1. Introduction/Overview

The field of pharmacology has traditionally concerned itself with the actions of exogenous small molecules and biologics on physiological systems. Gene therapy represents a paradigm shift, wherein the therapeutic agent is nucleic acid material designed to modify the expression of a patient’s genes or to correct genetic defects. This approach moves treatment from the protein or receptor level to the fundamental genetic code, offering potential cures for monogenic disorders and novel strategies for complex diseases. The discipline requires an integration of molecular biology, virology, immunology, and classical pharmacokinetic principles.

The clinical relevance of gene therapy has transitioned from theoretical promise to tangible reality, with multiple regulatory approvals across North America, Europe, and Asia. These therapies address conditions with high unmet medical need, including inherited retinal dystrophies, spinal muscular atrophy, hematological malignancies, and certain metabolic disorders. The therapeutic importance lies not only in the potential for durable or curative responses from a single administration but also in the ability to target diseases previously considered untreatable at their root cause. The associated costs, logistical challenges, and unique safety profiles necessitate a deep pharmacological understanding from clinicians and pharmacists.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate the major classes of gene therapy agents, including viral vectors, non-viral vectors, and genome editing platforms, based on their structural and functional characteristics.

- Explain the detailed molecular mechanisms by which gene therapy agents achieve therapeutic gene addition, silencing, or correction, including processes from cellular entry to genomic integration or episomal persistence.

- Analyze the unique pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of gene therapies, focusing on biodistribution, long-term expression, and the relationship between vector administration and clinical effect.

- Evaluate the approved clinical applications, significant adverse effect profiles, and major drug interaction potentials for currently available gene therapy products.

- Apply knowledge of special considerations, including immunogenicity, insertional mutagenesis risk, and requirements for patient monitoring, to the safe clinical use of gene therapies.

2. Classification

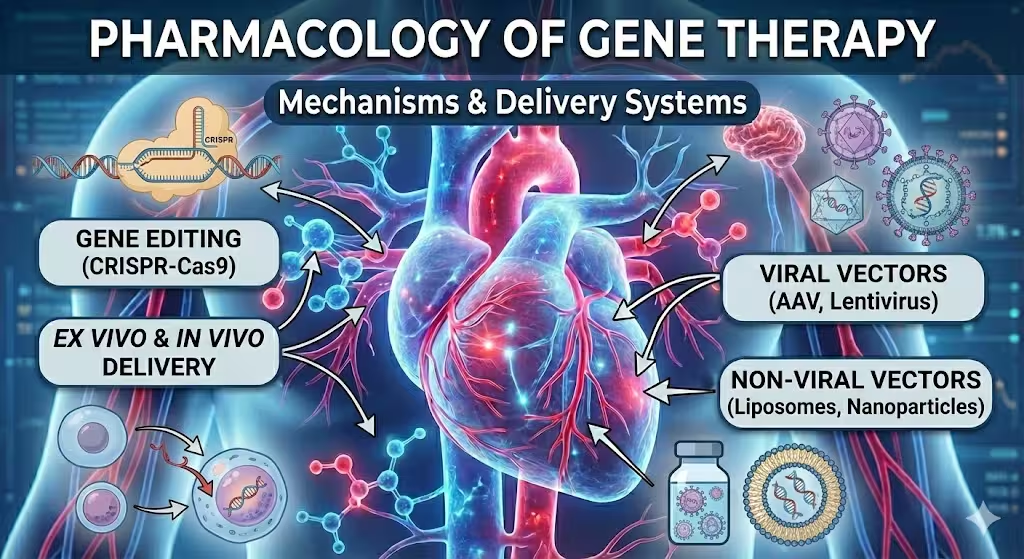

Gene therapy agents are classified not by a common chemical structure but by their functional components and delivery mechanisms. The primary classification is based on the vector system used to deliver the therapeutic genetic material.

Viral Vectors

Viruses are engineered to serve as delivery vehicles, having had their pathogenic genes removed and replaced with therapeutic transgenes. Their classification follows the viral family of origin.

- Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors: Small, non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA viruses. They are replication-deficient and generally non-pathogenic. Different serotypes (e.g., AAV2, AAV5, AAV8, AAV9) exhibit distinct tropisms for tissues such as liver, skeletal muscle, central nervous system, and retina. They predominantly exist as non-integrating episomes in the host cell nucleus, leading to long-term expression in non-dividing cells.

- Lentiviral Vectors: Derived from HIV-1 and other lentiviruses. They are enveloped, single-stranded RNA retroviruses. Their key pharmacological feature is the ability to integrate their genetic cargo into the host genome of both dividing and non-dividing cells, enabling permanent genetic modification of the target cell and its progeny. This is central to ex vivo therapies, such as CAR-T cell engineering.

- Retroviral Vectors (Gamma-Retroviral): Derived from murine leukemia virus (MLV). Similar to lentiviruses, they integrate into the host genome but require target cell division for nuclear entry and integration. Their use has diminished relative to lentiviral vectors due to a higher observed risk of insertional oncogenesis.

- Adenoviral Vectors: Non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses with high transduction efficiency across many cell types. They remain episomal but can elicit strong innate and adaptive immune responses, which historically limited their use to applications where transient, high-level expression is desired, such as in some vaccine platforms or oncolytic therapies.

Non-Viral Vectors and Nucleic Acid Platforms

This category encompasses physical and chemical methods for nucleic acid delivery, often aiming to improve safety by avoiding viral components.

- Naked Plasmid DNA: Circular DNA molecules containing the therapeutic expression cassette. Delivery is inefficient and typically requires physical methods (e.g., electroporation, hydrodynamic injection) for clinical relevance.

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Synthetic, spherical vesicles composed of ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids. They encapsulate and protect nucleic acids (mRNA, siRNA, DNA) and facilitate cellular uptake through endocytosis. LNPs were pivotal for mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines and are used in siRNA therapies like patisiran.

- Polymer-Based Vectors: Cationic polymers (e.g., polyethylenimine, PEI) that condense nucleic acids into polyplexes via electrostatic interactions.

- Genome Editing Platforms: These are not vectors per se but enzymatic systems delivered as nucleic acids (mRNA, plasmid DNA) or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. The primary systems are:

- CRISPR-Cas Systems: Utilize a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct a Cas nuclease (e.g., Cas9, Cas12a) to a specific genomic locus for double-strand break induction, enabling gene knockout or precise editing via homology-directed repair (HDR).

- Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs): Earlier generation engineered protein systems that also create targeted double-strand breaks.

- Base Editors and Prime Editors: Derived from CRISPR systems, these allow for direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another (base editors) or templated insertion of small sequences (prime editors) without creating a double-strand break, potentially improving safety.

Therapeutic Genetic Material

The payload carried by the vector constitutes another layer of classification.

- Gene Addition: Delivery of a functional copy of a gene to compensate for a defective or deficient endogenous gene (e.g., RPEG5 in voretigene neparvovec).

- Gene Silencing: Delivery of sequences like siRNA, shRNA, or antisense oligonucleotides to inhibit the expression of a specific gene (e.g., transthyretin in patisiran).

- Gene Editing: Direct modification of the endogenous genomic sequence to correct a mutation, disrupt a gene, or insert a new sequence.

- Gene Regulation: Use of engineered transcription factors or on/off switches to control endogenous gene expression.

3. Mechanism of Action

The pharmacodynamic action of a gene therapy is a multi-step process, beginning with delivery to the target tissue and culminating in a sustained biological effect. The mechanism is fundamentally distinct from traditional receptor-ligand interactions.

Cellular Entry and Trafficking

The initial step involves binding to cell surface receptors, which is highly vector-specific. AAV vectors, for instance, bind primarily to primary receptors like heparan sulfate proteoglycan (AAV2) and secondary co-receptors (e.g., αVβ5 integrin, FGFR1) for internalization. Lentiviral vectors engage receptors such as the low-density lipoprotein receptor or require pseudotyping with vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G) protein for broad tropism. Following receptor-mediated endocytosis, the vector must escape the endosomal compartment. AAV vectors use pH-dependent conformational changes, while LNPs rely on the ionizable lipid becoming positively charged in the acidic endosome, disrupting the endosomal membrane. The therapeutic cargo is then trafficked to the nucleus.

Nuclear Entry and Transgene Processing

For viral vectors, the capsid must navigate the nuclear pore complex. AAV capsids are small enough for passive entry, while lentiviral pre-integration complexes contain nuclear localization signals for active transport. Once inside the nucleus, the genetic payload is uncoated. For AAV, the single-stranded DNA genome is converted to double-stranded DNA, a rate-limiting step that can be bypassed by using self-complementary AAV (scAAV) vectors. The double-stranded DNA then exists as a circular episome. For lentiviral vectors, the viral RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into double-stranded DNA within the cytoplasm prior to nuclear import.

Transgene Expression and Persistence

The expression cassette, containing a promoter, the therapeutic transgene, and a polyadenylation signal, is transcribed by host cell RNA polymerase II. The resulting mRNA is exported, translated, and the therapeutic protein is produced. The duration of expression is dictated by the vector’s fate. Episomal AAV genomes can persist for years in post-mitotic cells (e.g., neurons, photoreceptors, cardiomyocytes), but are diluted in dividing cell populations. Integrated lentiviral and retroviral vectors provide a permanent genetic change, ensuring expression in all daughter cells, which is critical for hematopoietic stem cell therapies.

Mechanisms of Genome Editing

The mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 systems exemplifies gene editing pharmacology. The delivered gRNA-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex or the encoding nucleic acids assemble in the cell. The gRNA directs Cas9 to a complementary genomic locus adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). Cas9 induces a double-strand break (DSB). The cell repairs this DSB via one of two primary pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. This can disrupt the reading frame of a gene, leading to knockout of a deleterious gene (e.g., CCR5 in HIV resistance).

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a donor DNA template (supplied with the therapy) to copy sequence information into the break site. This allows for correction of point mutations or insertion of whole genes.

Base editors fuse a catalytically impaired Cas protein to a deaminase enzyme, which directly converts, for example, a C•G base pair to a T•A pair without creating a DSB, offering a potentially safer correction strategy for single-nucleotide variants.

4. Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of gene therapies are unconventional, characterized by a single, often irreversible, administration leading to a prolonged pharmacodynamic response. The classic ADME model is applied differently, focusing on vector biodistribution, transduction efficiency, and transgene expression kinetics rather than repeated systemic exposure.

Absorption

Systemic absorption is not typically relevant, as most gene therapies are administered via direct routes: intravenous infusion, intrathecal injection, intravitreal injection, or direct injection into a tissue (e.g., skeletal muscle, liver, tumor). For systemically administered vectors (e.g., IV AAV), absorption from the administration site is complete but is immediately followed by complex distribution dynamics. Local administration aims to maximize target tissue exposure while minimizing systemic distribution and off-target effects.

Distribution

Biodistribution is a critical and highly variable pharmacokinetic parameter. Following intravenous administration, viral vectors and LNPs are rapidly distributed, but their tropism determines final localization. AAV9, for example, crosses the blood-brain barrier efficiently, making it suitable for CNS disorders, while AAV8 has high hepatic tropism. Distribution is influenced by vector dose, serotype, presence of neutralizing antibodies, and host factors like receptor density. Vector genomes can be detected in non-target tissues, including the liver, spleen, and gonads, which has implications for toxicity. Ex vivo therapies, where cells are modified outside the body and reinfused, have a distribution profile dictated by the homing and engraftment of the modified cells, typically to bone marrow or tumor sites.

Metabolism and Elimination

Gene therapy vectors are not metabolized by cytochrome P450 systems. Their fate is primarily determined by immune-mediated clearance and cellular turnover.

- Pre-existing Immunity: Neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against viral capsids (e.g., from prior wild-type AAV exposure) can opsonize vectors, leading to rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) before reaching target cells, rendering treatment ineffective. This necessitates patient screening prior to therapy.

- Innate Immune Recognition: Vector components (viral capsids, bacterial DNA sequences in plasmids, double-stranded RNA intermediates) can be recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors, triggering inflammatory cytokine release and accelerating clearance.

- Cell-Mediated Clearance: Transduced cells expressing viral or novel transgenic proteins may be eliminated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), potentially abrogating therapeutic benefit. This is a recognized challenge with AAV therapies.

- Physical Degradation: Non-integrated DNA episomes and mRNA are subject to eventual degradation by cellular nucleases. The half-life of episomal AAV genomes in terminally differentiated cells, however, can be measured in years.

Excretion of intact vectors is minimal. Degraded components (nucleotides, lipids, proteins) are processed through standard catabolic and excretory pathways.

Half-life and Dosing Considerations

The plasma half-life of the vector particle itself is typically short, ranging from minutes to a few hours. The critical pharmacokinetic metric is the duration of transgene expression, which functions as the effective “half-life” of the pharmacological effect. This can be lifelong for integrated therapies or persist for many years for AAV-based therapies in non-dividing cells. Consequently, dosing is almost always a single administration. The dose is expressed as vector genomes per kilogram of body weight (vg/kg) for viral vectors or total milligrams of nucleic acid for non-viral therapies. Dose-ranging is critical, as there is often a narrow therapeutic window between efficacy and toxicity (e.g., liver inflammation, immune responses). Re-dosing is generally not feasible due to the development of high-titer neutralizing antibodies against the vector.

5. Therapeutic Uses/Clinical Applications

Gene therapy has moved from experimental trials to standard of care for several severe conditions. Approved applications largely target monogenic disorders with well-defined pathophysiology.

Approved Indications

- Ophthalmic Disorders:

- Voretigene Neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2): For biallelic RPE65 mutation-associated retinal dystrophy. Delivers a functional copy of the RPE65 gene to retinal pigment epithelium cells via subretinal injection, restoring the visual cycle.

- Neuromuscular Disorders:

- Onasemnogene Abeparvovec (AAV9-SMN1): For spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) with bi-allelic mutations in SMN1. Systemically delivered AAV9 carries a functional SMN1 transgene to motor neurons, dramatically improving motor function and survival.

- Elevidys (Delandistrogene Moxeparvovec, AAVrh74-MHCK7-micro-dystrophin): For Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) with a confirmed mutation in the DMD gene. Delivers a truncated, functional micro-dystrophin gene to skeletal and cardiac muscle.

- Hematological Disorders:

- Ex Vivo Lentiviral Therapies: Autologous CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells are genetically modified ex vivo to express a functional gene before reinfusion.

- Betibeglogene Autotemcel (β-A-T): For transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. Uses a lentiviral vector to introduce a functional β-globin gene variant.

- Eliglustat (not gene therapy) and similar investigational approaches for lysosomal storage diseases like metachromatic leukodystrophy and adrenoleukodystrophy.

- Ex Vivo Lentiviral Therapies: Autologous CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells are genetically modified ex vivo to express a functional gene before reinfusion.

- Oncology:

- CAR-T Cell Therapies (e.g., Tisagenlecleucel, Axicabtagene Ciloleucel): Although often categorized separately, these are ex vivo gene therapies. Patient T cells are engineered with a lentiviral or retroviral vector to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) targeting a tumor antigen (e.g., CD19). Upon reinfusion, these cells proliferate and mediate tumor cell killing.

- Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC): An oncolytic viral therapy (modified herpes simplex virus) for melanoma, which includes a GM-CSF transgene to stimulate anti-tumor immunity.

- Hereditary Transthyretin-Mediated (hATTR) Amyloidosis:

- Patisiran: An LNP-formulated siRNA that silences the transthyretin (TTR) gene in hepatocytes via RNA interference, reducing production of amyloidogenic protein. It represents a non-viral gene-silencing approach.

- Inotersen: An antisense oligonucleotide with a similar mechanism, administered subcutaneously.

Off-Label and Investigational Uses

While formal off-label use is limited due to product-specificity and cost, clinical research is extensive. Investigational areas include hemophilia A and B (AAV-mediated Factor VIII or IX expression), sickle cell disease (using gene editing to reactivate fetal hemoglobin or correct the HBB mutation), Huntington’s disease (gene silencing), cystic fibrosis, and various forms of inherited blindness and deafness. Cardiovascular applications, such as AAV-mediated expression of SERCA2a for heart failure, have been explored but with mixed clinical outcomes to date.

6. Adverse Effects

The adverse effect profile of gene therapies is intimately linked to the vector, route of administration, transgene product, and immune response. Effects can be acute, related to vector infusion, or delayed, related to transgene expression or genomic alteration.

Common Side Effects

- Acute Infusion Reactions: Fever, chills, hypotension, nausea, and fatigue are common with systemic intravenous administration of viral vectors and LNPs, driven by cytokine release (e.g., interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α).

- Elevated Liver Enzymes: A frequent and expected finding with systemically administered AAV therapies. This reflects hepatocyte transduction and a subsequent adaptive immune response against transduced hepatocytes, necessitating prophylactic or reactive corticosteroid regimens.

- Local Reactions: Pain, inflammation, and edema at the site of local injection (intrathecal, intramuscular, intravitreal).

- Flu-like Symptoms: Myalgia, arthralgia, and headache.

Serious/Rare Adverse Reactions

- Thrombotic Microangiopathy (TMA) and Complement Activation: Observed with some high-dose systemic AAV therapies, potentially related to direct vector interaction with platelets and complement proteins. This can manifest as thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and acute kidney injury.

- Cardiotoxicity: Myocarditis and elevated troponin levels have been reported, particularly with high-dose AAV therapies, possibly due to direct cardiomyocyte transduction and immune-mediated damage.

- Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) and Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS): These are hallmark toxicities of CAR-T cell therapies, caused by massive T-cell activation and proliferation, leading to high fever, hypotension, capillary leak, and in severe cases, neurologic symptoms like confusion, aphasia, and seizures. Management involves anti-IL-6 therapy (tocilizumab) and corticosteroids.

- Insertional Mutagenesis and Oncogenesis: A long-term risk associated with integrating vectors (gamma-retroviral, lentiviral). If the vector integrates near a proto-oncogene, it can dysregulate its expression, potentially leading to clonal expansion and leukemia. This risk appears lower with modern lentiviral vectors and self-inactivating (SIN) designs but remains a theoretical concern requiring long-term patient monitoring.

- Germline Transmission Risk: The theoretical risk that vector DNA could integrate into germ cells (sperm or oocytes) and be passed to offspring. While no human cases have been reported, it is a standard parameter assessed in preclinical studies.

- Off-Target Genome Editing: For CRISPR-based therapies, the gRNA may bind to and cleave genomic sites with sequence homology to the intended target, leading to unintended mutations. The frequency and clinical significance of these events are areas of active investigation.

Black Box Warnings

Several gene therapies carry black box warnings, the strongest FDA-mandated safety alert.

- Onasemnogene Abeparvovec: Contains warnings for acute serious liver injury and acute liver failure, requiring monitoring of liver function before and after infusion.

- CAR-T Cell Therapies (e.g., Tisagenlecleucel): Carry black box warnings for CRS and neurologic toxicities, which can be life-threatening.

- Betibeglogene Autotemcel: Includes a warning for the potential risk of hematologic malignancy, reflecting the insertional mutagenesis concern.

7. Drug Interactions

Drug interactions for gene therapies differ from small molecule interactions, as they are less about metabolic enzyme competition and more about immunological and physiological modulation.

Major Drug-Drug Interactions

- Immunosuppressive Agents: Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) are routinely used prophylactically or therapeutically to mitigate immune responses against the vector or transduced cells. Other immunosuppressants like mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus may be used in certain protocols. Concurrent use of broad immunosuppression could theoretically increase the risk of opportunistic infections.

- Vaccinations: Live attenuated vaccines are generally contraindicated in patients receiving concurrent immunosuppressive regimens for gene therapy. Furthermore, administration of vaccines containing viral components (e.g., adenovirus-based vaccines) could potentially induce or boost neutralizing antibodies that might cross-react with gene therapy vectors, impacting future efficacy.

- Anticoagulants/Antiplatelets: Given the risk of thrombotic microangiopathy with some systemic AAV therapies, concomitant use of these agents requires careful monitoring of coagulation parameters.

- Myelosuppressive Chemotherapy: For ex vivo therapies involving hematopoietic stem cells (e.g., for β-thalassemia), patients undergo myeloablative conditioning (e.g., with busulfan) prior to reinfusion of modified cells. This conditioning regimen has its own significant toxicity profile and drug interactions.

Contraindications

Contraindications are often specific to individual products but share common themes.

- Pre-existing High-Titer Neutralizing Antibodies: A near-universal contraindication for systemically administered viral vector therapies. Patients are screened for anti-capsid antibodies, and those with titers above a predefined threshold are excluded from treatment.

- Active Infection or Uncontrolled Malignancy: Due to the associated immune activation and, in some cases, required immunosuppression.

- Severe Hepatic Impairment: For therapies with known hepatotoxicity (e.g., onasemnogene abeparvovec) or those metabolized/excreted hepatically (e.g., LNP components).

- Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Almost universally contraindicated due to lack of safety data and theoretical risks to the fetus or infant.

- Specific Genetic Mutations: Some therapies are only approved for patients with specific mutations (e.g., certain SMN1 deletions for SMA therapy), and their use in patients with other mutations may be contraindicated or ineffective.

8. Special Considerations

Use in Pregnancy and Lactation

Gene therapies are contraindicated during pregnancy. The potential risks to the fetus include direct teratogenic effects of the vector or conditioning chemotherapy, the theoretical risk of germline integration, and the consequences of maternal immune or inflammatory responses. Animal reproduction studies are typically lacking. For women of childbearing potential, a negative pregnancy test is required prior to treatment initiation, and effective contraception is mandated for a specified period (often 6-12 months or more) following therapy. Data regarding excretion in human milk are not available, and breastfeeding is not recommended due to the potential for serious adverse reactions in the infant.

Pediatric Considerations

Many approved gene therapies are specifically for pediatric-onset genetic diseases (e.g., SMA, DMD, retinal dystrophy). Dosing is almost always weight-based (vg/kg). Special attention is required for the management of infusion reactions and toxicities in young children. Long-term monitoring for delayed adverse effects, such as insertional oncogenesis or impact on growth and development, is essential. The immune system in very young infants may be less likely to have pre-existing neutralizing antibodies, potentially improving transduction efficiency.

Geriatric Considerations

Formal clinical data in elderly populations are often limited. Age-related decline in immune function (immunosenescence) could theoretically alter both the efficacy (reduced immune clearance of vector) and toxicity (altered inflammatory response) profiles. Comorbid conditions common in older adults, such as renal or hepatic impairment, cardiovascular disease, and polypharmacy, must be carefully evaluated in the risk-benefit assessment.

Renal and Hepatic Impairment

Hepatic Impairment is a critical consideration. The liver is a primary site of vector sequestration and transgene expression for many systemic therapies. Pre-existing liver disease may exacerbate drug-induced hepatotoxicity, alter vector biodistribution, and impact the metabolism of concomitant medications (e.g., immunosuppressants). Dose adjustments in hepatic impairment are not standardized and are often a contraindication. Renal Impairment is less frequently a primary concern for the vector itself, but may be relevant due to acute kidney injury from conditions like thrombotic microangiopathy or as a comorbidity affecting overall patient fitness for treatment. The excipients and degradation products of LNPs are cleared hepatically, not renally.

9. Summary/Key Points

- Gene therapy pharmacology involves the delivery of nucleic acids as drugs to modify gene expression, offering potential cures for genetic disorders through mechanisms of gene addition, silencing, or editing.

- Agents are classified primarily by delivery vector: viral (AAV, lentiviral, adenoviral) and non-viral (LNPs, polymers, naked DNA), each with distinct tropisms, persistence profiles, and immunogenicities.

- The mechanism of action is multi-step, involving cellular binding, internalization, nuclear trafficking, and ultimately sustained production of a therapeutic protein or permanent genomic alteration, as seen with CRISPR-Cas systems.

- Pharmacokinetics are unique, characterized by single-dose administration, complex biodistribution determined by vector tropism, and a prolonged duration of effect measured in years, with clearance dominated by immune mechanisms.

- Clinical applications are established for monogenic retinal, neuromuscular, hematological, and oncologic disorders, with a rapidly expanding pipeline for other conditions.

- Adverse effects include acute infusion reactions, hepatotoxicity, thrombotic microangiopathy, and serious immune-mediated syndromes like CRS and ICANS. Long-term risks include insertional mutagenesis and off-target genome editing.

- Major drug interactions involve immunosuppressive regimens and vaccinations, while key contraindications include pre-existing neutralizing antibodies and active infections.

- Special considerations necessitate avoidance in pregnancy, careful pediatric monitoring, and cautious use in patients with hepatic impairment due to the central role of the liver in vector processing.

Clinical Pearls

- Patient selection is paramount; screening for pre-existing anti-vector antibodies is a standard prerequisite for most viral vector therapies.

- The management of gene therapy toxicities, particularly hepatotoxicity and CRS, is proactive and protocol-driven, often involving corticosteroids and cytokine blockade.

- The single-administration, potentially curative nature of these therapies creates unique challenges in benefit-risk assessment, long-term follow-up, and health economic evaluation.

- Understanding the specific vector and transgene is essential for anticipating the timing, nature, and management of both therapeutic effects and adverse events.

References

- Whalen K, Finkel R, Panavelil TA. Lippincott Illustrated Reviews: Pharmacology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

- Rang HP, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G. Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology. 9th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2020.

- Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann BC. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 14th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2023.

- Golan DE, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW. Principles of Pharmacology: The Pathophysiologic Basis of Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Katzung BG, Vanderah TW. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2021.

- Trevor AJ, Katzung BG, Kruidering-Hall M. Katzung & Trevor’s Pharmacology: Examination & Board Review. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2022.

- Rang HP, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G. Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology. 9th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2020.

- Whalen K, Finkel R, Panavelil TA. Lippincott Illustrated Reviews: Pharmacology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

⚠️ Medical Disclaimer

This article is intended for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

The information provided here is based on current scientific literature and established pharmacological principles. However, medical knowledge evolves continuously, and individual patient responses to medications may vary. Healthcare professionals should always use their clinical judgment when applying this information to patient care.

Medical Disclaimer

The medical information on this post is for general educational purposes only and is provided by Pharmacology Mentor. While we strive to keep content current and accurate, Pharmacology Mentor makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the post, the website, or any information, products, services, or related graphics for any purpose. This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment; always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition and never disregard or delay seeking professional advice because of something you have read here. Reliance on any information provided is solely at your own risk.