiness, dependence risk, respiratory depression if combined with other CNS depressants.

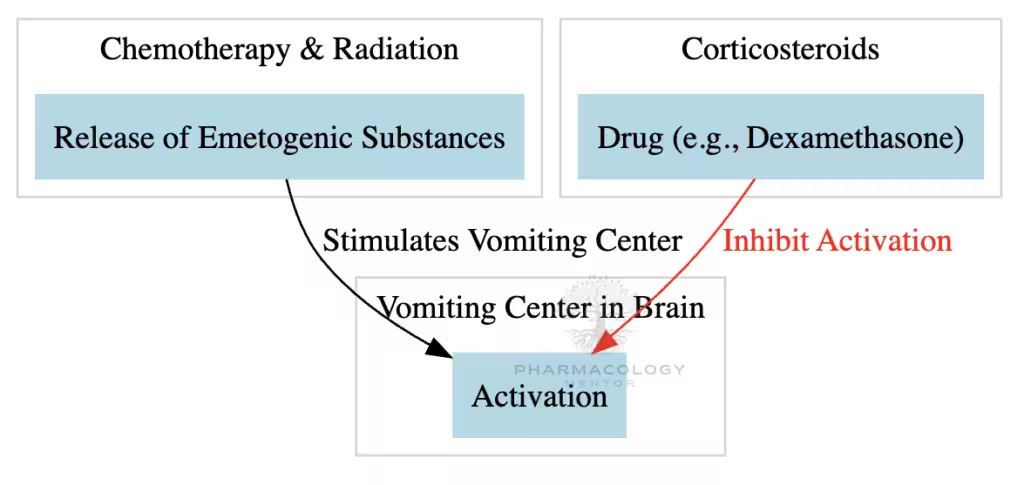

Glucocorticoids

Mechanism of Action

Dexamethasone and Methylprednisolone are frequently used for chemotherapy-induced or postoperative nausea in combination regimens. While the exact mechanism isn’t fully clarified, proposed actions include decreasing peritumoral inflammatory mediators (like prostaglandins) and stabilizing neuronal membranes.

Clinical Use

- Often co-administered with 5-HT₃ antagonists and NK₁ antagonists for highly emetogenic chemotherapy (e.g., cisplatin-based).

- Postoperative nausea prophylaxis (e.g., dexamethasone given pre-induction).

- Comparable or superior to some standard antiemetics when used in combination.

Adverse Effects

- Short-term: Hyperglycemia, mood changes, insomnia.

- Long-term or repeated courses: Risk of Cushingoid features, immunosuppression, bone demineralization.

Cannabinoids

Mechanism of Action

Cannabinoid receptors (CB1) in the central nervous system modulate the emetic reflex. Dronabinol (THC derivative) and Nabilone reduce nausea by activating these pathways, especially relevant in chemotherapy-induced scenarios when standard therapies fail.

Clinical Applications

- Refractory CINV that doesn’t respond to 5-HT₃ antagonists or NK₁ antagonists.

- Some use in AIDS-related anorexia to stimulate appetite.

Adverse Effects

- Euphoria, dysphoria, sedation, dizziness.

- Risk of psychotomimetic effects (hallucinations, paranoia).

- Potential for abuse and dependence.

Other Agents & Emerging Therapies

Olanzapine

An atypical antipsychotic with broad receptor binding (D₂, 5-HT₂, 5-HT₃, and more). Increasing evidence supports olanzapine as an efficacious antiemetic for highly emetogenic chemotherapy, often combined with NK₁ and 5-HT₃ antagonists plus dexamethasone.

Ginger Extract

Historically used as a natural antiemetic for mild nausea (e.g., motion sickness, mild GI upset). While some find relief, data regarding its efficacy in severe vomiting are limited.

Gabapentin or Pregabalin

Preliminary studies suggest that gabapentinoids can reduce postoperative nausea, possibly by lowering afferent neural excitability. Not yet mainstream for routine antiemetic prophylaxis, but a potential research avenue.

Novel Receptor Targets

Ongoing research aims to refine multi-receptor modulators or find new targets (like alpha-3beta-4 nicotinic receptors) to address refractory vomiting conditions. The challenge remains balancing increased efficacy with tolerable side effect profiles.

Clinical Indications and Combinations

Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV)

Profound synergy exists among 5-HT₃ antagonists, NK₁ antagonists, and dexamethasone—these three classes form the backbone of prophylaxis for moderately to highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Additional benzodiazepines or olanzapine might be added for difficult cases.

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV)

5-HT₃ antagonists (ondansetron, granisetron) and dexamethasone are go-to prophylactics. Scopolamine patches or droperidol can be considered, with caution for sedation and QT prolongation. Multimodal prophylaxis is recommended for high-risk patients (e.g., female, history of motion sickness, use of opioids).

Radiation-Induced Nausea

5-HT₃ antagonists (especially granisetron) plus/minus steroids. The severity depends on the anatomic site radiated and total dose.

Motion Sickness and Vestibular-Related Vomiting

Antihistamines (meclizine, dimenhydrinate) and anticholinergics (scopolamine patches) remain first-line. They must be administered prophylactically—once motion sickness is advanced, reversing it is harder.

Pregnancy-Related Nausea and Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Common first steps include vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) with or without doxylamine, an H1 antagonist. If severe, ondansetron or metoclopramide may be added. Avoiding potentially fetotoxic agents is critical.

Gastroenteritis

Mild to moderate acute gastroenteritis might be managed conservatively with rehydration. Ondansetron or dimenhydrinate may be used in children with persistent vomiting to prevent dehydration. Antibiotics or antimotility agents are usually restricted to specific causes.

Adverse Effects and Safety Considerations

Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS)

D₂ antagonists like metoclopramide or prochlorperazine can provoke dystonia, parkinsonism, or akathisia. Concomitant use of anticholinergics (e.g., benztropine) or dose adjustments can mitigate these reactions.

QT Prolongation

Some antiemetic classes, especially butyrophenones (droperidol) and older generation 5-HT₃ antagonists (especially IV dolasetron), can prolong the QT interval, risking torsades de pointes. Monitoring ECG and electrolytes is vital in high-risk patients.

Sedation and Anticholinergic Burden

Agents like promethazine, dimenhydrinate, scopolamine, or combination regimens can lead to sedation, confusion, blurred vision, urinary retention—particularly in older adults. Minimizing polypharmacy is advisable.

Serotonin Syndrome

Although rare, combining multiple serotonergic drugs (e.g., SSRIs, 5-HT₃ antagonists, tramadol) can precipitate serotonin syndrome. Awareness and vigilance are necessary if using broad polypharmacy.

Dependency and Abuse Potential

Benzodiazepines and cannabinoids carry risks of abuse or dependence. Strict adherence to guidelines and personalized evaluation helps limit these hazards.

Drug Interactions

- CYP450 Metabolism:

- Aprepitant (NK₁ antagonist) can inhibit or induce CYP3A4, affecting levels of warfarin, chemo agents, oral contraceptives.

- Ondansetron is metabolized by CYP3A4, but clinically significant interactions are generally less frequent.

- Additive Sedation:

- Combining benzodiazepines, antihistamines, or opioids can exacerbate CNS depression.

- QT Prolongation:

- Stacking known QT-prolonging drugs (e.g., droperidol + certain antibiotics, antifungals) elevates the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias.

- Dexamethasone with NK₁ Antagonists**:

- Aprepitant can increase dexamethasone plasma levels; often the steroid dose is halved to compensate.

Special Populations

Pediatric

- Ondansetron is often used for acute gastroenteritis with persistent vomiting.

- Avoid excessive sedation or EPS from D₂ antagonists. Dosage must be weight-based and carefully titrated.

Geriatric

- Higher susceptibility to anticholinergic adverse effects (e.g., confusion, delirium), sedation, orthostatic hypotension.

- QT prolongation risk is magnified with age-related cardiac changes and comorbidities.

Pregnancy

- Pyridoxine + doxylamine is standard for mild NVP.

- Ondansetron can be used if severity escalates, but potential concerns about fetal risk remain; data are mixed.

- Metoclopramide also an option but watch for EPS.

- Avoid known teratogens or inadequate safety data.

Pharmacogenomic Considerations

Some individuals may exhibit altered drug metabolism or heightened receptor sensitivities. Implementation of pharmacogenetic testing is still in preliminary stages but may refine antiemetic selection in the future.

Clinical Pearls and Implementation

- Identify the Cause: Tailor antiemetic choice to the underlying etiology—chemotherapy, motion sickness, pregnancy, or infection—to achieve optimal efficacy.

- Combination Therapy: Especially in CINV, synergy among 5-HT₃ antagonists, NK₁ antagonists, and dexamethasone is more effective than monotherapy.

- Prophylaxis vs. Rescue: For motion sickness, prophylactic dosing is key. For chemotherapy or postoperative settings, combining prophylaxis with rescue PRN (as-needed) options ensures coverage.

- Assess Cardiac Risk: Evaluate QT interval, baseline arrhythmias, or electrolyte imbalances before prescribing known QT-prolonging antiemetics.

- Evaluate Sedation: Sedative or anticholinergic loads can lead to falls, delirium (particularly in older patients). Opt for lower sedation profiles if feasible.

- Monitor for Extrapyramidal Reactions: If using D₂ antagonists in younger individuals (especially pediatric or female patients), ensure prompt recognition of dystonia or akathisia.

- Consider Oral, IV, Transdermal Routes: In severe vomiting, choosing a parenteral or transdermal route bypasses the GI tract, enhancing reliability.

Future Directions and Research

Personalizing Antiemetic Therapy

Precision medicine approaches—integrating genetic polymorphisms (e.g., CYP2D6, CYP3A4) and biomarker detection—could foreseeably optimize antiemetic selection and dosing. The goals: maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity.

Novel Targets

Research continues on novel peptides or ligand-gated ion channels within the gut-brain axis (e.g., G-protein-coupled receptors) that could yield more selective antiemetics without sedation or EPS.

Extended Use Cases

Antiemetics that also address pain, anxiety, or appetite might have broader utility in palliative care or complex medical conditions. Multifunctional agents such as olanzapine show potential in bridging antiemetic and anxiolytic or appetite-stimulating roles.

Impact on Quality of Life

Beyond controlling vomiting, effective antiemesis can improve nutritional status, patient adherence to chemo or radiation, postoperative recovery, and overall patient well-being. Ongoing psychosocial research underscores the importance of addressing the “burden” of nausea and the subjective experience of the patient.

Conclusion

Antiemetic drugs are an integral component of modern medical practice, encompassing a variety of pharmacologic classes that interrupt emetic pathways at multiple levels—gut, vestibular apparatus, chemoreceptor trigger zone, or higher CNS centers. Selecting the most suitable agent (or combination) hinges on accurately identifying the underlying cause (chemotherapy, motion sickness, postoperative setting, pregnancy, etc.) and balancing efficacy with the potential for side effects like extrapyramidal symptoms, QT prolongation, sedation, or anticholinergic effects.

Therapeutic advances—from 5-HT₃ antagonists to NK₁ receptor blockers, further improved by synergy with glucocorticoids or benzodiazepines—have redefined the management of previously intractable conditions, such as severe chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Despite these gains, continuing refinements are needed to ensure safer, more potent, and targeted antiemetic therapies, especially in vulnerable groups like infants, pregnant women, older adults, and those with comorbidities.

By combining a thorough knowledge of pharmacodynamics, patient-specific factors, and potential drug interactions, healthcare providers can maximize the quality of life for individuals suffering from nausea and vomiting. Ongoing research and emerging technologies promise further leaps in personalized antiemetic regimens that deliver precise, enduring relief from this widespread and debilitating symptom.

Citations

- Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13th Edition.

- Katzung BG, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 15th Edition.

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology, 8th Edition.

Medical Disclaimer

The medical information on this post is for general educational purposes only and is provided by Pharmacology Mentor. While we strive to keep content current and accurate, Pharmacology Mentor makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the post, the website, or any information, products, services, or related graphics for any purpose. This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment; always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition and never disregard or delay seeking professional advice because of something you have read here. Reliance on any information provided is solely at your own risk.