Introduction

Regulatory Pharmacology is the interdisciplinary field responsible for ensuring the safety, efficacy, and quality of medicines throughout their entire lifecycle. It stands at the critical intersection of pharmacology, toxicology, and regulatory law, providing the scientific foundation upon which government agencies approve new drugs and monitor their performance in the market. The purpose of this overview is to provide a detailed examination of the principles, processes, and governing bodies that shape modern drug regulation. This chapter will explore the foundational principles of the discipline, detail the mandatory pre-approval safety testing known as the “core battery,” compare the pathways to market approval in the U.S. and E.U., describe the crucial role of post-marketing surveillance, and discuss the future trends that are transforming the field.

1. The Foundations and Guiding Principles of Regulatory Pharmacology

This section establishes the core concepts and historical context of the field.

1.1. Defining the Discipline

Pharmacological studies are categorized based on their specific objectives. According to guidelines from the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH), these studies can be distinguished as follows:

- Primary Pharmacodynamics: These are studies concerning the mode of action and/or effects of a substance in relation to its desired therapeutic target (1, 2).

- Secondary Pharmacodynamics: These studies investigate the mode of action and/or effects of a substance not related to its desired therapeutic target (1, 2).

- Safety Pharmacology: This discipline investigates the potential undesirable pharmacodynamic effects of a substance on physiological functions, particularly within the therapeutic range and above. It is distinct from toxicology, which typically assesses adverse effects at high, chronic doses over extended periods (1, 3). Safety pharmacology’s unique mandate includes predicting the risk of rare but potentially lethal events (3).

1.2. The Historical Imperative: The Case of Terfenadine

The evolution of modern safety pharmacology was significantly influenced by the case of the antihistamine terfenadine (Seldane). In the mid-1990s, it was discovered that terfenadine, a non-cardiovascular drug, could cause Torsades de Pointes (TdP)—a rare but potentially lethal cardiac arrhythmia. Conventional preclinical toxicology testing at the time had failed to predict this risk. This failure highlighted a critical gap in drug safety assessment, as toxicology was designed to find overt organ damage at high, chronic doses, whereas the terfenadine problem was a rare pharmacodynamic effect at therapeutic doses—precisely the gap that Safety Pharmacology was created to fill. The terfenadine episode drove the development of safety pharmacology as a distinct field dedicated to bridging the gap between preclinical toxicology and clinical drug development (3).

1.3. The Key Regulatory Bodies: FDA and EMA

Two of the most influential regulatory agencies in the world are the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is a national agency of the United States. It has direct authority to approve drugs and regulates a wide range of products, including medicines, medical devices, and foods (4, 5). Its key centers, such as the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), are responsible for evaluating new drugs before they can be sold (5).

- The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has a jurisdiction that covers the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein. Unlike the FDA, the EMA evaluates drug submissions and provides non-binding scientific recommendations to the European Commission (EC). The EC then makes the final, legally binding decision on marketing authorization (4). This structural difference means that in Europe, marketing authorization is a two-stage process involving scientific assessment (EMA) followed by a legal-political decision (EC), which has implications for pan-European market strategy.

1.4. The Drive for Global Harmonization: The Role of the ICH

The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) is a crucial project established to standardize the technical aspects of drug registration. It brings together regulatory authorities from the United States, Europe, and Japan, along with experts from the pharmaceutical industry (3). The ICH produces guidance documents that define the accepted requirements for drug development. Among the most important for this field are ICH S7A and ICH S7B, which outline the specific requirements for conducting safety pharmacology studies (1, 8).

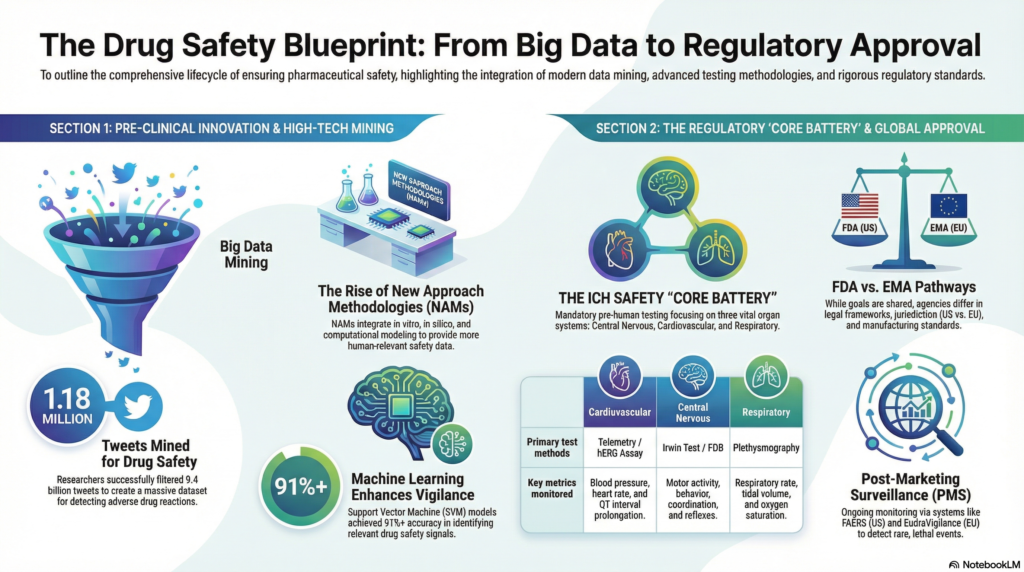

2. Pre-Approval Evaluation: The Safety Pharmacology Core Battery

This section details the mandatory safety testing required before an investigational new drug is administered to humans for the first time.

2.1. Objectives and Timing

The primary objective of safety pharmacology studies is to identify any undesirable pharmacodynamic properties of a substance that are relevant to human safety. These studies are specifically designed to protect volunteers in Phase I clinical trials from acute adverse effects (1, 6). A key regulatory mandate is that the “safety pharmacology core battery” of tests must be completed prior to the first administration of the drug in humans (1, 6).

2.2. The Core Battery Mandate (ICH S7A)

The ICH S7A guideline defines the “safety pharmacology core battery” as a set of studies that must investigate a drug’s effects on vital organ functions (1, 7). This core battery focuses on three critical physiological systems.

2.2.1. Central Nervous System (CNS)

The effects on the central nervous system must be assessed. This includes evaluations of motor activity, behavioral changes, coordination, and sensory/motor reflex responses. These assessments are typically conducted using standardized methodologies like a functional observational battery (FOB) or a modified Irwin test (1, 7).

2.2.2. Cardiovascular System

A thorough evaluation of the cardiovascular system is required, focusing on blood pressure, heart rate, and the electrocardiogram (ECG) (1, 7). A critical component of this assessment is the evaluation of delayed ventricular repolarization, often seen as QT interval prolongation on the ECG, due to its association with the risk of TdP (3, 6). The in vitro hERG assay, which measures a drug’s effect on a key potassium ion channel (IKr) critical for the repolarization phase of the cardiac action potential, plays a central role in this assessment (3, 8).

2.2.3. Respiratory System

The assessment of the respiratory system must include quantitative measurements of respiratory rate and other measures of function, such as tidal volume (1). The ICH S7A guideline explicitly states that simple clinical observation of animals is considered inadequate for this purpose. Instead, techniques like whole-body plethysmography are used to obtain precise data (1, 7).

2.3. Supplemental and Follow-Up Studies

If the results from the core battery, or the known properties of the drug, raise a cause for concern, follow-up studies are conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the potential risk. Furthermore, supplemental studies may be necessary to evaluate potential adverse effects on other organ systems not covered by the core battery, such as the renal/urinary and gastrointestinal systems (1).

2.4. Study Design and Conduct

As outlined in the ICH S7A guideline, safety pharmacology studies should adhere to several key design principles to ensure the data is reliable and relevant for regulatory review. Studies should:

- Define the dose-response relationship of any observed adverse effect (1).

- Preferably use unanesthetized, conscious animals. This avoids the confounding effects of anesthesia and provides more relevant data, often through the use of technologies like telemetry (1, 7).

- Be conducted in compliance with Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) standards. GLP ensures the generation of verifiable, high-quality data suitable for regulatory submission (1, 3).

3. Navigating the Drug Approval Labyrinth

The processes for gaining marketing authorization differ significantly between the United States and the European Union, offering distinct pathways for drug developers.

3.1. The U.S. FDA Approval Pathways

In the United States, the primary pathways for seeking marketing approval from the FDA are:

- New Drug Application (NDA): This is the standard pathway for small-molecule drugs (4).

- Biologic License Application (BLA): This pathway is used for biological products, which include monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and therapeutic proteins (4).

3.2. The EU EMA Approval Pathways

The European Union offers four different pathways for drug approval, providing flexibility based on the product and marketing strategy (4):

- Centralized Procedure: This is the mandatory pathway for all biologics, advanced therapy products, orphan drugs, and new medicines for major diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS. Approval via this route is valid in all EU member states.

- Mutual Recognition Procedure: This pathway is for medicinal products that have already received marketing authorization in at least one EU member state. The company can then seek recognition of that authorization in other EU countries.

- Decentralized Procedure: This is the most commonly used pathway and allows a company to apply for marketing authorization simultaneously in several EU member states for a product that has not yet been authorized in any EU country.

- National Procedure: This pathway is used when a sponsor wishes to market a drug in only a single member state.

3.3. Expedited Programs for Critical Drugs

To accelerate the availability of drugs for serious conditions that address an unmet medical need, the FDA offers several special programs:

- Fast Track: This designation is designed to facilitate the development and advance the review of drugs that treat serious conditions and fill an unmet medical need (5).

- Breakthrough Therapy: This designation expedites the development and review of drugs for which preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy (5).

- Accelerated Approval: This pathway allows for the approval of a drug based on its effect on a “surrogate endpoint” that is reasonably likely to predict a clinical benefit. The manufacturer is required to conduct post-marketing trials to confirm the clinical benefit, and the FDA may withdraw approval if these trials fail to do so (5).

- Priority Review: With a Priority Review designation, the FDA’s goal is to take action on an application within six months, compared to the standard ten months (5).

These designations illustrate a core principle of modern regulation: balancing the need for rigorous evidence against the urgent public health demand for novel therapies, a dynamic tension that shapes a drug’s entire development timeline.

4. Post-Marketing Surveillance: The Role of Pharmacovigilance

Regulatory approval is not an endpoint but the beginning of a drug’s life in a vast, uncontrolled patient population. This reality necessitates the robust pharmacovigilance systems required to monitor a drug’s performance and safety after it reaches the market.

4.1. Defining Pharmacovigilance

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines Pharmacovigilance as “the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug-related problem.” The primary aim of pharmacovigilance is to enhance patient care and safety related to the use of medicines and to support public health programs by providing reliable information for assessing the risk-benefit profile of medicines (9).

4.2. Traditional Surveillance Systems and Their Limitations

Traditional post-marketing surveillance relies on spontaneous reporting systems, such as the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), where healthcare providers and patients can report suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) (9). However, these systems have a major limitation: under-reporting. A systematic review of 37 studies established that it is estimated that over 90% of ADRs are not reported (9).

4.3. Risk Management Strategies: REMS vs. RMP

The FDA and EMA have distinct frameworks for managing known or potential risks associated with a medicine. The data gathered during the pre-approval phase, particularly from supplemental safety pharmacology studies, directly informs the initial Risk Management Plan (for EMA) or the potential need for a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (for FDA), linking pre-market investigation to post-market risk management.

| Feature | FDA REMS | EMA RMP |

| Applicability | Applies only to specific medicines with identified serious safety concerns. | Required for all new medicines, regardless of identified concerns. |

| Scope | Proposed strategies apply only to the specific identified risks. | Outlines the entire pharmacovigilance system and considers the overall safety profile. |

| Uniformity | Uniform across all U.S. territory. | Can be adjusted based on local legal requirements of member countries. |

4.4. Modern Innovations in Pharmacovigilance

To overcome the limitations of traditional surveillance, researchers are turning to modern technologies like social media and machine learning. In one study, researchers mined a publicly available dataset of over 9.4 billion tweets to create a massive corpus for identifying potential ADRs. By providing a large, validated list of tweet IDs for other researchers to access, this approach enables the creation of reusable datasets to train machine learning models, supplementing traditional pharmacovigilance efforts (9).

5. The Future of Regulatory Pharmacology

The field of regulatory pharmacology is continually evolving, with emerging methodologies and greater international cooperation shaping its future.

5.1. The Shift from Animal Models: New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) are a diverse suite of tools and technologies designed to evaluate drug safety without relying on animal testing, in line with the “3Rs” principles of Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement. These methods aim to provide more human-relevant data and include (10):

- In vitro models: These include cell-based assays, 3D organoids, and microengineered Organ-on-a-Chip systems that mimic organ-level functions.

- In silico models: These are computational approaches such as Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR), Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, and Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) to predict chemical properties and biological responses.

- In chemico methods: These techniques assess a compound’s reactivity directly, without biological systems. An example is the Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay (DPRA), which is used to test for skin sensitization potential.

While promising, the primary challenge for NAMs is regulatory acceptance, which requires extensive validation studies to demonstrate that these new methods are as, or more, predictive of human outcomes than the legacy animal models they aim to replace.

5.2. Evolving Cardiovascular Safety Assessment: The CiPA Initiative

The Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA) is a novel paradigm being advanced by regulatory agencies like the FDA. It aims to provide a more accurate and mechanistic assessment of a drug’s potential to cause cardiac arrhythmias. CiPA moves beyond the simple reliance on the hERG assay and QT prolongation data by integrating data from multiple in vitro ion channel assays with in silico reconstructions of cardiac electrophysiological activity. This initiative represents the direct scientific successor to the initial regulatory response following the terfenadine case, shifting from a broad observational approach to a sophisticated, mechanistic-based prediction of proarrhythmic risk, thereby reducing the number of potentially valuable drugs that are unnecessarily terminated during development (6).

5.3. Deepening International Collaboration

There is a growing trend of cooperation between the EMA and FDA to streamline regulatory processes. A significant milestone was the 2017 mutual recognition agreement (MRA), which allows the agencies to rely on each other’s Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) inspections. This collaboration makes the drug registration process more efficient and less expensive for the pharmaceutical industry by reducing duplicative inspections (4).

Conclusion

Regulatory pharmacology plays an indispensable role in safeguarding public health by ensuring that medicines are safe, effective, and of high quality. From its historical origins in response to tragic safety events to its current state as a data-driven, globally harmonized discipline, the field is central to the entire drug lifecycle. As it continues to evolve, regulatory pharmacology is embracing scientific and technological advancements, including New Approach Methodologies that reduce reliance on animal testing and AI-driven tools that enhance post-marketing surveillance. This commitment to innovation, coupled with a drive for deeper international collaboration, ensures that the field is well-positioned to meet the challenges of modern medicine and continue its vital mission of protecting patients worldwide.

References

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline S7A: Safety Pharmacology Studies for Human Pharmaceuticals. 8 November 2000.

- Safety pharmacology [Internet]. Wikipedia; 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 26]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Safety_pharmacology

- Pugsley MK, Authier S, Curtis MJ. Principles of Safety Pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(7):1382–99.

- Tuszyner A. Similar but not the same: an in-depth look at the differences between EMA and FDA [Internet]. Mabion; 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 26]. Available from: https://mabion.eu/similar-but-not-the-same-an-in-depth-look-at-the-differences-between-ema-and-fda/

- Food and Drug Administration. Development & Approval Process | Drugs [Internet]. FDA; 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs

- Safety pharmacology [Internet]. Wikipedia; 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 26]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Safety_pharmacology

- Safety pharmacology – Core Battery of studies- ICH S7A/S7B [Internet]. Vivotecnia; [cited 2024 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.vivotecnia.com/pharmacology/safety-pharmacology/

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH S7B: Nonclinical evaluation of the potential for delayed ventricular repolarization (QT interval prolongation) by human pharmaceuticals.

- Tekumalla R, Banda JM. A large-scale Twitter dataset for drug safety applications mined from publicly existing resources. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.02986. 2019 Nov 7.

- New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): The Future of Toxicology and Safety Testing [Internet]. 2024 Jul 23 [cited 2024 Oct 26]. Available from: https://example-company.com/blog/new-approach-methodologies-nams-the-future-of-toxicology-and-safety-testing/

Medical Disclaimer

The medical information on this post is for general educational purposes only and is provided by Pharmacology Mentor. While we strive to keep content current and accurate, Pharmacology Mentor makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the post, the website, or any information, products, services, or related graphics for any purpose. This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment; always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition and never disregard or delay seeking professional advice because of something you have read here. Reliance on any information provided is solely at your own risk.